O.,o wut!

A key signal for a certain kind of dark matter failed to turn up in a search throughout the Milky Way. Now scientists are disagreeing about what that means.

Education Saturday with Curious Droid.

Far from calm and peaceful, space is a dangerous place with high levels of radiation not only from our sun but from distant supernovas. This is not only dangerous to us but also to the spacecraft themselves with is able to damage the electronics and computers that keep it running and the crew alive in it. So how do they protect the craft and crew with what looks like almost no shielding at all?

This video is sponsored my Magellan TV. https://try.magellantv.com/curiousdroid

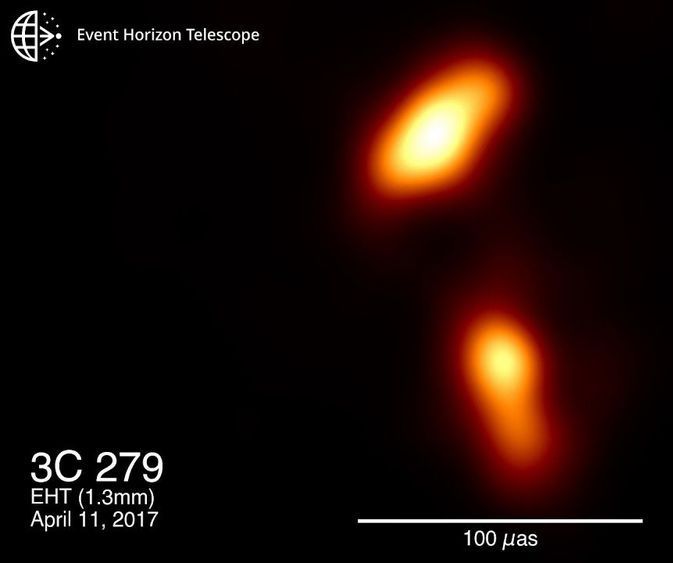

Last year, a global collaboration of scientists made history by unveiling the very first direct image of a black hole. Now, we have a magnificent follow-up — the closest-ever look at a violent jet spewed forth by a supermassive black hole.

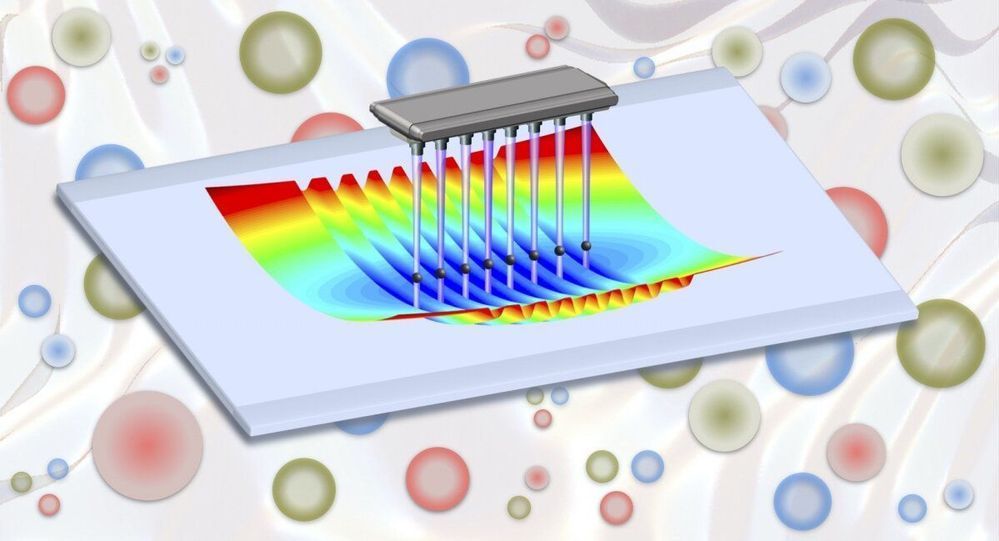

In nuclear physics, like much of science, detailed theories alone aren’t always enough to unlock solid predictions. There are often too many pieces, interacting in complex ways, for researchers to follow the logic of a theory through to its end. It’s one reason there are still so many mysteries in nature, including how the universe’s basic building blocks coalesce and form stars and galaxies. The same is true in high-energy experiments, in which particles like protons smash together at incredible speeds to create extreme conditions similar to those just after the Big Bang.

Fortunately, scientists can often wield simulations to cut through the intricacies. A simulation represents the important aspects of one system—such as a plane, a town’s traffic flow or an atom—as part of another, more accessible system (like a computer program or a scale model). Researchers have used their creativity to make simulations cheaper, quicker or easier to work with than the formidable subjects they investigate—like proton collisions or black holes.

Simulations go beyond a matter of convenience; they are essential for tackling cases that are both too difficult to directly observe in experiments and too complex for scientists to tease out every logical conclusion from basic principles. Diverse research breakthroughs—from modeling the complex interactions of the molecules behind life to predicting the experimental signatures that ultimately allowed the identification of the Higgs boson—have resulted from the ingenious use of simulations.

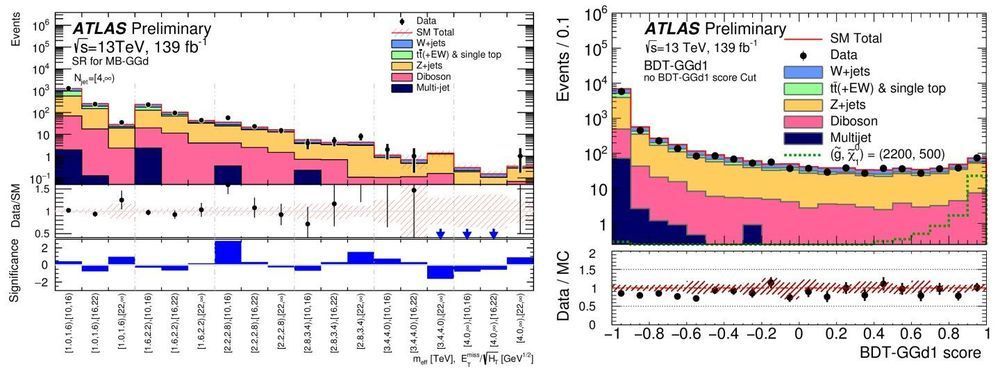

New particles sensitive to the strong interaction might be produced in abundance in the proton-proton collisions generated by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) – provided that they aren’t too heavy. These particles could be the partners of gluons and quarks predicted by supersymmetry (SUSY), a proposed extension of the Standard Model of particle physics that would expand its predictive power to include much higher energies. In the simplest scenarios, these “gluinos” and “squarks” would be produced in pairs, and decay directly into quarks and a new stable neutral particle (the “neutralino”), which would not interact with the ATLAS detector. The neutralino could be the main constituent of dark matter.

The ATLAS Collaboration has been searching for such processes since the early days of LHC operation. Physicists have been studying collision events featuring “jets” of hadrons, where there is a large imbalance in the momenta of these jets in the plane perpendicular to the colliding protons (“missing transverse momentum,” ETmiss). This missing momentum would be carried away by the undetectable neutralinos. So far, ATLAS searches have led to increasingly tighter constraints on the minimum possible masses of squarks and gluinos.

Is it possible to do better with more data? The probability of producing these heavy particles decreases exponentially with their masses, and thus repeating the previous analyses with a larger dataset only goes so far. New, sophisticated methods that help to better distinguish a SUSY signal from the background Standard Model events are needed to take these analyses further. Crucial improvements may come from increasing the efficiency for selecting signal events, improving the rejection of background processes, or looking into less-explored regions.

Adilson Motter, Northwestern University

After 12 successful seasons, “The Big Bang Theory” has finally come to a fulfilling end, concluding its reign as the longest running multicamera sitcom on TV.

If you’re one of the few who haven’t seen the show, this CBS series centers around a group of young scientists defined by essentially every possible stereotype about nerds and geeks. The main character, Sheldon (Jim Parsons), is a theoretical physicist. He is exceptionally intelligent, but also socially unconventional, egocentric, envious and ultra-competitive. His best friend, Leonard (Johnny Galecki), is an experimental physicist who, although more balanced, also shows more fluency with quantum physics than with ordinary social situations.

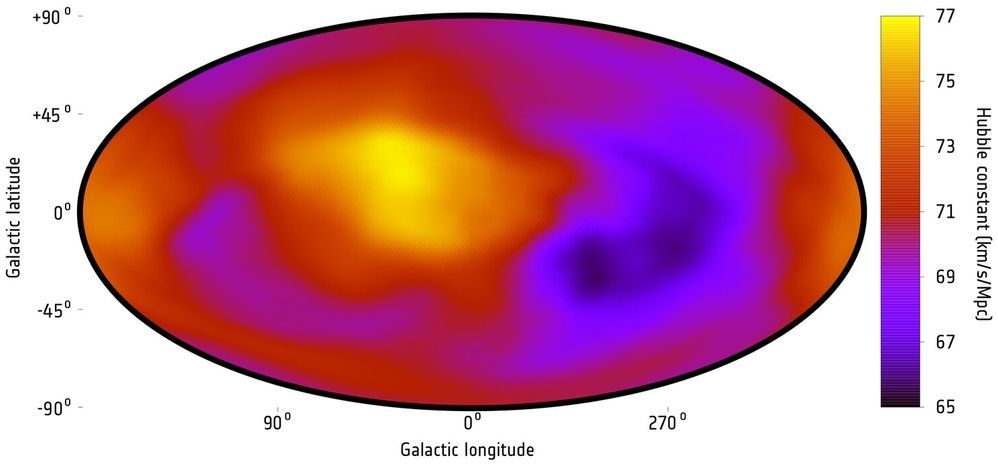

(8 April 2020 — ESA) Astronomers have assumed for decades that the Universe is expanding at the same rate in all directions. A new study based on data from ESA’s XMM-Newton, NASA’s Chandra and the German-led ROSAT X-ray observatories suggests this key premise of cosmology might be wrong.

Konstantinos Migkas, a PhD researcher in astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Bonn, Germany, and his supervisor Thomas Reiprich originally set out to verify a new method that would enable astronomers to test the so-called isotropy hypothesis. According to this assumption, the Universe has, despite some local differences, the same properties in each direction on the large scale.

Widely accepted as a consequence of well-established fundamental physics, the hypothesis has been supported by observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB). A direct remnant of the Big Bang, the CMB reflects the state of the Universe as it was in its infancy, at only 380 000 years of age. The CMB’s uniform distribution in the sky suggests that in those early days the Universe must have been expanding rapidly and at the same rate in all directions.

This could help save a universe or reality someday.

The smartest kid of just 13 years old has managed to prove that the CERN recently destroyed our Universe, shifting us into a completely another parallel and alternate dimension.

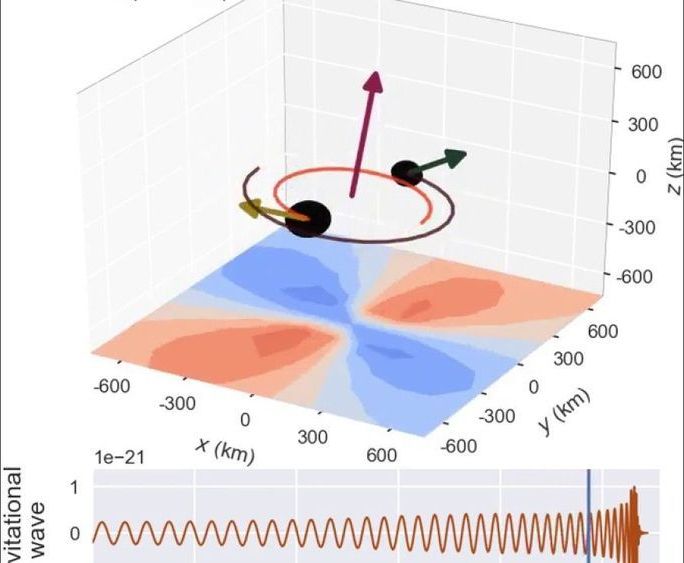

Shoot a rifle, and the recoil might knock you backward. Merge two black holes in a binary system, and the loss of momentum gives a similar recoil—a “kick”—to the merged black hole.

“For some binaries, the kick can reach up to 5000 kilometers a second, which is larger than the escape velocity of most galaxies,” said Vijay Varma, an astrophysicist at the California Institute of Technology and an incoming inaugural Klarman Fellow at Cornell University’s College of Arts & Sciences.

Varma and his fellow researchers have developed a new method using gravitational wave measurements to predict when a final black hole will remain in its host galaxy and when it will be ejected. Such measurements could provide a crucial missing piece of the puzzle behind the origin of heavy black holes, said Varma, as well as offer insights into galaxy evolution and tests of general relativity. He is lead author of “Extracting the Gravitational Recoil from Black Hole Merger Signals,” published March 13 in Physical Review Letters and co-authored with Maximiliano Isi and Sylvia Biscoveanu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

A long-held mystery in the field of nuclear physics is why the universe is composed of the specific materials we see around us. In other words, why is it made of “this” stuff and not other stuff?

Specifically of interest are the physical processes responsible for producing heavy elements—like gold, platinum and uranium—that are thought to happen during neutron star mergers and explosive stellar events.

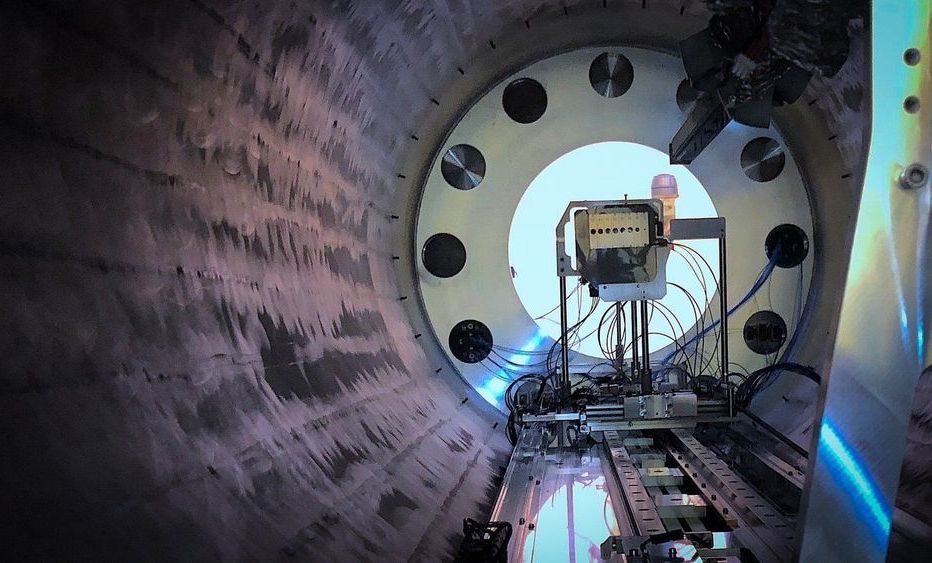

Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory led an international nuclear physics experiment conducted at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, that utilizes novel techniques developed at Argonne to study the nature and origin of heavy elements in the universe. The study may provide critical insights into the processes that work together to create the exotic nuclei, and it will inform models of stellar events and the early universe.