A team of researchers from the University of Washington has found evidence that the Earth’s atmosphere approximately 2.7 billion years ago might have been up to 70 percent carbon dioxide. In their paper published in the journal Science Advances, the group describes their study of micrometeorites and what they learned from them.

As scientists continue to study Earth’s past, they look for evidence of what environmental conditions might have been like in hopes of understanding how life arose. One important piece of the puzzle is the atmosphere. Scientists suspect that its ingredients were far different billions of years ago, but they have little in the way of evidence to prove it. In this new endeavor, the researchers looked to micrometeorites as a possible source of clues. Their thinking was that any material from space that made its way to the surface of the planet had to travel first through the atmosphere—and any material that travels through the atmosphere is highly influenced by its materials, largely due to the high temperatures of atmospheric entry.

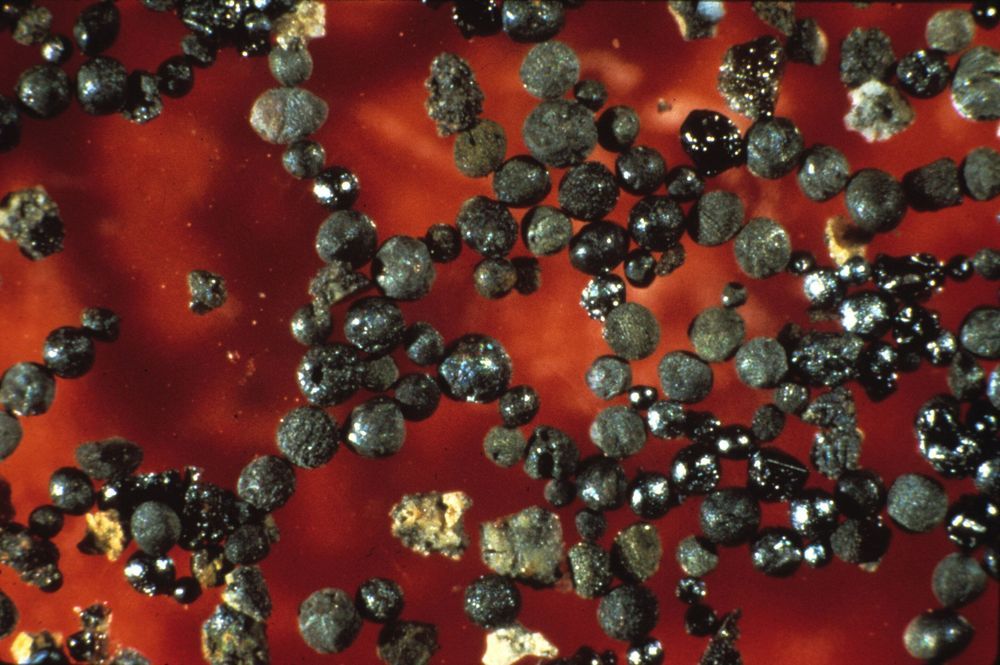

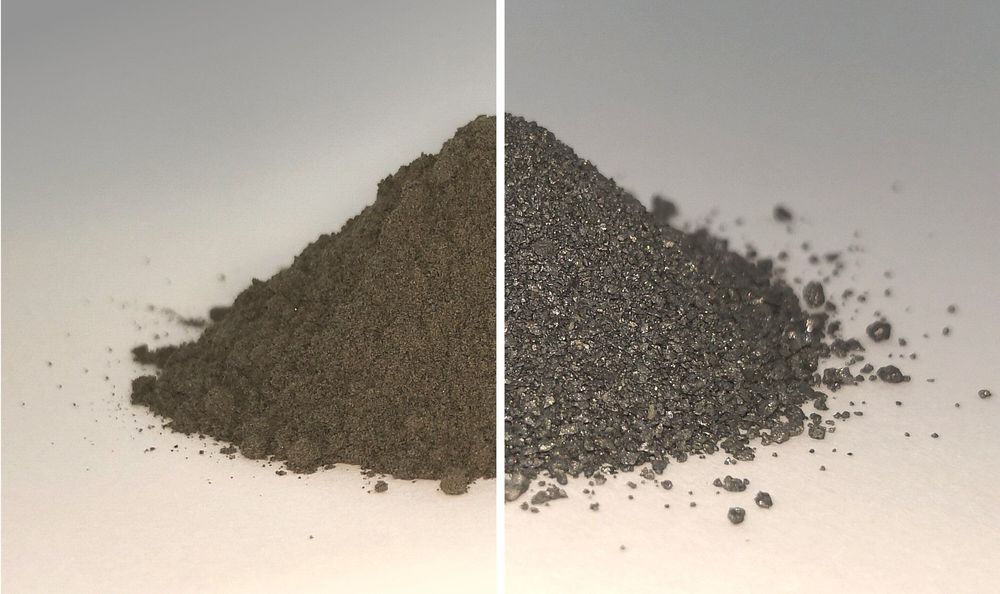

Several years ago, researchers found a host of micrometeorites that had landed on Earth approximately 2.7 billion years ago, putting them squarely in the Archean Eon—the time during which it is believed life first appeared on Earth. Study of the micrometeorites showed that they contained high levels of iron along with wüstite. Wüstite forms when iron is exposed to oxygen, but not on the Earth’s surface. It must have been created as the grain-sized meteorites burned and fell through the Earth’s atmosphere. Intrigued by the finding, the researchers created a computer model to simulate the conditions that would lead to the creation of materials such as wüstite on a rock falling through the atmosphere.