The metazoan mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) is an ideal model system for comparative and evolutionary genomic research. The typical mitogenome of metazoans encodes a conserved set of 37 genes for 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), two ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes1, with genome-level characters, such as genome size, gene content, and gene order, display high diversity in some lineages2,3. Gene rearrangements are observed frequently in some groups, while gene duplication and loss are distributed sporadically in limited lineages such as Bivalvia, Cephalopod, and Afrobatrachia4,5,6. These remaining duplicate genes and pseudogenes represent important data for exploring the evolutionary history and mechanisms of gene rearrangement and recruitment. For the arrangement of mitochondrial genes, the variation in relative positions of PCGs and rRNA genes are more limited compared with that of tRNA genes across organisms within a phylum7. The tRNA genes with characteristics of diverse changes in relative position, gene content, and secondary structure, are considered as an important tool in studying the evolution of mitogenome, in particular to the rearrangement mechanism8,9,10. Additionally, its variation is usually linked to evolutionary relationships in a wide range of lineages at different taxonomic levels suggesting these features of tRNA could be utilized as useful phylogenetic markers11.

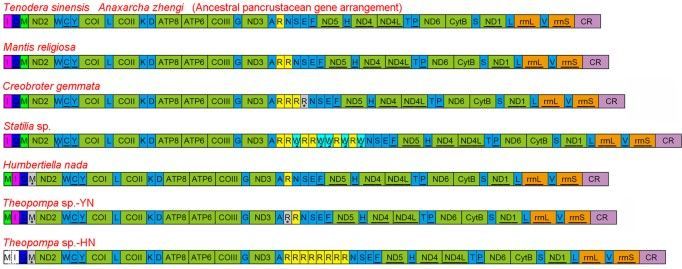

The extensive gene rearrangements (including PCGs and RNA) of insect mitogenomes have been detected in several lineages within the Diptera (Trichoceridae, Cecidomyiidae), Hemiptera (Enicocephalidae), Hymenoptera, Thysanoptera, Psocoptera and Phthiraptera12,13,14,15,16,17,18, while most of investigated mitogenomes share the same gene order with the hypothesized ancestral pancrustacean mitogenome arrangement19 or possess rare tRNA rearrangement. Previously reported dictyopteran mitogenomes consistently display the typical ancestral gene order and content, however only two species are praying mantises and the rest are cockroaches and termites. Members of the Mantodea, a separate lineage within the Dictyoptera, have evolved many unique morphological and behavioural features as the ambush and pursuit predators20,21,22. A better understanding of the diversity of mitogenome evolution in this enigmatic order underlines the need for exploring more taxa with the diverse praying mantis.

Herein, we report eight new mitogenomes from Mantodea and describe their general characteristics. Two new gene rearrangements and reassignment of tRNA genes are described, and evolutionary mechanisms for the gene rearrangements and duplication are discussed. Further, we examine the relationship between tRNA gene duplication and codon usage, and investigate whether these tRNA features vary with phylogeny.