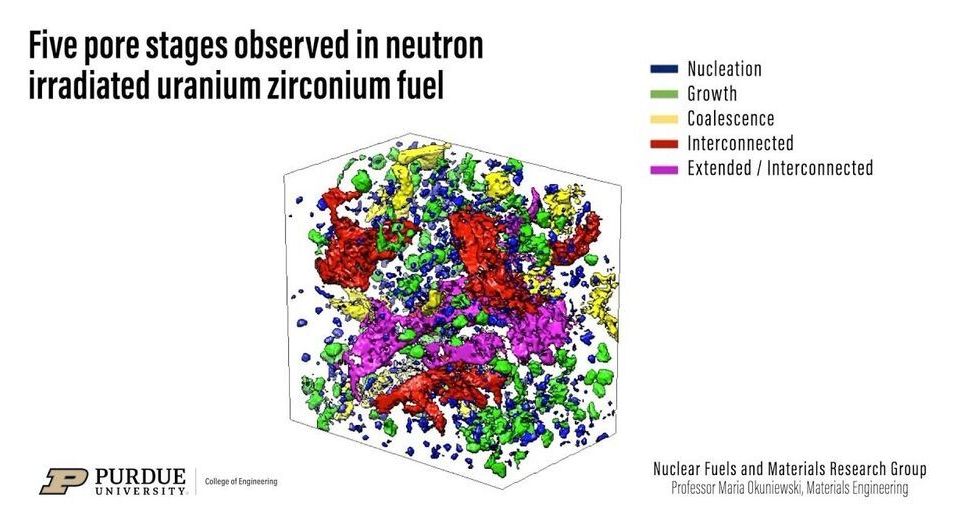

In a feat requiring perseverance, world-leading technology, and no small amount of caution, scientists have used intense X-rays to inspect irradiated nuclear fuel. The imaging, led by researchers at Purdue University and conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory, revealed a 3D view of the fuel’s interior structure, laying the groundwork for better nuclear fuel designs and models.

Until now, examinations of uranium fuel have been limited to mostly surface microscopy or to various characterization techniques using mock versions that possess little radioactivity. But scientists want to know at a deeper level how the material changes as it undergoes fission inside a nuclear reactor. The resulting insights from this study, which the Journal of Nuclear Materials published in August 2020, can lead to nuclear fuels that function more efficiently and cost less to develop.

To get an interior view of the uranium-zirconium fuel studied, the researchers sectioned off a bit of used fuel small enough to be handled safely—a capability developed only within the last seven years. Then, to see inside this tiny metallic sample, they turned to the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Argonne.