Researchers found that the cephalopod is the only creature that can edit its RNA outside the nucleus. It’s a tool that may one day help genetic medicine.

A new genomics study of shark DNA, including from great white and great hammerhead sharks, reveals unique modifications in their immunity genes that may underlie the rapid wound healing and possibly higher resistance to cancers in these ocean predators. This research brings us a few steps closer to understanding, from a genetic sense, why sharks exhibit some characteristics that are highly desirable by humans.

Differences in the rate that genetic mutations accumulate in healthy young adults could help predict remaining lifespan in both sexes and the remaining years of fertility in women, according to University of Utah Health scientists. Their study, believed to be the first of its kind, found that young adults who acquired fewer mutations over time lived about five years longer than those who acquired them more rapidly.

The researchers say the discovery could eventually lead to the development of interventions to slow the aging process.

“If the results from this small study are validated by other independent research, it would have tremendous implications,” says Lynn B. Jorde, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Human Genetics at U of U Health and a co-author of the study. “It would mean that we could possibly find ways to fix ourselves and live longer and better lives.”

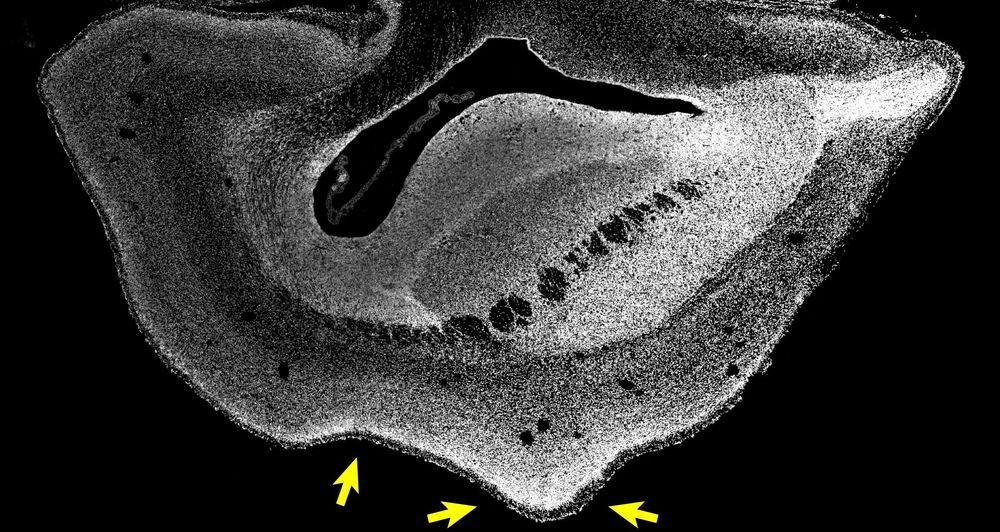

The expansion of the human brain during evolution, specifically of the neocortex, is linked to cognitive abilities such as reasoning and language. A certain gene called ARHGAP11B that is only found in humans triggers brain stem cells to form more stem cells, a prerequisite for a bigger brain. Past studies have shown that ARHGAP11B, when expressed in mice and ferrets to unphysiologically high levels, causes an expanded neocortex, but its relevance for primate evolution has been unclear.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, together with colleagues at the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (CIEA) in Kawasaki and the Keio University in Tokyo, both located in Japan, now show that this human-specific gene, when expressed to physiological levels, causes an enlarged neocortex in the common marmoset, a New World monkey. This suggests that the ARHGAP11B gene may have caused neocortex expansion during human evolution. The researchers published their findings in the journal Science.

The human neocortex, the evolutionarily youngest part of the cerebral cortex, is about three times bigger than that of the closest human relatives, chimpanzees, and its folding into wrinkles increased during evolution to fit inside the restricted space of the skull. A key question for scientists is how the human neocortex became so big. In a 2015 study, the research group of Wieland Huttner, a founding director of the MPI-CBG, found that under the influence of the human-specific gene ARHGAP11B, mouse embryos produced many more neural progenitor cells and could even undergo folding of their normally unfolded neocortex. The results suggested that the gene ARHGAP11B plays a key role in the evolutionary expansion of the human neocortex.

:oooooo.

The battle of the sexes is a never-ending war waged within ourselves as male and female elements of our own bodies continually fight each other for supremacy. This is the astonishing implication of a pioneering study showing that it is possible to flick a genetic switch that turns female ovary cells into male testicular tissue.

For decades, the battle of the sexes has been accepted by biologists as a real phenomenon with males and females competing against each other — when their interests do not coincide — for the continued survival of their genes in the next generation. Now scientists have been able to show that a gender war is constantly raging between the genes and cells of one individual.

One of the great dogmas of biology is that gender is fixed from birth, determined by the inheritance of certain genes on the X and Y sex chromosomes. But this simplistic idea has been exploded by the latest study, which demonstrated that fully-developed adult females can undergo a partial sex change following a genetic modification to a single gene.

:ooooooo.

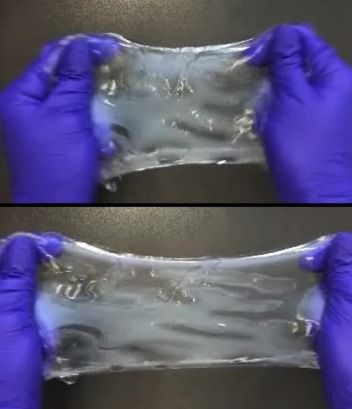

Superhero-like stretching capabilities aren’t just for Elastigirl. Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have come up with a new technology that can make any tissue sample exceptionally flexible.

ELAST technology (Entangled Link-Augmented Stretchable Tissue-hydrogel) is a chemical process that makes tissue samples very thin, very stretchy, compressible, and borderline indestructible. With it, lab technicians can more quickly and easily conduct fluorescent labeling in cells, proteins, or other genetic materials within organs like the brain or lungs. That, in turn, could enable faster research discoveries.

The MIT researchers published their work last month in the journal Nature Methods.

Human appetites have transformed the tomato — DNA and all. After centuries of breeding, what was once a South American berry roughly the size of a pea now takes all sorts of shapes and sizes, from cherry-like to hefty heirloom fruit.

Today, scientists are teasing out how these physical changes show up at the level of genes — work that could guide modern efforts to tweak the tomato, says Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator Zachary Lippman.

He and colleagues have now identified long-concealed hidden mutations within the genomes of 100 types of tomato, including an orange-berried wild plant from the Galapagos Islands and varieties typically processed into ketchup and sauce.

One of the biggest concerns that space agencies like NASA and SpaceX have when it comes to bringing humans to Planet Mars is survival.

Humans are poorly suited to life in space. The BBC reports:

We are products of 3.8 billion years of evolution in a comfy 1g oxygen-rich biosphere, protected by a magnetic bubble (the magnetosphere) from the harshness of the Universe. Away from the Earth, astronauts are bombarded by cosmic radiation and suffer nausea, muscle and bone loss, deteriorating eyesight and even weakened immune systems as a result of zero gravity.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have transformed the treatment of refractory blood cancers. These genetically engineered immune cells seek out and destroy cancer cells with precision. Now, scientists at Memorial Sloan Kettering are deploying them against other diseases, including those caused by senescence, a chronic “alarm state” in tissues. The scope of such ailments is vast and includes debilitating conditions, such as fibrotic liver disease, atherosclerosis, and diabetes.

Key to the success of CAR T cell therapy has been finding a good target. The first US Food and Drug Administration-approved CAR T cells target a molecule on the surface of blood cancers called CD19. It is present on cancer cells but few other normal cells, so side effects are limited.

Taking their cue from this prior work, a team of investigators including Scott Lowe, Chair of the Cancer Biology and Genetics Program in the Sloan Kettering Institute, and Michel Sadelain, Director of the Center for Cell Engineering at MSK, along with their trainees Corina Amor, Judith Feucht, and Josef Leibold, sought to identify a target on senescent cells. These cells no longer divide, but they actively send “help me” signals to the immune system.

A human embryo editing experiment gone wrong has scientists warning against treading into the field altogether.

To understand the role of a single gene in early human development, a team of scientists at the London-based Francis Crick Institute removed it from a set of 18 donated embryos. Even though the embryos were destroyed after just 14 days, that was enough time for the single edit to transform into “major unintended edits,” OneZero reports.

Human gene editing is a taboo topic — the birth of two genetically modified babies in 2018 proved incredibly controversial, and editing embryos beyond experimentation is not allowed in the U.S. The scientists in London conducted short-term research on a set of 25 donated embryos, using the CRISPR technique to remove a gene from 18 of them. An analysis later revealed 10 of those edited embryos looked normal, but that the other eight revealed “abnormalities across a particular chromosome,” OneZero writes. Of them, “four contained inadvertent deletions or additions of DNA directly adjacent to the edited gene,” OneZero continues.