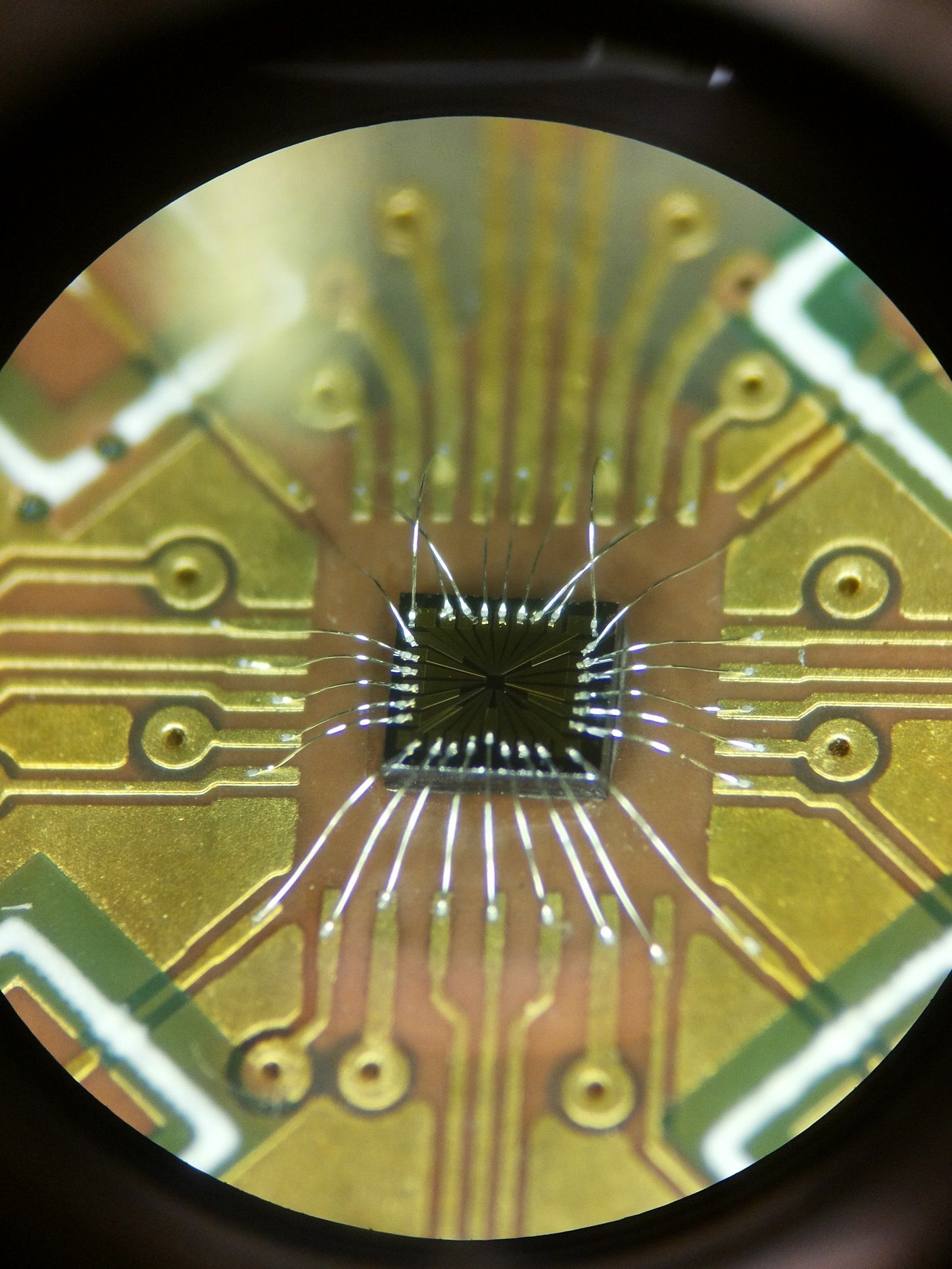

The unparalleled possibilities of quantum computers are currently still limited because information exchange between the bits in such computers is difficult, especially over larger distances. FOM workgroup leader Lieven Vandersypen and his colleagues within the QuTech research centre and the Kavli Institute for Nanosciences (Delft University of Technology) have succeeded for the first time in enabling two non-neighbouring quantum bits in the form of electron spins in semiconductors to communicate with each other. They publish their research on 10 October in Nature Nanotechnology.

Information exchange is something that we scarcely think about these days. People constantly communicate via e-mails, mobile messaging applications and phone calls. Technically, it is the bits in those various devices that talk to each other. “For a normal computer, this poses absolutely no problem,” says professor Lieven Vandersypen. “However, for the quantum computer – which is potentially much faster than the current computers – that information exchange between quantum bits is very complex, especially over long distances.”

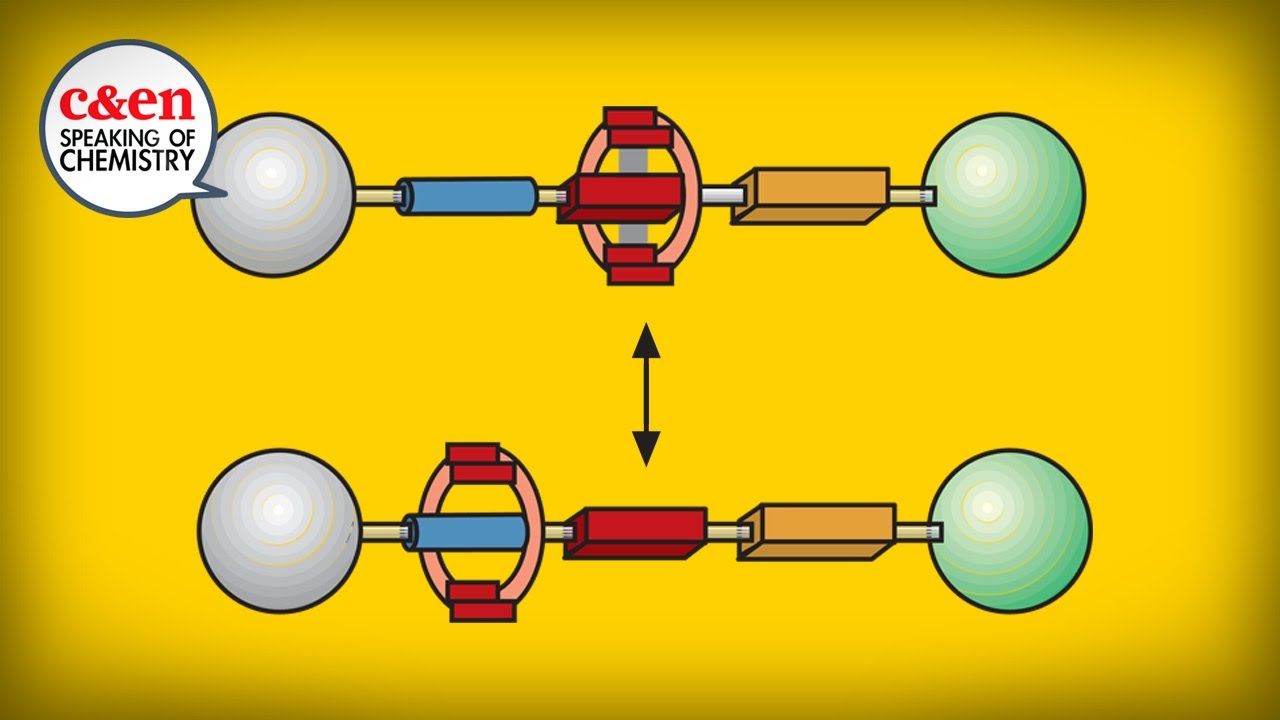

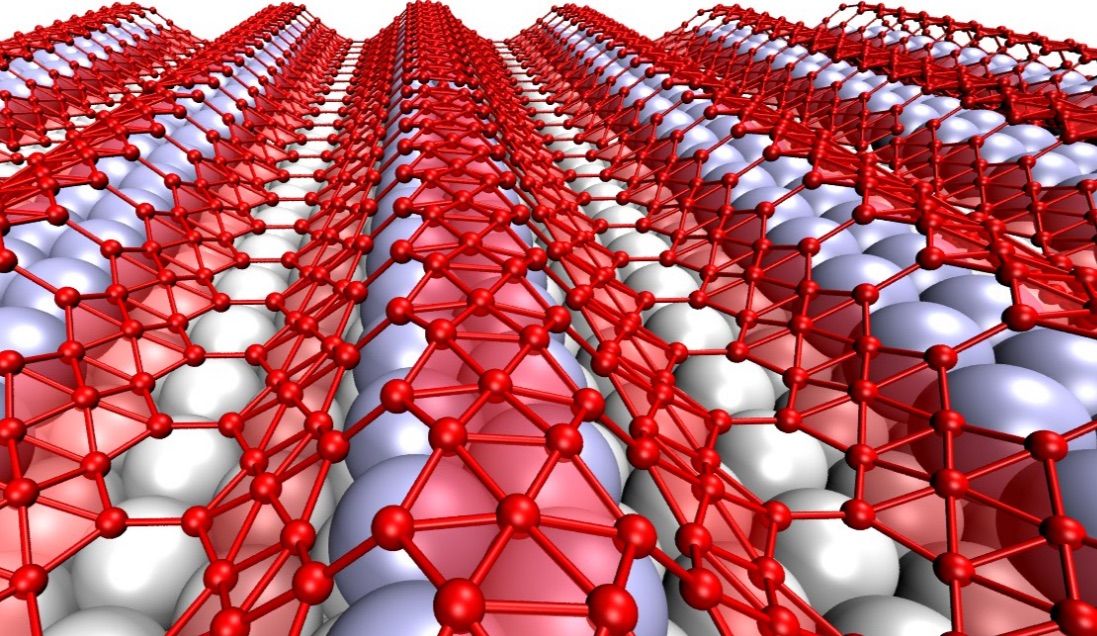

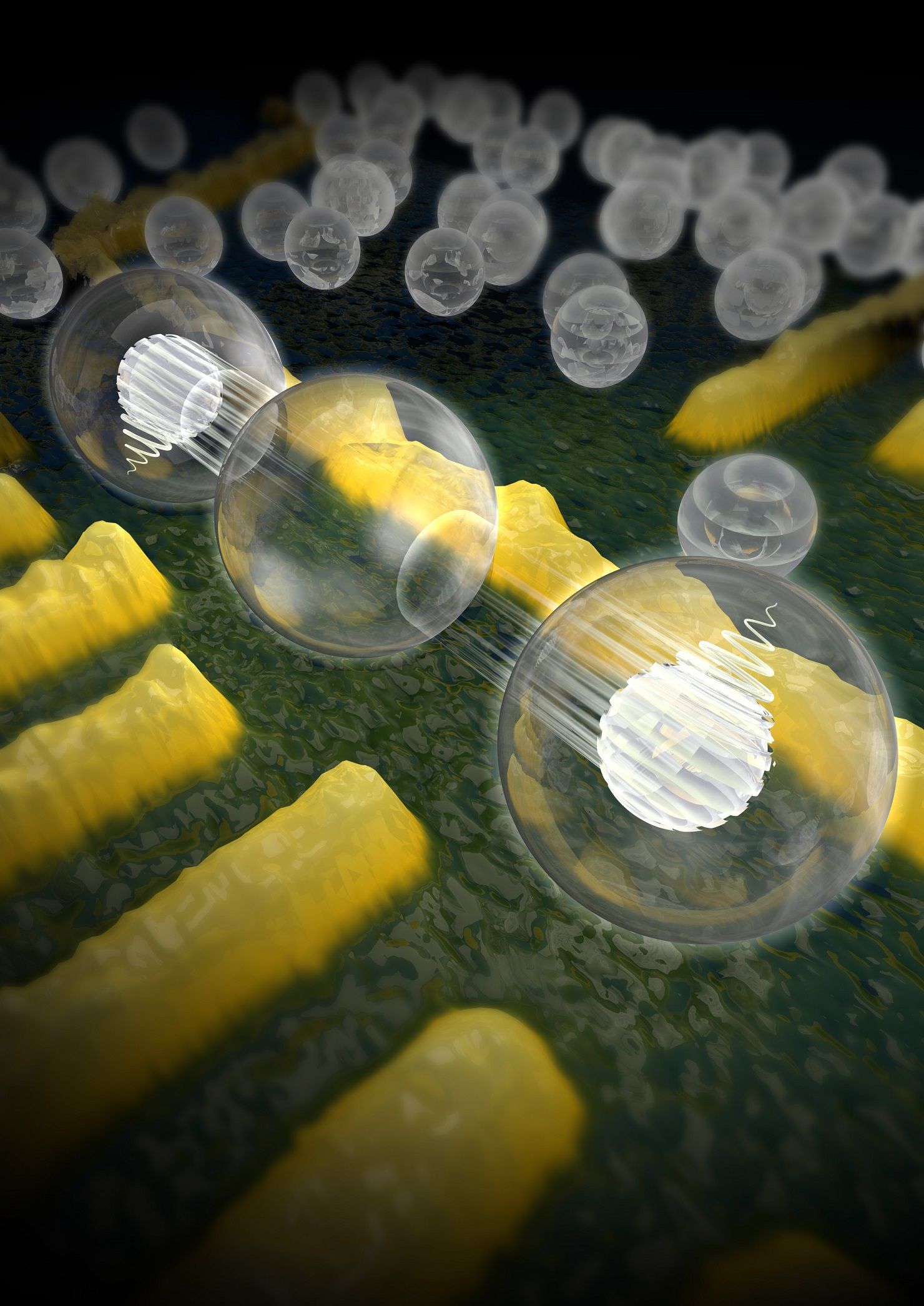

Mediating with quantum dots Artist impression of two electron spins that talk to each other via a ‘quantum mediator’. The two electrons are each trapped in a semiconductor nanostructure (quantum dot). The two spins interact, and this interaction is mediated by a third, empty quantum dot in the middle. In the future, coupling over larger distances can be achieved using other objects in between to mediate the interaction. This will allow researchers to create two-dimensional networks of coupled spins, that act as quantum bits in a future quantum computer. Copyright: Tremani/TU Delft.

Mediating with quantum dots Artist impression of two electron spins that talk to each other via a ‘quantum mediator’. The two electrons are each trapped in a semiconductor nanostructure (quantum dot). The two spins interact, and this interaction is mediated by a third, empty quantum dot in the middle. In the future, coupling over larger distances can be achieved using other objects in between to mediate the interaction. This will allow researchers to create two-dimensional networks of coupled spins, that act as quantum bits in a future quantum computer. Copyright: Tremani/TU Delft.