“Using survey data from a sample of senior investment professionals from mainstream (i.e. not SRI funds) investment organizations we provide insights into why and how investors use reported environmental, social and governance (ESG) information.”

“Using survey data from a sample of senior investment professionals from mainstream (i.e. not SRI funds) investment organizations we provide insights into why and how investors use reported environmental, social and governance (ESG) information.”

A new well written but not very favorable write-up on #transhumanism. Despite this, more and more publications are tackling describing the movement and its science. My work is featured a bit.

On the eve of the 20th century, an obscure Russian man who had refused to publish any of his works began to finalize his ideas about resurrecting the dead and living forever. A friend of Leo Tolstoy’s, this enigmatic Russian, whose name was Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov, had grand ideas about not only how to reanimate the dead but about the ethics of doing so, as well as about the moral and religious consequences of living outside of Death’s shadow. He was animated by a utopian desire: to unite all of humanity and to create a biblical paradise on Earth, where we would live on, spurred on by love. He was an immortalist: one who desired to conquer death through scientific means.

Despite the religious zeal of his notions—which a number of later Christian philosophers unsurprisingly deemed blasphemy—Fyodorov’s ideas were underpinned by a faith in something material: the ability of humans to redevelop and redefine themselves through science, eventually becoming so powerfully modified that they would defeat death itself. Unfortunately for him, Fyodorov—who had worked as a librarian, then later in the archives of Ministry of Foreign Affairs—did not live to see his project enacted, as he died in 1903.

Fyodorov may be classified as an early transhumanist. Transhumanism is, broadly, a set of ideas about how to technologically refine and redesign humans, such that we will eventually be able to escape death itself. This desire to live forever is strongly tied to human history and art; indeed, what may be the earliest of all epics, the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, portrays a character who seeks a sacred plant in the black depths of the sea that will grant him immortality. Today, however, immortality is the stuff of religions and transhumanism, and how these two are different is not always clear to outsiders.

Contemporary schemes to beat death usually entail being able to “upload” our minds into computers, then downloading our minds into new, better bodies, cyborg or robot bodies immune to the weaknesses that so often define us in our current prisons of mere flesh and blood. The transhumanist movement—which is many movements under one umbrella—is understandably controversial; in 2004 in a special issue of Foreign Policy devoted to deadly ideas, Francis Fukuyama famously dubbed transhumanism one of the most dangerous ideas in human history. And many, myself included, have a natural tendency to feel a kind of alienation from, if not repulsion towards, the idea of having our bodies—after our hearts stop—flushed free of blood and filled with cryonic nitrogen, suspending us, supposedly, until our minds can be uploaded into a new, likely robotic, body—one harder, better, and faster, as Daft Punk might have put it.

Super-smart robots with artificial intelligence is pretty much a foregone conclusion: technology is moving in that direction with lightning speed. But what if those robots gain consciousness? Will they deserve the same rights as humans? The ethics of this are tricky. Explore them in the video below.

“As academics we can sign petitions, but it is not enough.”

As academics we can sign petitions, but it is not enough. Scott Aaronson wrote very eloquently about this issue after the initial ban was announced (see also Terry Tao). My department has seen a dramatic decrease in the number of applicants in general and not just from Iran. We were just informed that we can no longer make Teaching Assistant offers for students who are unlikely to get a visa to come here.

The Department of Homeland Security has demonstrated its blatant disregard for moral norms. Why should we trust its scientific norms? What confidence do we have that funding will not be used in some coercive way? What does it say to our students when we ask them to work for DHS? Yes, the government is big, but at some point the argument that it’s mostly the guy at the top who is bad but the rest of the agency is still committed to good science becomes just too hard to swallow. I decided that I can’t square that circle. Each one of us should think hard about whether we want to.

Here’s my take on why the overpopulation objection to rejuvenation is morally unacceptable.

In this article, I’ll try to show that the overpopulation objection against rejuvenation is morally deplorable. For this purpose, whether or not the world is overpopulated or might be such in the future doesn’t matter. I’ll deal with facts and data in the two other articles dedicated to this objection; for now, all I want is getting to the conclusion that not developing rejuvenation for the sake of avoiding overpopulation is morally unacceptable (especially when considering the obvious and ethically more sound alternative), and thus overpopulation doesn’t constitute a valid objection to rejuvenation.

I’ll start with an example. Imagine there’s a family of two parents and three children. They’re not doing too well financially, and they live packed in a tiny apartment with no chances of moving somewhere larger. Clearly they cannot afford having more children, but they would really like having more anyway. What should they do?

The only reasonable answer is that they should not have any more children until they can afford having them. Throwing away the old ones for the sake of some other child to be even conceived yet would be nothing short of sheer madness.

Posthumanists and perhaps especially transhumanists tend to downplay the value conflicts that are likely to emerge in the wake of a rapidly changing technoscientific landscape. What follows are six questions and scenarios that are designed to focus thinking by drawing together several tendencies that are not normally related to each other but which nevertheless provide the basis for future value conflicts.

Growing organs in the lab is an enduring sci-fi trope, but as stem cell technology brings it ever closer to reality, scientists are beginning to contemplate the ethics governing disembodied human tissue.

So-called organoids have now been created from gut, kidney, pancreas, liver and even brain tissue. Growing these mini-organs has been made possible by advances in stem cell technology and the development of 3D support matrices that allow cells to develop just like they would in vivo.

Unlike simple tissue cultures, they exhibit important structural and functional properties of organs, and many believe they could dramatically accelerate research into human development and disease.

That’s a relief.

Of all the potentially apocalyptic technologies scientists have come up with in recent years, the gene drive is easily one of the most terrifying. A gene drive is a tool that allows scientists to use genetic engineering to override natural selection during reproduction. In theory, scientists could use it to alter the genetic makeup of an entire species—or even wipe that species out. It’s not hard to imagine how a slip-up in the lab could lead to things going very, very wrong.

But like most great risks, the gene drive also offers incredible reward. Scientists are, for example, exploring how gene drive might be used to wipe out malaria and kill off Hawaii’s invasive species to save endangered native birds. Its perils may be horrifying, but its promise is limitless. And environmental groups have been campaigning hard to prevent that promise from ever being realized.

This week at the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity in Mexico, world governments rejected calls for a global moratorium on gene drives. Groups such Friends of the Earth and the Council for Responsible Genetics have called gene drive “gene extinction technology,” arguing that scientists “propose to use extinction as a deliberate tool, in direct contradiction to the moral purpose of conservation organizations, which is to protect life on earth.”

Yikes!

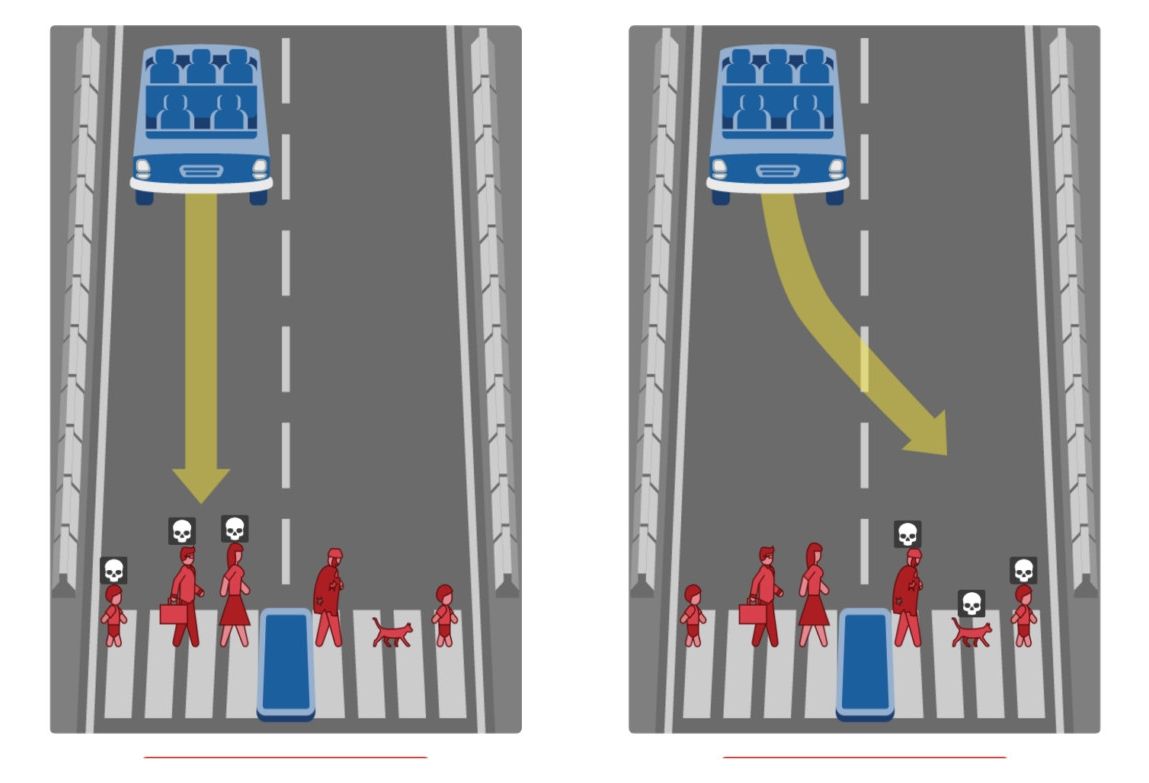

If there’s an unavoidable accident in a self-driving car, who dies? This is the question researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) want you to answer in ‘Moral Machine.’

The simplistic website is sort of like the famed ‘Trolley Problem’ on steroids. If you’re unfamiliar, according to Wikipedia, the Trolley Problem is as follows:

There is a runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track. You have two options: