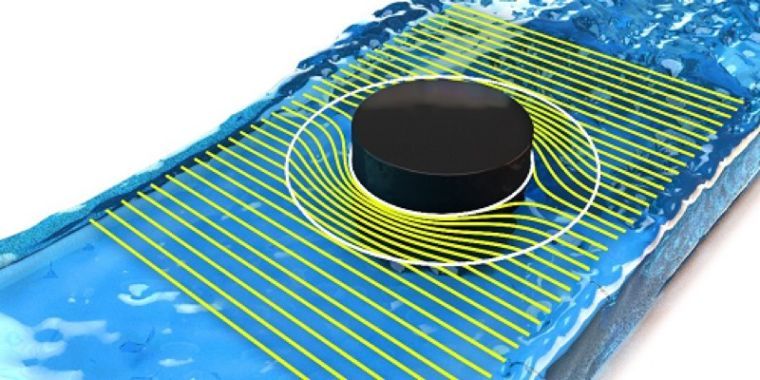

Supersolids, solid materials with superfluid properties (i.e., in which a substance can flow with zero viscosity), have recently become the focus of numerous physics studies. Supersolids are paradoxical phases of matter in which two distinct and somewhat antithetical orders coexist, resulting in a material being both crystal and superfluid.

First predicted at the end of the 1960s, supersolidity has gradually become the focus of a growing number of research studies, sparking debate across different scientific fields. Several years ago, for instance, a team of researchers published controversial results that identified this phase in solid helium, which were later disclaimed by the authors themselves.

A key issue with this study was that it did not account for the complexity of helium and the unreliable observations that it can sometimes produce. In addition, in atoms, interactions are typically very strong and steady, which makes it harder for this phase to occur.