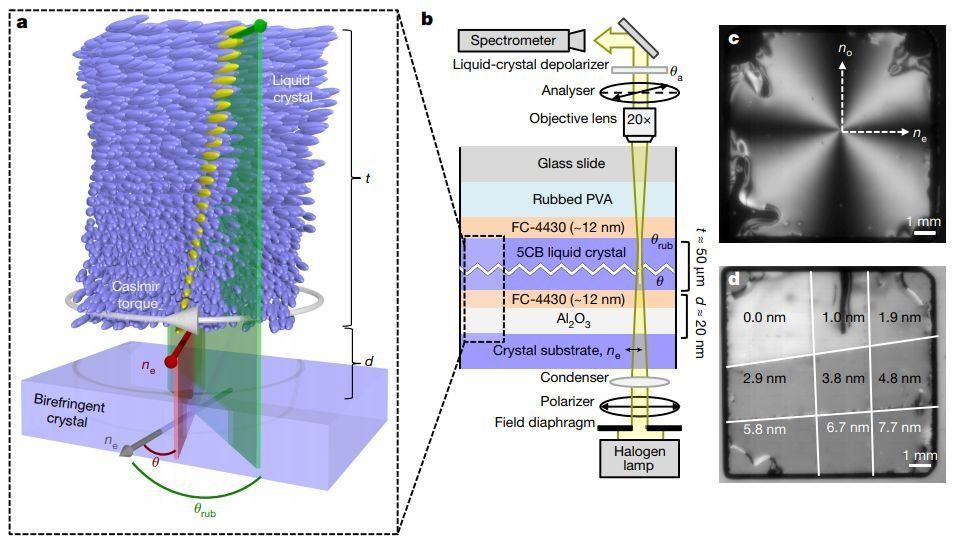

Researchers from the University of Maryland have for the first time measured an effect that was predicted more than 40 years ago, called the Casimir torque.

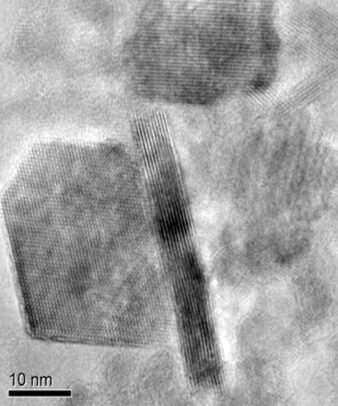

When placed together in a vacuum less than the diameter of a bacterium (one micron) apart, two pieces of metal attract each other. This is called the Casimir effect. The Casimir torque—a related phenomenon that is caused by the same quantum electromagnetic effects that attract the materials—pushes the materials into a spin. Because it is such a tiny effect, the Casimir torque has been difficult to study. The research team, which includes members from UMD’s departments of electrical and computer engineering and physics and Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics, has built an apparatus to measure the decades-old prediction of this phenomenon and published their results in the December 20th issue of the journal Nature.

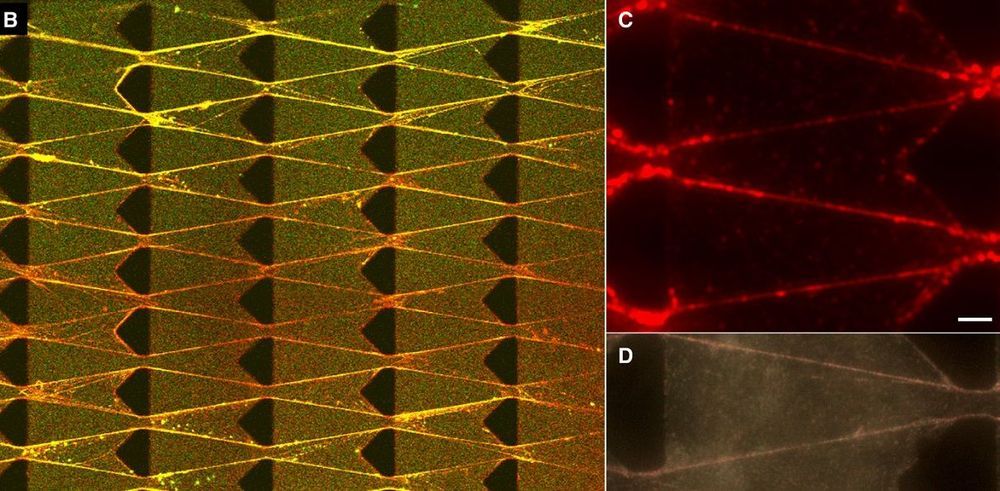

“This is an interesting situation where industry is using something because it works, but the mechanism is not well-understood,” said Jeremy Munday, the leader of the research. “For LCD displays, for example, we know how to create twisted liquid crystals, but we don’t really know why they twist. Our study proves that the Casimir torque is a crucial component of liquid crystal alignment. It is the first to quantify the contribution of the Casimir effect, but is not the first to prove that it contributes.”