Mathematicians have confirmed that humanity’s collective attention span is getting shorter. And it’s not just social media that’s to blame.

Research reveals ‘social acceleration’ occurring across different domains. Samantha Page reports.

Most Hackaday readers are no doubt familiar with the Faraday cage, at least in name, and nearly everyone owns one: if you’ve ever stood watching a bag of popcorn slowly revolve inside of a microwave, you’be seen Michael Faraday’s 1836 invention in action. Yet despite being such a well known device, the average hacker still doesn’t have one in their arsenal. But why?

It could be that there’s a certain mystique about Faraday cages, an assumption that their construction requires techniques or materials outside the realm of the home hacker. While it’s true that building a perfect Faraday cage for a given frequency involves math and careful attention to detail, putting together a simple model for general purpose use and experimentation turns out to be quick and easy.

As an exercise in minimalist hacking I recently built a basic Faraday cage out of materials sourced from Home Depot, and thought it would be interesting to not only describe its construction but give some ideas as to how one can put it to practical use in the home lab. While it’s hardly a perfect specimen, it clearly works, and it didn’t take anything that can’t be sourced locally pretty much anywhere in the world.

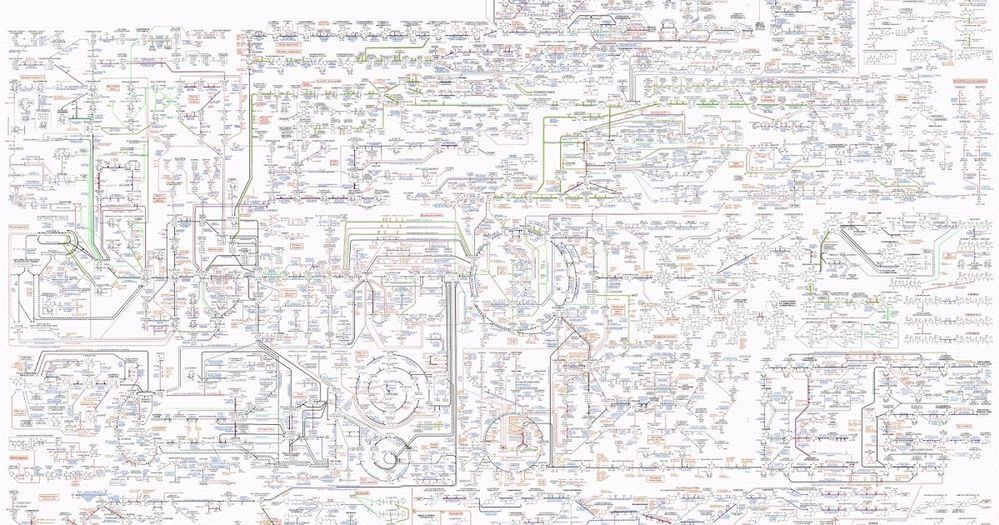

A team led by Lida Kanari now reports a new system for distinguishing cell types in the brain, an algorithmic classification method that the researchers say will benefit the entire field of neuroscience. Blue Brain founder Professor Henry Markram says, “For nearly 100 years, scientists have been trying to name cells. They have been describing them in the same way that Darwin described animals and trees. Now, the Blue Brain Project has developed a mathematical algorithm to objectively classify the shapes of the neurons in the brain. This will allow the development of a standardized taxonomy [classification of cells into distinct groups] of all cells in the brain, which will help researchers compare their data in a more reliable manner.”

The team developed an algorithm to distinguish the shapes of the most common type of neuron in the neocortex, the pyramidal cells. Pyramidal cells are distinctively tree-like cells that make up 80 percent of the neurons in the neocortex, and like antennas, collect information from other neurons in the brain. Basically, they are the redwoods of the brain forest. They are excitatory, sending waves of electrical activity through the network, as people perceive, act, and feel.

The father of modern neuroscience, Ramón y Cajal, first drew pyramidal cells over 100 years ago, observing them under a microscope. Yet up until now, scientists have not reached a consensus on the types of pyramidal neurons. Anatomists have been assigning names and debating the different types for the past century, while neuroscience has been unable to tell for sure which types of neurons are subjectively characterized. Even for visibly distinguishable neurons, there is no common ground to consistently define morphological types.

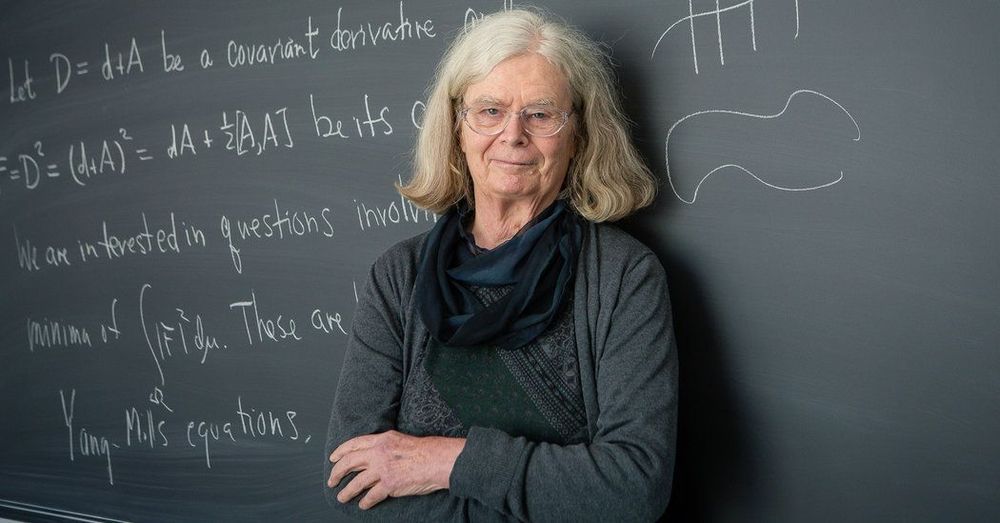

The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters today announced that Karen Uhlenbeck has won the 2019 Abel Prize, a Nobel-level honor in math. Uhlenbeck won for her foundational work in geometric analysis, which combines the technical power of analysis—a branch of math that extends and generalizes calculus—with the more conceptual areas of geometry and topology. She is the first woman to receive the prize since the award of 6 million Norwegian kroner (approximately $700,000) was first given in 2003.

Karen Uhlenbeck is first woman to receive the honor.

For the first time, one of the top prizes in mathematics has been given to a woman.

On Tuesday, the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters announced it has awarded this year’s Abel Prize — an award modeled on the Nobel Prizes — to Karen Uhlenbeck, an emeritus professor at the University of Texas at Austin. The award cites “the fundamental impact of her work on analysis, geometry and mathematical physics.”

One of Dr. Uhlenbeck’s advances in essence described the complex shapes of soap films not in a bubble bath but in abstract, high-dimensional curved spaces. In later work, she helped put a rigorous mathematical underpinning to techniques widely used by physicists in quantum field theory to describe fundamental interactions between particles and forces.