Circa 2014

French director, Luc Besson, talks to GQ ahead of the UK release of action-thriller Lucy.

A group of monkeys were found to have “human-like” brain development, including faster reactions and better memories, after a joint Sino-American team of researchers spliced a human gene into their genetic makeup.

Researchers from the Kunming Institute of Zoology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), and the University of North Carolina in the United States modified the genes of 11 monkeys (eight first-generation and three second-generation) with the addition of copies of the human gene MCPH1.

Microcephalin (MCPH1) is a key factor in our brain development and, in particular, eventual brain size. Mutations in the gene can lead to the developmental disorder microcephaly, which is characterized by a tiny brain.

Agree or Disagree?

According to two papers published in Cell on January 11, 2018, the making of memories and the processes of learning resemble, of all things, a viral infection. It works like this: The shells that transport information between neurons are assembled by a gene called Arc. Experiments conducted by two research teams revealed that the Arc protein that forms a shell, functions much like a Gag, a gene that transports a virus’s genetic material between cells during an infection. For example, the retrovirus HIV uses a Gag in exactly this manner.

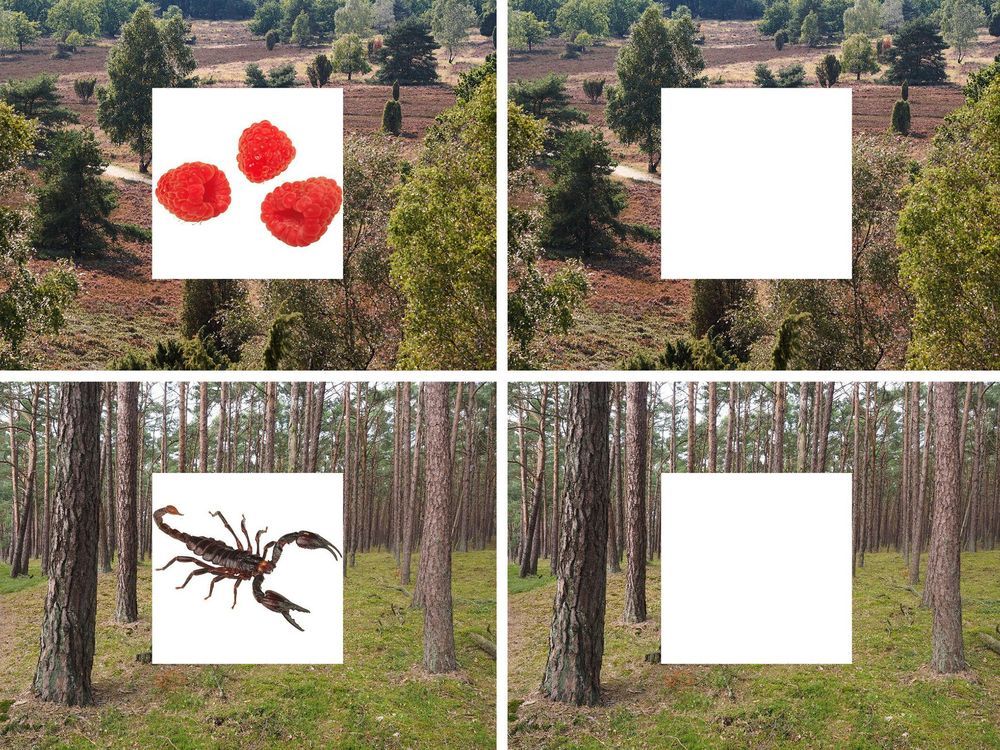

When looking at a picture of a sunny day at the beach, we can almost smell the scent of sun screen. Our brain often completes memories and automatically brings back to mind the different elements of the original experience. A new collaborative study between the Universities of Birmingham and Bonn now reveals the underlying mechanisms of this auto-complete function. It is now published in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers presented participants with a number of different scene images. Importantly, they paired each scene image with one of two different objects, such as a raspberry or a scorpion. Participants were given 3 seconds to memorise a given scene-object combination. After a short break they were presented with the scene images again, but now had to reconstruct the associated object image from memory.

“At the same time, we examined participants’ brain activation,” explains Prof. Florian Mormann, who heads the Cognitive and Clinical Neurophysiology group at the University of Bonn Medical Centre. “We focused on two brain regions – the hippocampus and the neighbouring entorhinal cortex.” The hippocampus is known to play a role in associative memory, but how exactly it does so has remained poorly understood.

Using genetic and survey data gathered from individuals via the UK Biobank, 23andMe, and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, they set out to see if any of the genes, or gene variants, were associated with depression either alone or when combined with an environmental factor like childhood trauma or socioeconomic diversity.

A new study assessing data from 620,000 individuals found that the 18 most highly-studied candidate genes for depression are no more associated with depression than randomly chosen genes.

Research out of the University of Colorado Boulder has dashed research into a potential link between certain genes and depression. The conclusion follows an analysis of both survey and genetic data from more than half a million people, which found that 18 candidate genes and random genes were equally associated with cases of depression.

The new study, which was recently published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, looked at 18 highly-studied ‘candidate genes,’ each of which had previously been studied in association with depression a minimum of 10 times. The results were called “a little bit stunning” by study senior author Matthew Keller.

According to the study, these 18 candidate genes weren’t associated with depression more than other randomly chosen genes. Past research into the genes that had indicated a link between the two were called false positives, though the researchers caution that this doesn’t mean depression isn’t heritable.

With its pudgy body, tired eyes and hair loss, the lower mouse could easily be the father of the sprightly and alert animal nestling alongside.

But they are actually the same age, the result of extraordinary trials of drugs which are slowing down or even reversing the ageing process.

Scientists now believe that ageing itself is responsible for many major conditions such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, arthritis, cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. And they think they have found a way to turn it off.