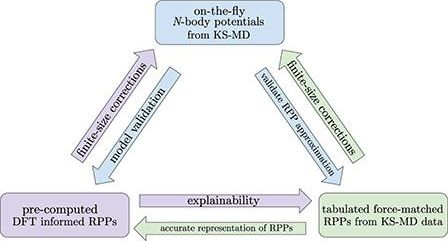

In this work, we carry out KS-MD simulations for a range of elements, temperatures, and densities, allowing for a systematic comparison of three RPP models. While multiple RPP models can be selected, 7–11 7. J. Vorberger and D. Gericke, “Effective ion–ion potentials in warm dense matter,” High Energy Density Phys. 9, 178 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hedp.2012.12.009 8. Y. Hou, J. Dai, D. Kang, W. Ma, and J. Yuan, “Equations of state and transport properties of mixtures in the warm dense regime,” Phys. Plasmas 22, 022711 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4913424 9. K. Wünsch, J. Vorberger, and D. Gericke, “Ion structure in warm dense matter: Benchmarking solutions of hypernetted-chain equations by first-principle simulations,” Phys. Rev. E 79, 010201 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.79.010201 10. L. Stanton and M. Murillo, “Unified description of linear screening in dense plasmas,” Phys. Rev. E 91, 033104 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.91.033104 11. W. Wilson, L. Haggmark, and J. Biersack, “Calculations of nuclear stopping, ranges, and straggling in the low-energy region,” Phys. Rev. B 15, 2458 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.15.2458 we choose to compare the widely used Yukawa potential, which accounts for screening by linearly perturbing around a uniform density in the long-wavelength (Thomas–Fermi) limit, a potential constructed from a neutral pseudo-atom (NPA) approach, 12–15 12. L. Harbour, M. Dharma-wardana, D. D. Klug, and L. J. Lewis, “Pair potentials for warm dense matter and their application to x-ray Thomson scattering in aluminum and beryllium,” Phys. Rev. E 94, 053211 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.94.053211 13. M. Dharma-wardana, “Electron-ion and ion-ion potentials for modeling warm dense matter: Applications to laser-heated or shock-compressed Al and Si,” Phys. Rev. E 86, 036407 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.86.036407 14. F. Perrot and M. Dharma-Wardana, “Equation of state and transport properties of an interacting multispecies plasma: Application to a multiply ionized al plasma,” Phys. Rev. E 52, 5352 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.52.5352 15. L. Harbour, G. Förster, M. Dharma-wardana, and L. J. Lewis, “Ion-ion dynamic structure factor, acoustic modes, and equation of state of two-temperature warm dense aluminum,” Phys. Rev. E 97, 043210 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.97.043210 and the optimal force-matched RPP that is constructed directly from KS-MD simulation data.

Each of the models we chose impacts our physics understanding and has clear computational consequences. For example, success of the Yukawa model reveals the insensitivity to choices in the pseudopotential and screening function and allows for the largest-scale simulations. Large improvements are expected from the NPA model, which makes many fewer assumptions with a modest cost of pre-computing and tabulating forces. (See the Appendix for more details on the NPA model.) The force-matched RPP requires KS-MD data and is therefore the most expensive to produce, but it reveals the limitations of RPPs themselves since they are by definition the optimal RPP.

Using multiple metrics of comparison between RPP-MD and KS-MD including the relative force error, ion–ion equilibrium radial distribution function g (r), Einstein frequency, power spectrum, and the self-diffusion transport coefficient, the accuracy of each RPP model is analyzed. By simulating disparate elements, namely, an alkali metal, multiple transition metals, a halogen, a nonmetal, and a noble gas, we see that force-matched RPPs are valid for simulating dense plasmas at temperatures above fractions of an eV and beyond. We find that for all cases except for low temperature carbon, force-matched RPPs accurately describe the results obtained from KS-MD to within a few percent. By contrast, the Yukawa model appears to systematically fail at describing results from KS-MD at low temperatures for the conditions studied here validating the need for alternate models such as force-matching and NPA approaches at these conditions.