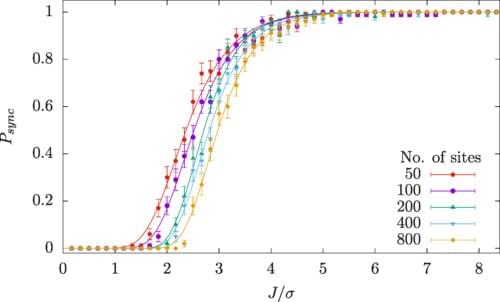

Physicists from Trinity have unlocked the secret that explains how large groups of individual “oscillators”—from flashing fireflies to cheering crowds, and from ticking clocks to clicking metronomes—tend to synchronize when in each other’s company.

Their work, just published in the journal Physical Review Research, provides a mathematical basis for a phenomenon that has perplexed millions—their newly developed equations help explain how individual randomness seen in the natural world and in electrical and computer systems can give rise to synchronization.

We have long known that when one clock runs slightly faster than another, physically connecting them can make them tick in time. But making a large assembly of clocks synchronize in this way was thought to be much more difficult—or even impossible, if there are too many of them.