Out of billions of stars in the Milky Way galaxy, there’s one in particular, orbiting 25,000 light-years from the galactic core, that affects Earth day by day, moment by moment. That star, of course, is the sun. While the sun’s activity cycle has been tracked for about two and a half centuries, the use of space-based telescopes offers a new and unique perspective of our nearest star.

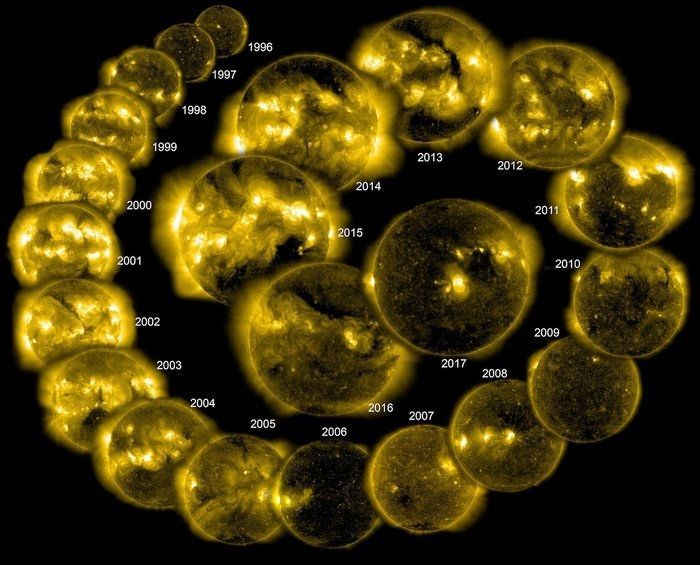

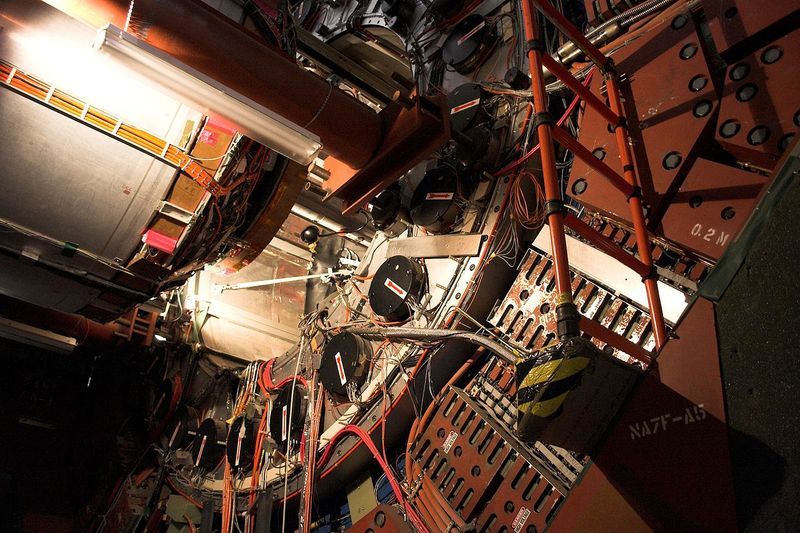

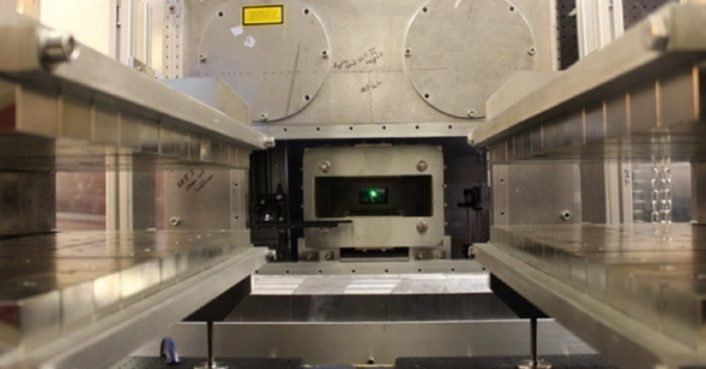

The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA), has been in space for more than 22 years — the average length of one completed solar magnetic cycle, according to an image caption from ESA. In the new image, SOHO researchers pulled together 22 images of the sun, taken each spring over the course of a full solar cycle. When the sun is at its most active, strong magnetic fields show up as bright spots in the sun’s outer atmosphere, called the corona; black sunspots appear as concentrations of magnetic fields reduce the sun’s surface temperature during active periods as well.

Throughout the sun’s magnetic cycles, the polarity of the sun’s magnetic field gradually flips. This initial phase takes 11 years, and after another 11 years, the magnetic field’s orientation returns to where it began. Monitoring the entire 22-year cycle provided significant data regarding the interaction between the sun’s activity and Earth, improved space-weather forecasting capabilities and more, ESA officials said in the caption. SOHO has revealed much about the sun itself, capturing “sunquakes,” discovering waves traveling through the corona and collecting details about the charged particles it propels into space, called the solar wind.