[*This article was first published in the September 2017 issue of Paradigm Explorer: The Journal of the Scientific and Medical Network (Established 1973). The article was drawn from the author’s original work in her book: The Future: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2017), especially from Chapters 4 & 5.]

We are at a critical point today in research into human futures. Two divergent streams show up in the human futures conversations. Which direction we choose will also decide the fate of earth futures in the sense of Earth’s dual role as home for humans, and habitat for life. I choose to deliberately oversimplify here to make a vital point.

The two approaches I discuss here are informed by Oliver Markley and Willis Harman’s two contrasting future images of human development: ‘evolutionary transformational’ and ‘technological extrapolationist’ in Changing Images of Man (Markley & Harman, 1982). This has historical precedents in two types of utopian human futures distinguished by Fred Polak in The Image of the Future (Polak, 1973) and C. P. Snow’s ‘Two Cultures’ (the humanities and the sciences) (Snow, 1959).

What I call ‘human-centred futures’ is humanitarian, philosophical, and ecological. It is based on a view of humans as kind, fair, consciously evolving, peaceful agents of change with a responsibility to maintain the ecological balance between humans, Earth, and cosmos. This is an active path of conscious evolution involving ongoing psychological, socio-cultural, aesthetic, and spiritual development, and a commitment to the betterment of earthly conditions for all humanity through education, cultural diversity, greater economic and resource parity, and respect for future generations.

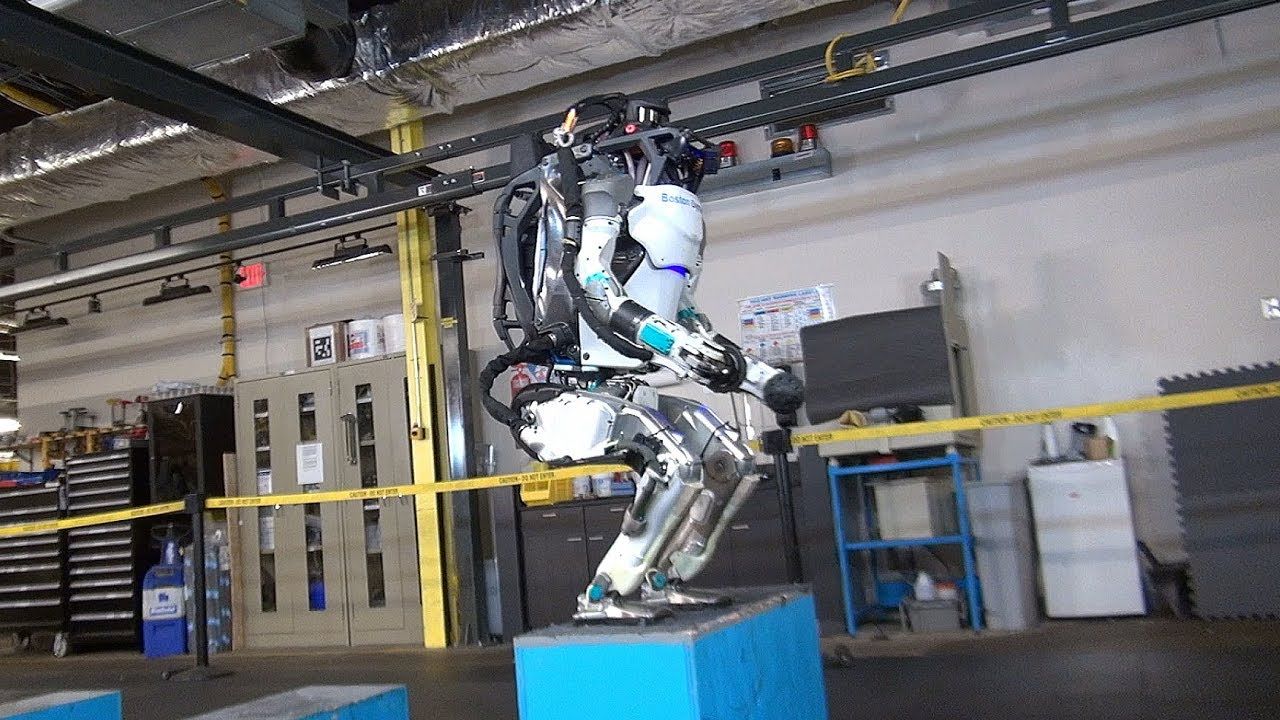

By contrast, what I call ‘technotopian futures’ is dehumanising, scientistic, and atomistic. It is based on a mechanistic, behaviourist model of the human being, with a thin cybernetic view of intelligence. The transhumanist ambition to create future techno-humans is anti-human and anti-evolutionary. It involves technological, biological, and genetic enhancement of humans and artificial machine ‘intelligence’. Some technotopians have transcendental dreams of abandoning Earth to build a fantasised techno-heaven on Mars or in satellite cities in outer space.

Interestingly, this contest for the control of human futures has been waged intermittently since at least the European Enlightenment. Over a fifty-year time span in the second half of the 18th century, a power struggle for human futures emerged, between human-centred values and the dehumanisation of the Industrial Revolution.

The German philosophical stream included the idealists and romantics, such as Herder, Novalis, Goethe, Hegel, and Schelling. They took their lineage from Leibniz and his 17th-century integral, spiritually-based evolutionary work. These German philosophers, along with romantic poets such as Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge (who helped introduce German idealism to Britain) seeded a spiritual-evolutionary humanism that underpins the human-centred futures approach (Gidley, 2007).

The French philosophical influence included La Mettrie’s mechanistic man and René Descartes’s early 17th-century split between mind and body, forming the basis of French (or Cartesian) Rationalism. These French philosophers, La Mettrie and Descartes, along with the theorists of progress such as Turgot and de Condorcet, were secular humanists. Secular humanism is one lineage of technotopian futures. Scientific positivism is another (Gidley, 2017).

Transhumanism, Posthumanism and the Superman Trope

Transhumanism in the popular sense today is inextricably linked with technological enhancement or extensions of human capacities through technology. This is a technological appropriation of the original idea of transhumanism, which began as a philosophical concept grounded in the evolutionary humanism of Teilhard de Chardin, Julian Huxley, and others in the mid-20th century, as we shall see below.

In 2005, the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford founded The Future of Humanity Institute and appointed Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom as its Chair. Bostrom makes a further distinction between secular humanism, concerned with human progress and improvement through education and cultural refinement, and transhumanism, involving ‘direct application of medicine and technology to overcome some of our basic biological limits.’

Bostrom’s transhumanism can enhance human performance through existing technologies, such as genetic engineering and information technologies, as well as emerging technologies, such as molecular nanotechnology and intelligence. It does not entail technological optimism, in that he regularly points to the risks of potential harm, including the ‘extreme possibility of intelligent life becoming extinct’ (Bostrom, 2014). In support of Bostrom’s concerns, renowned theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, and billionaire entrepreneur and engineer Elon Musk have issued serious warnings about the potential existential threats to humanity that advances in ‘artificial super-intelligence’ (ASI) may release.

Not all transhumanists are in agreement, nor do they all share Bostrom’s, Hawking’s and Musk’s circumspect views. In David Pearce’s book The Hedonistic Imperative he argues for a biological programme involving genetic engineering and nanotechnology that will ‘eliminate all forms of cruelty, suffering, and malaise’ (Pearce, 1995/2015). Like the shadow side of the ‘progress narrative’ that has been used as an ideology to support racism and ethnic genocide, this sounds frighteningly like a reinvention of Comte and Spencer’s 19th century Social Darwinism. Along similar lines Byron Reese claims in his book Infinite Progress that the Internet and technology will end ‘Ignorance, Disease, Poverty, Hunger and War’ and we will colonise outer space with a billion other planets each populated with a billion people (Reese, 2013). What happens in the meantime to Earth seems of little concern to them.

One of the most extreme forms of transhumanism is posthumanism: a concept connected with the high-tech movement to create so-called machine super-intelligence. Because posthumanism requires technological intervention, posthumans are essentially a new, or hybrid, species, including the cyborg and the android. The movie character Terminator is a cyborg.

The most vocal of high-tech transhumanists have ambitions that seem to have grown out of the superman trope so dominant in early to mid-20th-century North America. Their version of transhumanism includes the idea that human functioning can be technologically enhanced exponentially, until the eventual convergence of human and machine into the singularity (another term for posthumanism). To popularise this concept Google engineer Ray Kurzweil co-founded the Singularity University in Silicon Valley in 2009. While the espoused mission of Singularity University is to use accelerating technologies to address ‘humanity’s hardest problems’, Kurzweil’s own vision is pure science fiction. In another twist, there is a striking resemblance between the Singularity University logo (below upper) and the Superman logo (below lower).

When unleashing accelerating technologies, we need to ask ourselves, how should we distinguish between authentic projects to aid humanity, and highly resourced messianic hubris? A key insight is that propositions put forward by techno-transhumanists are based on an ideology of technological determinism. This means that the development of society and its cultural values are driven by that society’s technology, not by humanity itself.

In an interesting counter-intuitive development, Bostrom points out that since the 1950s there have been periods of hype and high expectations about the prospect of AI (1950s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s) each followed by a period of setback and disappointment that he calls an ‘AI winter’. The surge of hype and enthusiasm about the coming singularity surrounding Kurzweil’s naïve and simplistic beliefs about replicating human consciousness may be about to experience a fifth AI winter.

The Dehumanization Critique

The strongest critiques of the overextension of technology involve claims of dehumanisation, and these arguments are not new. Canadian philosopher of the electronic age Marshall McLuhan cautioned decades ago against too much human extension into technology. McLuhan famously claimed that every media extension of man is an amputation. Once we have a car, we don’t walk to the shops anymore; once we have a computer hard-drive we don’t have to remember things; and with personal GPS on our cell phones no one can find their way without it. In these instances, we are already surrendering human faculties that we have developed over millennia. It is likely that further extending human faculties through techno- and bio-enhancement will lead to arrested development in the natural evolution of higher human faculties.

From the perspective of psychology of intelligence the term artificial intelligence is an oxymoron. Intelligence, by nature, cannot be artificial and its inestimable complexity defies any notion of artificiality. We need the courage to name the notion of ‘machine intelligence’ for what it really is: anthropomorphism. Until AI researchers can define what they mean by intelligence, and explain how it relates to consciousness, the term artificial intelligence must remain a word without universal meaning. At best, so-called artificial intelligence can mean little more than machine capability, which will always be limited by the design and programming of its inventors. As for machine super-intelligence it is difficult not to read this as Silicon Valley hubris.

Furthermore, much of the transhumanist discourse of the 21st century reflects a historical and sociological naïveté. Other than Bostrom, transhumanist writers seem oblivious to the 3,000-year history of humanity’s attempts to predict, control, and understand the future (Gidley, 2017). Although many transhumanists sit squarely within a cornucopian narrative, they seem unaware of the alternating historical waves of techno-utopianism (or Cornucopianism) and techno-dystopianism (or Malthusianism). This is especially evident in their appropriation and hijacking of the term ‘transhumanism’ with little apparent knowledge or regard for its origins.

Origins of a Humanistic Transhumanism

In 1950, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) published the essay From the Pre-Human to the Ultra-Human: The Phases of a Living Planet, in which he speaks of ‘some sort of Trans-Human at the ultimate heart of things’. Teilhard de Chardin’s Ultra-Human and Trans-Human were evolutionary concepts linked with spiritual/human futures. These concepts inspired his friend Sir Julian Huxley to write about transhumanism, which he did in 1957 as follows [Huxley’s italics]:

The human species can, if it wishes, transcend itself—not just sporadically, an individual here in one way, an individual there in another way—but in its entirety, as humanity. We need a name for this new belief. Perhaps transhumanism will serve: man remaining man, but transcending himself, by realising new possibilities of and for his human nature (Huxley, 1957).

Ironically, this quote is used by techno-transhumanists to attribute to Huxley the coining of the term transhumanism. And yet, their use of the term is in direct contradiction to Huxley’s use. Huxley, a biologist and humanitarian, was the first Director-General of UNESCO in 1946, and the first President of the British Humanist Association. His transhumanism was more humanistic and spiritual than technological, inspired by Teilhard de Chardin’s spiritually evolved human. These two collaborators promoted the idea of conscious evolution, which originated with the German romantic philosopher Schelling.

The evolutionary ideas that were in discussion the century before Darwin were focused on consciousness and theories of human progress as a cultural, aesthetic, and spiritual ideal. Late 18th-century German philosophers foreshadowed the 20th-century human potential and positive psychology movements. To support their evolutionary ideals for society they created a universal education system, the aim of which was to develop the whole person (Bildung in German) (Gidley, 2016).

After Darwin, two notable European philosophers began to explore the impact of Darwinian evolution on human futures, in other ways than Spencer’s social Darwinism. Friedrich Nietzsche’s ideas about the higher person (Übermensch) were informed by Darwin’s biological evolution, the German idealist writings on evolution of consciousness, and were deeply connected to his ideas on freedom.

French philosopher Henri Bergson’s contribution to the superhuman discourse first appeared in Creative Evolution (Bergson, 1907/1944). Like Nietzsche, Bergson saw the superman arising out of the human being, in much the same way that humans have arisen from animals. In parallel with the efforts of Nietzsche and Bergson, Rudolf Steiner articulated his own ideas on evolving human-centred futures, with concepts such as spirit self and spirit man (between 1904 and 1925) (Steiner, 1926/1966). During the same period Indian political activist Sri Aurobindo wrote about the Overman who was a type of consciously evolving future human being (Aurobindo, 1914/2000). Both Steiner and Sri Aurobindo founded education systems after the German bildung style of holistic human development.

Consciously Evolving Human-Centred Futures

There are three major bodies of research offering counterpoints to the techno-transhumanist claim that superhuman powers can only be reached through technological, biological, or genetic enhancement. Extensive research shows that humans have far greater capacities across many domains than we realise. In brief, these themes are the future of the body, cultural evolution and futures of thinking.

Michael Murphy’s book The Future of the Body documents ‘superhuman powers’ unrelated to technological or biological enhancement (Murphy, 1992). For forty years Murphy, founder of Esalen Institute, has been researching what he calls a Natural History of Supernormal Attributes. He has developed an archive of 10,000 studies of individual humans, throughout history, who have demonstrated supernormal experiences across twelve groups of attributes. In almost 800 pages Murphy documents the supernormal capacities of Catholic mystics, Sufi ecstatics, Hindi-Buddhist siddhis, martial arts practitioners, and elite athletes. Murphy concludes that these extreme examples are the ‘developing limbs and organs of our evolving human nature’. We also know from the examples of savants, extreme sport and adventure, and narratives of mystics and saints from the vast literature from the perennial philosophies, that we humans have always extended ourselves—often using little more than the power of our minds.

Regarding cultural evolution, numerous 20th century scholars and writers have put forward ideas about human cultural futures. Ervin László links evolution of consciousness with global planetary shifts (László, 2006). Richard Tarnas in The Passion of the Western Mind traces socio-cultural developments over the last 2,000 years, pointing to emergent changes (Tarnas, 1991). Jürgen Habermas suggests a similar developmental pattern in his book Communication and the Evolution of Society (Habermas, 1979). In the late 1990s Duane Elgin and Coleen LeDrew undertook a forty-three-nation World Values Survey, including Scandinavia, Switzerland, Britain, Canada, and the United States. They concluded, ‘a new global culture and consciousness have taken root and are beginning to grow in the world’. They called it the postmodern shift and described it as having two qualities: an ecological perspective and a self-reflexive ability (Elgin & LeDrew, 1997).

In relation to futures of thinking, adult developmental psychologists have built on positive psychology, and the human potential movement beginning with Abraham Maslow’s book Further Reaches of Human Nature (Maslow, 1971). In combination with transpersonal psychology the research is rich with extended views of human futures in cognitive, emotional, and spiritual domains. For four decades, adult developmental psychology researchers such as Michael Commons, Jan Sinnott, and Lawrence Kohlberg have been researching the systematic, pluralistic, complex, and integrated thinking of mature adults (Commons & Ross, 2008; Kohlberg, 1990; Sinnott, 1998). They call this mature thought ‘postformal reasoning’ and their research provides valuable insights into higher modes of reasoning that are central to the discourse on futures of thinking. Features they identify include complex paradoxical thinking, creativity and imagination, relativism and pluralism, self-reflection and ability to dialogue, and intuition. Ken Wilber’s integral psychology research complements his cultural history research to build a significantly enhanced image of the potential for consciously evolving human futures (Wilber, 2000).

I apply these findings to education in my book Postformal Education: A Philosophy for Complex Futures (Gidley, 2016).

Can AI ever cross the Consciousness Threshold?

Given the breadth and subtlety of postformal reasoning, how likely is it that machines could ever acquire such higher functioning human features? The technotopians discussing artificial superhuman intelligence carefully avoid the consciousness question. Bostrom explains that all the machine intelligence systems currently in use operate in a very narrow range of human cognitive capacity (weak AI). Even at its most ambitious, it is limited to trying to replicate ‘abstract reasoning and general problem-solving skills’ (strong AI). In spite of all the hype around AI and ASI, the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI)’s own website states that even ‘human-equivalent general intelligence is still largely relegated to the science fiction shelf.’ Regardless of who writes about posthumanism, and whether they are Oxford philosophers, MIT scientists, or Google engineers, they do not yet appear to be aware that there are higher forms of human reasoning than their own. Nor do they have the scientific and technological means to deliver on their high-budget fantasies. Machine super-intelligence is not only an oxymoron, but a science fiction concept.

Even if techno-developers were to succeed in replicating general intelligence (strong AI), it would only function at the level of Piaget’s formal operations. Yet adult developmental psychologists have shown that mature, high-functioning adults are capable of very complex, imaginative, integrative, paradoxical, spiritual, intuitive wisdom—just to name a few of the qualities we humans can consciously evolve. These complex postformal logics go far beyond the binary logic used in coding and programming machines, and it seems also far beyond the conceptual parameters of the AI programmers themselves. I find no evidence in the literature that anyone working with AI is aware of either the limits of formal reasoning or the vast potential of higher stages of postformal reasoning. In short, ASI proponents are entrapped in their thin cybernetic view of intelligence. As such they are oblivious to the research on evolution of consciousness, metaphysics of mind, multiple intelligences, philosophy and psychology of consciousness, transpersonal psychology and wisdom studies, all providing ample evidence that human intelligence is highly complex and evolving.

When all of this research is taken together it indicates that we humans are already capable of far greater powers of mind, emotion, body, and spirit than previously imagined. If we seriously want to develop superhuman intelligence and powers in the 21st century and beyond we have a choice. We can continue to invest heavily in naïve technotopian dreams of creating machines that can operate better than humans. Or we can invest more of our consciousness, energy, and resources on educating and consciously evolving human futures with all the wisdom that would entail.

About Professor Jennifer M. Gidley PhD

Author, psychologist, educator and futurist, Jennifer is a global thought leader and advocate for human-centred futures in an era of hi-tech hype and hubris. She is Adjunct Professor at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, UTS, Sydney and author of The Future: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2017) and Postformal Education: A Philosophy for Complex Futures (Springer, 2016). As former President of the World Futures Studies Federation (2009−2017), a UNESCO and UN ECOSOC partner and global peak body for futures studies, Jennifer led a network of hundreds of the world’s leading futures scholars and researchers from over 60 countries for eight years.

References

[To check references please go to original article in Paradigm Explorer, p. 15–18]