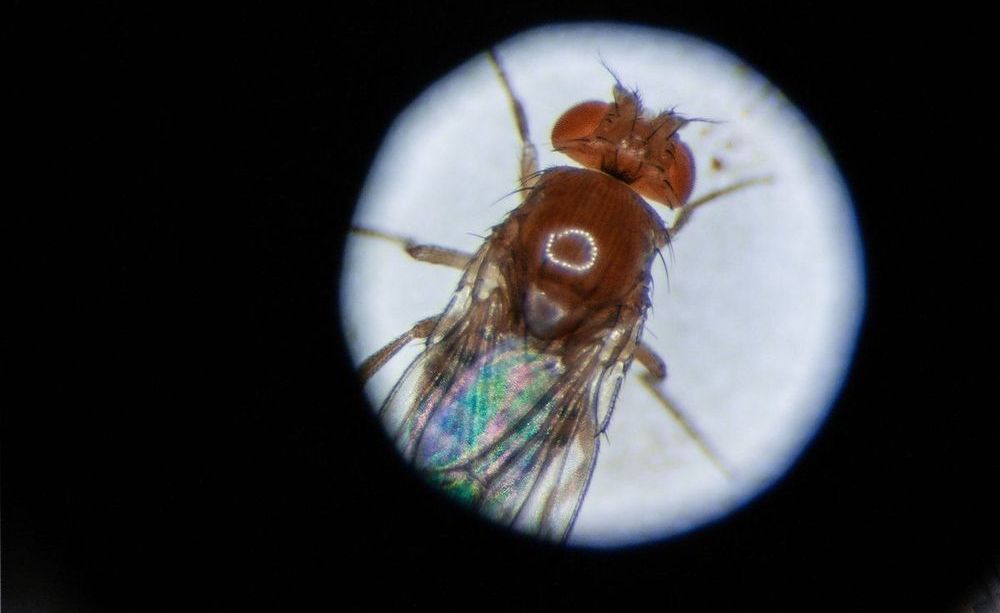

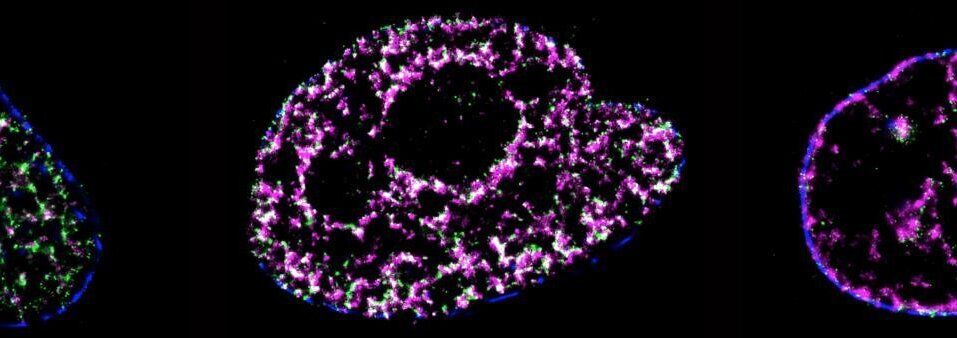

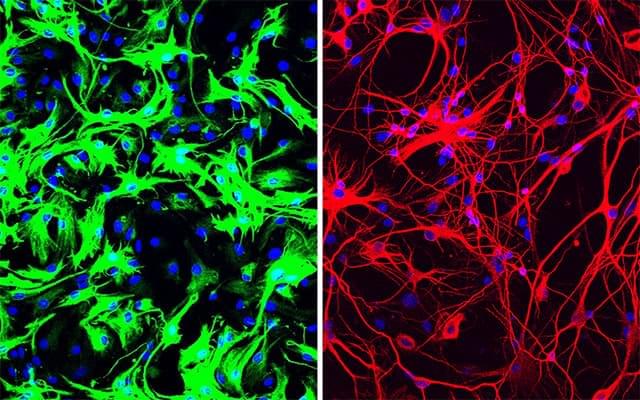

Ribonucleic acid, or RNA, is part of our genetic code and present in every cell of our body. The best known form of RNA is a single linear strand, of which the function is well known and characterized. But there is also another type of RNA, so-called “circular RNA,” or circRNA, which forms a continuous loop that makes it more stable and less vulnerable to degradation. CircRNAs accumulate in the brain with age. Still, the biological functions of most circRNAs are not known and are a riddle for the scientific community. Now scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Aging have come one step closer to answer the question what these mysterious circRNAs do: one of them contributes to the aging process in fruit flies.

Carina Weigelt and other researchers in the group led by Linda Partridge, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Aging, used fruit flies to investigate the role of the circRNAs in the aging process. “This is unique, because it is not very well understood what circRNAs do, especially not in an aging perspective. Nobody has looked at circRNAs in a longevity context before,” says Carina Weigelt who conducted the main part of the study. She continues: “Now we have identified a circRNA that can extend lifespan of fruit flies when we increase it, and it is regulated by insulin signaling.”