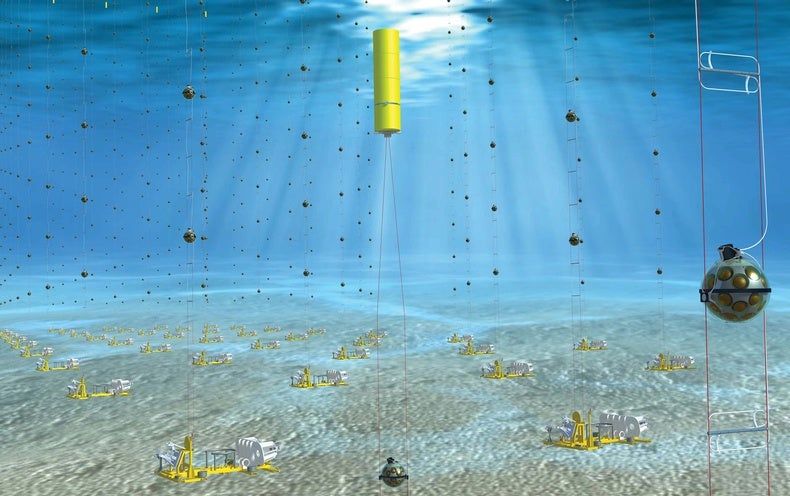

Submarine neutrino detectors will hunt for dark matter, distant star explosions, and more.

O,.,o.

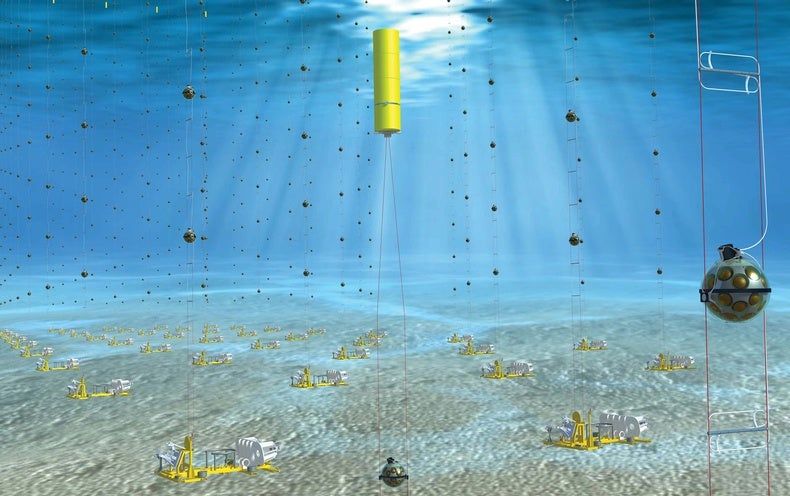

In the far reaches of the Universe, astronomers have managed to capture a rare interaction. As a supermassive black hole ravenously slurps down matter around it, it’s sending out jets of plasma — pushing into and heating the gas in the galaxy around it.

This is difficult to capture at the best of times, but this case was a particularly impressive feat. The galaxy in question is a whopping 11 billion light-years away — when the Universe was less than 3 billion years old.

It’s called MG J0414+0534, and astronomers managed to capture it in detail because of gravitational lensing. In between us and the galaxy is a different, rather massive galaxy whose gravity distorts the path of the light travelling from behind it, creating four images of MG J0414+0534 around it (see image below).

Circa 2006

By Maggie Mckee

Nearly all of the information that falls into a black hole escapes back out, a controversial new study argues. The work suggests that black holes could one day be used as incredibly accurate quantum computers – if enormous theoretical and practical hurdles can first be overcome.

Black holes are thought to destroy anything that crosses a point of no return around them called an “event horizon”. But in the 1970s, Stephen Hawking used quantum mechanics to show black holes do emit radiation, which eventually evaporates them away completely.

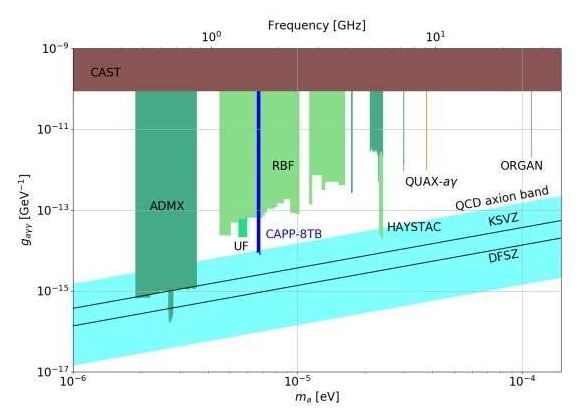

Researchers at the Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research (CAPP), within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS, South Korea), have reported the first results of their search of axions, elusive, ultra-lightweight particles that are considered dark matter candidates. IBS-CAPP is located at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST). Published in Physical Review Letters, the analysis combines data taken over three months with a new axion-hunting apparatus developed over the last two years.

Proving the existence of axions could solve two of the biggest mysteries in modern physics at once: why galaxies orbiting within galaxy clusters are moving far faster than expected, and why two fundamental forces of nature follow different symmetry rules. The first conundrum was raised back in the 1930s, and was confirmed in the 1970s when astronomers noticed that the observed mass of the Milky Way galaxy could not explain the strong gravitational pull experienced by the stars in the galaxies. The second enigma, known as the strong CP problem, was dubbed by Forbes magazine as “the most underrated puzzle in all of physics” in 2019.

Symmetry is an important element of particle physics and CP refers to the Charge+Parity symmetry, where the laws of physics are the same if particles are interchanged with their corresponding antiparticles © in their mirror images ℗. In the case of the strong force, which is responsible for keeping nuclei together, CP violation is allowed theoretically, but has never been detected, even in the most sensitive experiments. On the other hand, CP symmetry is violated both theoretically and experimentally in the weak force, which underlies some types of radioactive decays. In 1977, theoretical physicists Roberto Peccei and Helen Quinn proposed the Peccei-Quinn symmetry as a theoretical solution to this problem, and two Nobel laureates in Physics, Frank Wilczek and Steven Weinberg, showed that the Peccei-Quinn symmetry results in a new particle: the axion. The particle was named after an American detergent, because it should clean the strong interactions mess.

I think these can be fought with current technology such as quantum radar even other higher level technology. It can also be hacked with quantum radar or neutrino beams.

Know colloquially as the “Black Holes” by the U.S. Navy, the Improved-Kilo-class of submarines are quite deadly — and could turn the balance of power in the South China Sea in China’s favor.

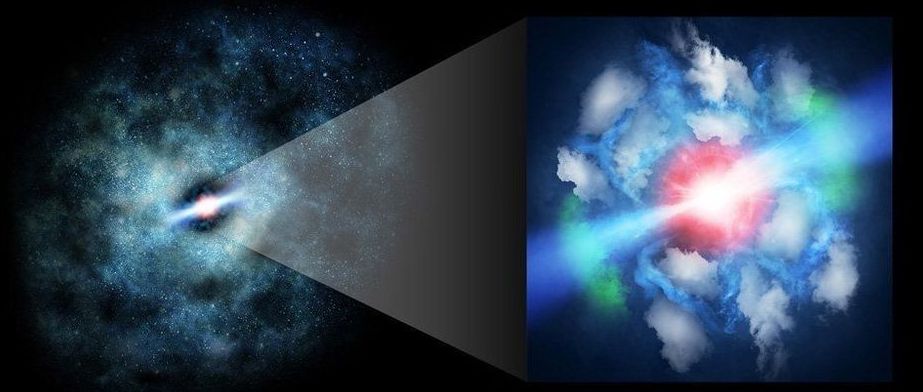

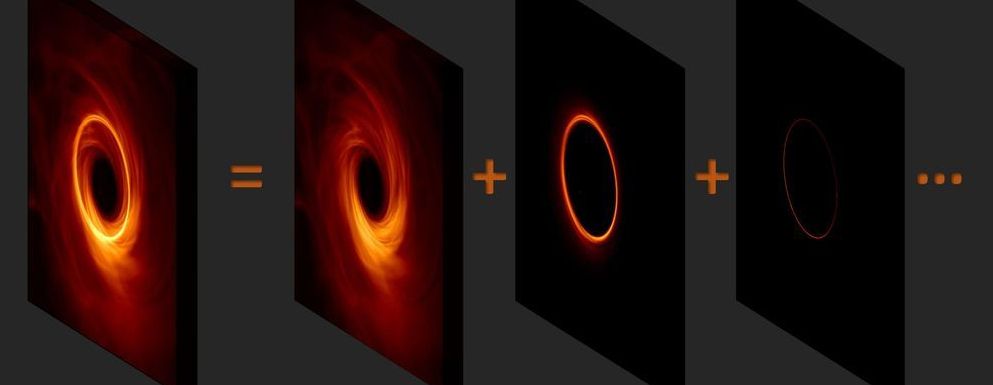

Last April, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) sparked international excitement when it unveiled the first image of a black hole. Today, a team of researchers have published new calculations that predict a striking and intricate substructure within black hole images from extreme gravitational light bending.

“The image of a black hole actually contains a nested series of rings,” explains Michael Johnson of the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard and Smithsonian (CfA). “Each successive ring has about the same diameter but becomes increasingly sharper because its light orbited the black hole more times before reaching the observer. With the current EHT image, we’ve caught just a glimpse of the full complexity that should emerge in the image of any black hole.”

Because black holes trap any photons that cross their event horizon, they cast a shadow on their bright surrounding emission from hot infalling gas. A “photon ring” encircles this shadow, produced from light that is concentrated by the strong gravity near the black hole. This photon ring carries the fingerprint of the black hole—its size and shape encode the mass and rotation or “spin” of the black hole. With the EHT images, black hole researchers have a new tool to study these extraordinary objects.

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute; AEI) in Hannover together with international colleagues have published their second Open Gravitational-wave Catalog (2-OGC). They used improved search methods to dig deeper into publicly available data from LIGO’s and Virgo’s first and second observation runs. Apart from confirming the ten known binary black hole mergers and one binary neutron star merger, they also identify four promising black hole merger candidates, which were missed by initial LIGO/Virgo analyses. These results demonstrate the value of searches in public LIGO/Virgo data by research groups independent of the LIGO/Virgo collaborations. The research team also makes available its complete catalogue in addition to detailed analysis of more than a dozen possible binary black hole mergers.

“We incorporate cutting edge methods,” says Alexander Nitz, a staff scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute) in Hannover, who led the international research team. “Our improvements enable discovering fainter binary black hole mergers: the four additional signals show that this works!”

The results were published in The Astrophysical Journal today.