A mathematical equation has proven that controlling one of the two major changes in a cell—decay or cancerous growth—enhances the other, causing inevitable death.

A mathematical equation has proven that controlling one of the two major changes in a cell—decay or cancerous growth—enhances the other, causing inevitable death.

For decades, physicists, engineers and mathematicians have failed to explain a remarkable phenomenon in fluid mechanics: the natural tendency of turbulence in fluids to move from disordered chaos to perfectly parallel patterns of oblique turbulent bands. This transition from a state of chaotic turbulence to a highly structured pattern was observed by many scientists, but never understood.

At EPFL’s Emerging Complexity in Physical Systems Laboratory, Tobias Schneider and his team have identified the mechanism that explains this phenomenon. Their findings have been published in Nature Communications.

Frank Jennings Tipler is a mathematical physicist and cosmologist, holding a joint appointment in the Departments of Mathematics and Physics at Tulane University. He holds a BS in Physics from MIT and a PhD from the University of Maryland.

Watch his interview below on eternal life. To watch more interviews on this topic, click here: https://bit.ly/2wcTT1N

A growing body of research suggests that exposure to air pollution in the earliest stages of life is associated with negative effects on cognitive abilities. A new study led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a centre supported by “la Caixa”, has provided new data: exposure to particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 μm (PM2.5) during pregnancy and the first years of life is associated with a reduction in fundamental cognitive abilities, such as working memory and executive attention.

The study, carried out as part of the BREATHE project, has been published in Environmental Health Perspectives. The objective was to build on the knowledge generated by earlier studies carried out by the same team, which found lower levels of cognitive development in children attending schools with higher levels of traffic-related air pollution.

The study included 2,221 children between 7 and 10 years of age attending schools in the city of Barcelona. The children’s cognitive abilities were assessed using various computerized tests. Exposure to air pollution at home during pregnancy and throughout childhood was estimated with a mathematical model using real measurements.

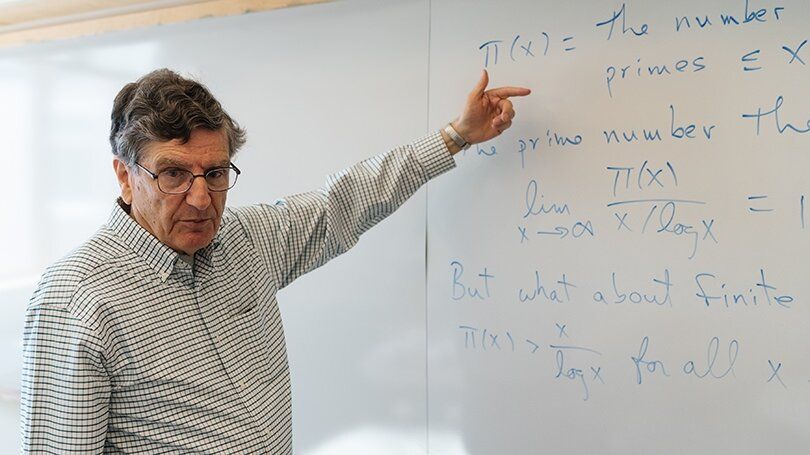

Many ways to approach the Riemann Hypothesis have been proposed during the past 150 years, but none of them have led to conquering the most famous open problem in mathematics. A new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) suggests that one of these old approaches is more practical than previously realized.

“In a surprisingly short proof, we’ve shown that an old, abandoned approach to the Riemann Hypothesis should not have been forgotten,” says Ken Ono, a number theorist at Emory University and co-author of the paper. “By simply formulating a proper framework for an old approach we’ve proven some new theorems, including a large chunk of a criterion which implies the Riemann Hypothesis. And our general framework also opens approaches to other basic unanswered questions.”

The paper builds on the work of Johan Jensen and George Pólya, two of the most important mathematicians of the 20th century. It reveals a method to calculate the Jensen-Pólya polynomials—a formulation of the Riemann Hypothesis—not one at a time, but all at once.

A mathematician from the University of Bristol has found a solution to part of a 64-year old mathematical problem – expressing the number 33 as the sum of three cubes.

Since the 1950s, mathematicians have wondered if all whole numbers could be expressed as the sum of three cubes; whether the equation k = x³+ y³+ z³ always has a solution.

The puzzle is a Diophantine equation in the field of number theory, and forms part of one of the most mysterious and wickedly hard problems in mathematics. We still don’t know the answer.

A prime number theory equation by mathematics professor emeritus Carl Pomerance turned up on The Big Bang Theory, where it was scrawled on a white board in the background of the hit sitcom about a group of friends and roommates who are scientists, many of them physicists at the California Institute of Technology.

In a recent paper, “Proof of the Sheldon Conjecture,” Pomerance, the John G. Kemeny Parents Professor of Mathematics Emeritus, does the math on a claim by fictional quantum physicist Sheldon Cooper that 73 is “the best number” because of several unique properties. Pomerance’s proof shows that 73 is indeed unique.

The Big Bang Theory is known for dressing the set with “Easter eggs” to delight the self-avowed science nerds in the audience. When UCLA physics professor David Saltzberg, technical consultant for The Big Bang Theory, heard about the Sheldon proof, he contacted Pomerance to ask if they could use it in the show, which was broadcast April 18.