Humans have long recognized the song of trees.

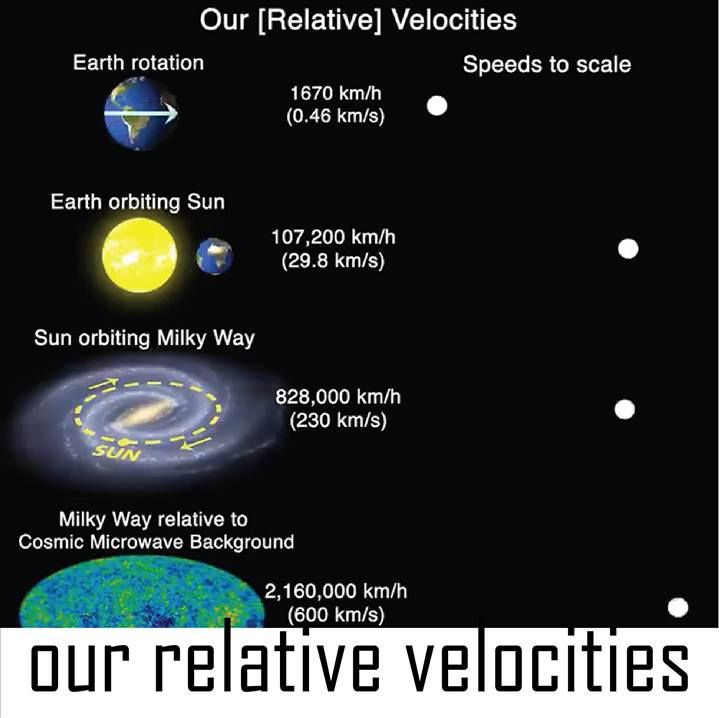

Everything is moving. Our relative velocities.

Israel recently offered a first taste of its planned pavilion at the Expo 2020 in Dubai, under the headline “Towards tomorrow,” that hopes to showcase Israeli innovation to the Arab World and beyond.

A short clip posted on several of the Foreign Ministry’s social media accounts shows a simulation of the pavilion, which is described as an “icon, hope and aspiration” and appears to focus on Israeli innovation and technology.

The pavilion has “no walls and no borders,” according to the narrator of the short clip. “An open invitation to join hands on the amazing journey forward and to shape our future together.”

What might the end of work mean for the future of buildings? Firstly, a significant proportion of the built environment that has up to now been designed for people-centred economic activities —offices, shopping centers, banks, factories and schools—may over the next 10–20 years house 50% or less of the number of workers with far fewer physical customers. Furthermore, with the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), some organizations might run on algorithm alone with literally no human staff.

The future of jobs is not just about employment, but about larger societal shifts with dramatic impact on the use of space and resources. Indeed, AI is increasingly likely to provide a meta-level management layer — collating data from a variety from a range of sources to monitor and control every aspect of the built environment and the use of resources within it.

Today, at the dawn of the AI revolution, some of the latest technology coming at us involves mixed reality; advances in virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are buzzing with new uses in places of work, education and various commercial settings. Teaching and training are exemplary uses — enabling dangerous, rare or just everyday situations to be simulated for trainees. Such simulations also provide the nexus point for humans to work alongside AI. For example, robot surgeons might do the cutting, while a human surgeon looks on remotely via video or a VR/AR interface. How might places be redesigned to accommodate this human-AI hybrid job future? The outcome could be spaces that embrace the blurring of physical and digital worlds, possibly with multi-sensory connection points between the two.

The coming wave of AI in business and society could impact the future design, use and management of buildings in dramatic ways. Key design features, including construction, security, monitoring and maintenance, could become coordinated by highly automated AI neural networks. For example, future office buildings might make intelligent responses to their inhabitants’ moods or feelings in order to increase productivity of humans in the organization—varying lighting, temperature, background music, ambient smells, and digital wallpaper displays according to the motivational needs of each worker.

In the post-work, shared infrastructure economy architects could also factor in ‘multi-purposing’ in the design of new buildings and the remodelling of existing ones. For example, why couldn’t schools double as courtrooms, doctor’s, surgeries, social centres, libraries, etc. in the evenings and during holidays?

Empty space could become more and more of a liability to towns and cities as retail and education move online. In the USA up to 1,000 retail outlets a week are currently being closed. A Texas firm has suggested a design for old shopping malls and retail outlets as drone ports, for example. Other options might include repurposing them as maker spaces, community centres, pop-up cafes, and adult learning outlets. The pace of automation of retail and commerce is likely to be exponential: imagine a chatbot that could coordinate drone deliveries of the groceries ordered by web-connected smart refrigerators that run on IBMs Watson AI platform. Intuitive and predictive AI seems set to revolutionize the home and business.

As advances in the cognitive sciences accelerate, there is growing fascination with the idea of neuro-architecture as control mechanism in a post-work society: will mass automation and efficiency expectations justify the construction of buildings that are responsive to people’s needs, read moods, use biometrics, and conduct behavior-conditioning of employees? There are a number of reasons to think these strategies could become accepted practice. Many AI analysts argue that, rather than compete with robots, humans will do more meaningful and important work than ever. Hence, the use of building design to evoke certain feelings, enhance moods and creativity, and the use of behavioural insights to motivate the workforce could provide an important advantage in the new ‘cobot’ normal of humans working alongside intelligent robots.

As work becomes automated it also becomes more cloud-based and fewer offices need the amount of space they once did or for the purposes space once served. New uses of space to accommodate virtual AI workers and to provide a comfortable environment for human employees will be in demand. Furthermore, replacing actual workers with code means the layout, design and supplies necessary for the typical office would completely change. The role of AI in reducing the amount of people and ‘stuff’ places must accommodate should open up considerable opportunities for building redesign.

Designing to a post-job future doesn’t necessarily mean that high-tech has the advantage. There will be valuable opportunities to inject a touch of humanity to key settings where people will interact with AI —work, home and public spaces. The rise of AI means we must consider different visions of the future where 50% or more of the workforce is automated out of a job and the new sectors haven’t taken up all the displaced individuals. With the right perspective, positive design adjustments can help make the post-work future meaningful and more human. However, the transition will be challenging for all concerned.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

The authors are from Fast Future which publishes books from future thinkers around the world exploring how developments such as AI, robotics and disruptive thinking could impact individuals, society and business and create new trillion-dollar sectors. Fast Future has a particular focus on ensuring these advances are harnessed to unleash individual potential and enable a very human future. See: www.fastfuture.com

Rohit Talwar is a global futurist, keynote speaker, author, and CEO of Fast Future where he helps clients develop and deliver transformative visions of the future. He is the editor and contributing author for The Future of Business, editor of Technology vs. Humanity and co-editor of a forthcoming book on The Future of AI in Business.

Alexandra Whittington is a futurist, writer, faculty member on the Futures programme at the University of Houston and foresight director at Fast Future. She is a contributor to The Future of Business and a co-editor for forthcoming books on Unleashing Human Potential — The Future of AI in Business and 50:50 — Scenarios for the Next 50 Years.

Twitter http://twitter.com/fastfuture

Bloghttp://blog.fastfuturepublishing.com/

LinkedIn http://www.linkedin.com/in/talwar

With pollution a major issue for Paris and the city’s public transport bursting at the seams, one start-up has a solution involving the River Seine.

The Bubble, a “flying taxi”, is powered by electricity and lifts out of the water on “wings” – and boasts green credentials such as being noise and pollution-free. It costs around €200,000 to build and can reach speeds of up to 18 knots (20.7mph). Test voyages in Paris are limited to a maximum speed of 18.6mph.

The service could launch as early as spring next year, according to a press release from the Paris mayor’s office. The Seabubbles start-up launched a four-day test run on the Seine on Monday.

The disappearance of 40-year-old mortgage broker William Earl Moldt remained a mystery for 22 years because the technology used to find him hadn’t been developed yet.

Moldt was reported missing on November 8, 1997. He had left a nightclub around 11 p.m. where he had been drinking. He wasn’t known as a heavy drinker and witnesses at the bar said he didn’t seem intoxicated when he left.

The threats of cyberattack and hypersonic missiles are two examples of easily foreseeable challenges to our national security posed by rapidly developing technology. It is by no means certain that we will be able to cope with those two threats, let alone the even more complicated and unknown challenges presented by the general onrush of technology — the digital revolution or so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution — that will be our future for the next few decades.

Technology is about to upend our entire national security infrastructure.