Physicists have discovered a special kind of particle can exist around a pair of black holes in a similar way as an electron can exist around a pair of hydrogen atoms — the first example of a “gravitational molecule.”

When we apprehend reality as the entirety of everything that exists including all dimensionality, all events and entities in their respective timelines, then by definition nothing exists outside of reality, not even “nothing.” It means that the first cause for reality’s existence must lie within ontological reality itself, since there is nothing outside of it. This self-causation of reality is perhaps best understood in relation to the existence of your own mind. Self-simulated reality transpires as self-evident when you relate to the notion that a phenomenal mind, which is a web of patterns, conceives a certain novel pattern and simultaneously perceives it. Furthermore, the imminent natural God of Spinoza, or Absolute Consciousness, becomes intelligible by applying a scientific tool of extrapolation to the meta-systemic phenomenon of radical emergence and treating consciousness as a primary ontological mover, the Source if you will, not a by-product of material interactions.

#OntologicalHolism #ontology #holism #cosmology #phenomenology #consciousness #mind #evolution

So the Universe is getting hotter? 😃

For almost a century, astronomers have understood that the Universe is in a state of expansion. Since the 1990s, they have come to understand that as of 4 billion years ago, the rate of expansion has been speeding up.

As this progresses, and the galaxy clusters and filaments of the Universe move farther apart, scientists theorize that the mean temperature of the Universe will gradually decline.

But according to new research led by the Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics (CCAPP) at Ohio State University, it appears that the Universe is actually getting hotter as time goes on.

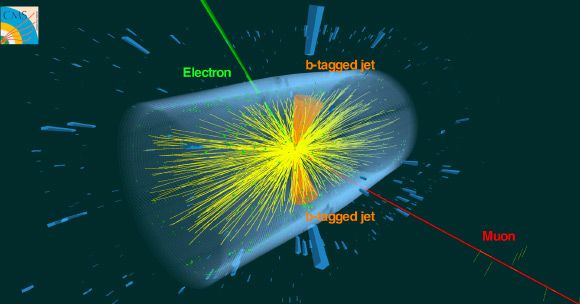

New results from the CMS Collaboration at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider demonstrate for the first time that top quarks are produced in nucleus-nucleus collisions. The results open the path to study in a new and unique way the extreme state of matter that is thought to have existed shortly after the Big Bang.

First observed in proton-antiproton collisions at the Tevatron collider 25 years ago, this particle is also a unique and potentially very powerful tool to understand the inner content of nuclear matter.

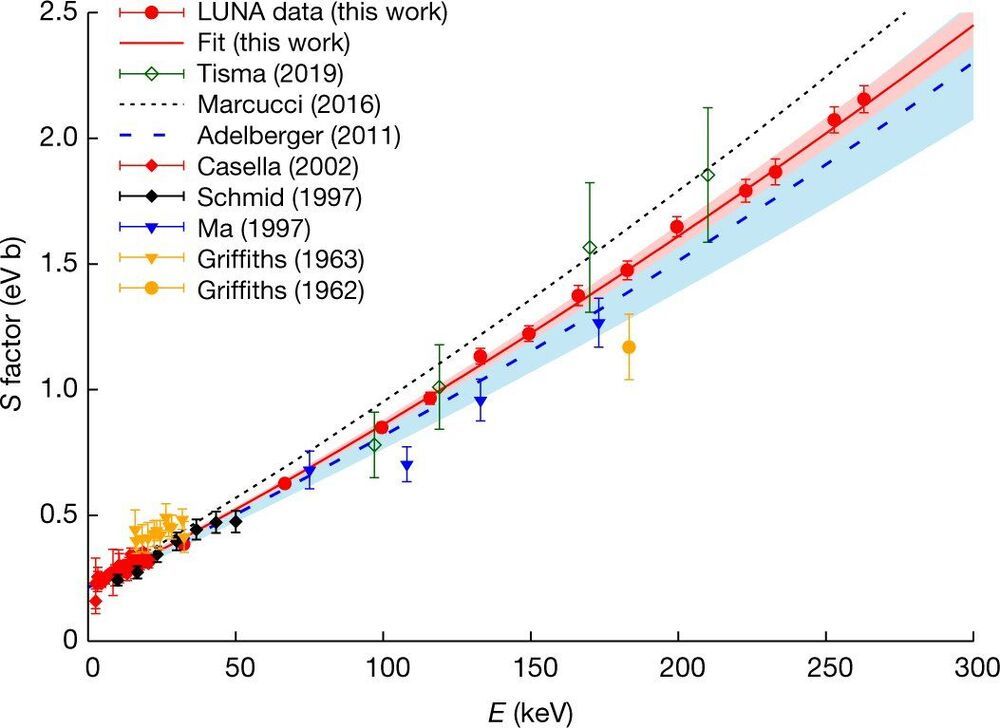

A large team of researchers affiliated with a host of institutions in Italy, the U.K and Hungary has carried out the most precise measurements yet of deuterium fusing with a proton to form helium-3. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the group describes their effort and how they believe it will contribute to better understanding the events that transpired during the first few minutes after the Big Bang.

Astrophysics theory suggests that the creation of deuterium was one of the first things that happened after the Big Bang. Therefore, it plays an important role in Big Bang nucleosynthesis—the reactions that happened afterward that led to the production of several of the light elements. Theorists have developed equations that show the likely series of events that occurred, but to date, it has been difficult to prove them correct without physical evidence. In this new effort, the researchers working at the Laboratory for Underground Nuclear Astrophysics in Italy have carried out experiments to simulate those first few minutes, hoping to confirm the theories.

The work was conducted deep under the thick rock cover of the Gran Sasso mountain to prevent interference from cosmic rays —it involved firing a beam of protons at a deuterium target—deuterium being a form of hydrogen with just one proton and one neutron—and then measuring the rate of fusion. But because the rate of fusion is so low, the bombardment had to be carried out many times—the team carried out their work nearly every weekend for three years.

A new study lead by GSI scientists and international colleagues investigates black-hole formation in neutron star mergers. Computer simulations show that the properties of dense nuclear matter play a crucial role, which directly links the astrophysical merger event to heavy-ion collision experiments at GSI and FAIR. These properties will be studied more precisely at the future FAIR facility. The results have now been published in Physical Review Letters. With the award of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for the theoretical description of black holes and for the discovery of a supermassive object at the center of our galaxy, the topic currently also receives a lot of attention.

But under which conditions does a black hole actually form? This is the central question of a study lead by the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung in Darmstadt within an international collaboration. Using computer simulations, the scientists focus on a particular process to form black holes namely the merging of two neutron stars.

Neutron stars consists of highly compressed dense matter. The mass of one and a half solar masses is squeezed to the size of just a few kilometers. This corresponds to similar or even higher densities than in the inner of atomic nuclei. If two neutron stars merge, the matter is additionally compressed during the collision. This brings the merger remnant on the brink to collapse to a black hole. Black holes are the most compact objects in the universe, even light cannot escape, so these objects cannot be observed directly.

The finding marks a major breakthrough in a search of almost 20 years, carried out in particle physics labs all over the world.

To understand what a tetraquark is and why the discovery is important, we need to step back in time to 1964, when particle physics was in the midst of a revolution. Beatlemania had just exploded, the Vietnam war was raging and two young radio astronomers in New Jersey had just discovered the strongest evidence ever for the Big Bang theory.

On the other side of the U.S., at the California Institute of Technology, and on the other side of the Atlantic, at CERN in Switzerland, two particle physicists were publishing two independent papers on the same subject. Both were about how to make sense of the enormous number of new particles that had been discovered over the past two decades.

We probably think we know gravity pretty well. After all, we have more conscious experience with this fundamental force than with any of the others (electromagnetism and the weak and strong nuclear forces). But even though physicists have been studying gravity for hundreds of years, it remains a source of mystery.

In our video Why Is Gravity Different? We explore why this force is so perplexing and why it remains difficult to understand how Einstein’s general theory of relativity (which covers gravity) fits together with quantum mechanics.

Gravity is extraordinarily weak and nearly impossible to study directly at the quantum level. We cannot scrutinize it using particle accelerators like we can with the other forces, so we need other ways to get at quantum gravity.

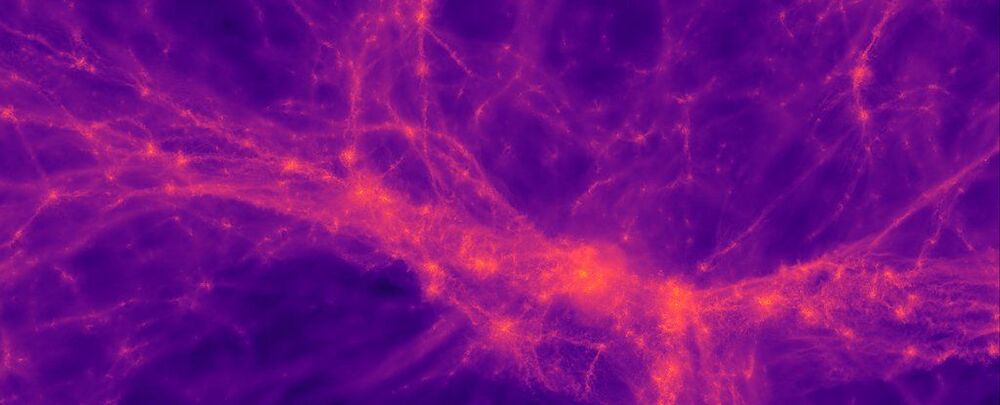

The gravitational force in the Universe under which it has evolved from a state almost uniform at the Big Bang until now, when matter is concentrated in galaxies, stars and planets, is provided by what is termed ‘dark matter.’ But in spite of the essential role that this extra material plays, we know almost nothing about its nature, behavior and composition, which is one of the basic problems of modern physics. In a recent article in Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters, scientists at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC)/University of La Laguna (ULL) and of the National University of the North-West of the Province of Buenos Aires (Junín, Argentina) have shown that the dark matter in galaxies follows a ‘maximum entropy’ distribution, which sheds light on its nature.

Dark matter makes up 85% of the matter of the Universe, but its existence shows up only on astronomical scales. That is to say, due to its weak interaction, the net effect can only be noticed when it is present in huge quantities. As it cools down only with difficulty, the structures it forms are generally much bigger than planets and stars. As the presence of dark matter shows up only on large scales the discovery of its nature probably has to be made by astrophysical studies.