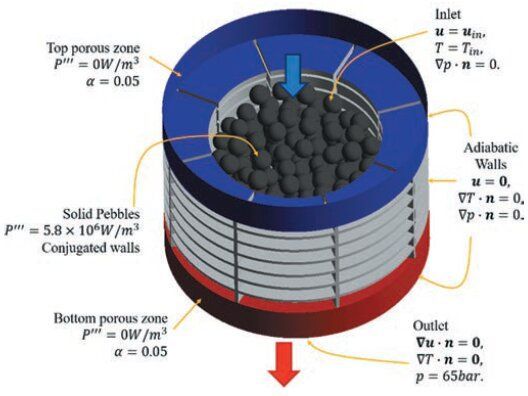

The BREST-OD-300 reactor is planned to start operating in 2026. A fuel production facility will be built by 2023 and the construction of an irradiated fuel reprocessing module is scheduled to start by 2024, Rosatom said. The design of the lead-cooled reactor is based on the principles of so-called natural safety, which makes it possible to abandon the melt trap.

“The successful implementation of this project will allow our country to become the world’s first owner of the nuclear power technology which fully meets the principles of sustainable development in terms of environment, accessibility, reliability, and efficient use of resources,” said Rosatom’s Director General Alexey Likhachev. “Today, we reaffirm our reputation as a leader in world progress in the nuclear technologies, that offers humanity unique solutions aimed at improving people’s lives,” he added.

According to President of the Kurchatov Institute Mikhail Kovalchuk, the project is aimed at bringing nuclear power to a new level.