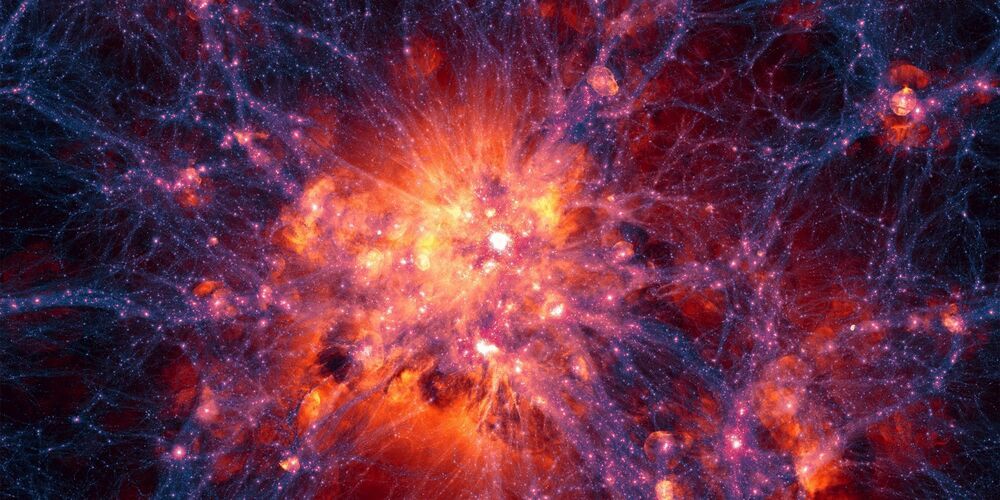

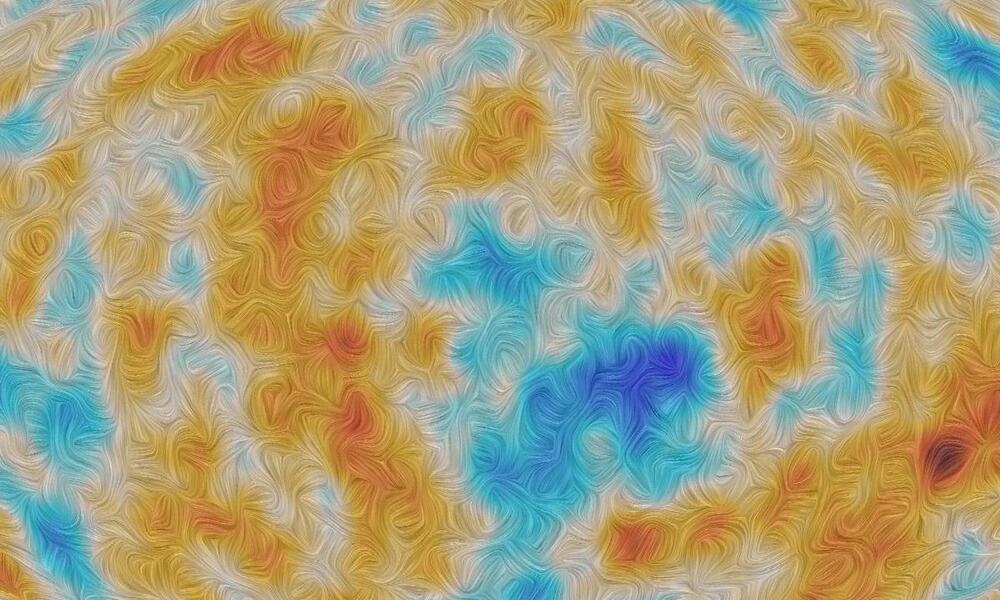

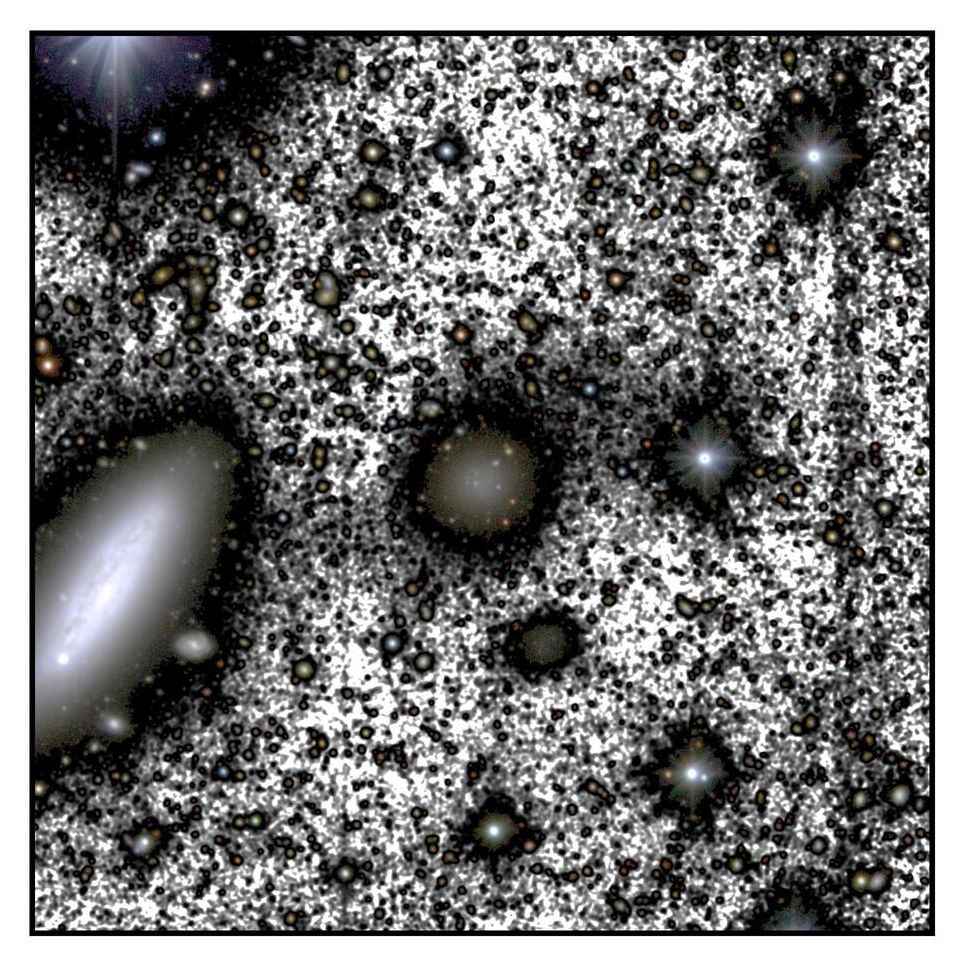

Images from the Survey of the MAgellanic Stellar History (SMASH) reveal a striking family portrait of our galactic neighbors—the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. The images represent a portion of the second data release from the deepest, most extensive survey of the Magellanic Clouds. The observations consist of roughly 4 billion measurements of 360 million objects.

A sprawling portrait of two astronomical galactic neighbors presents a new perspective on the swirls of stars, gas, and dust making up the nearby dwarf galaxies known as the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds—a pair of dwarf satellite galaxies to our Milky Way. While this isn’t the first survey to map these nearby cosmic siblings—the Survey of the MAgellanic Stellar History (SMASH) is the most extensive survey yet.

The international team of astronomers responsible for the observations used the 520-megapixel high-performance Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile. These data are now available to astronomers worldwide through Astro Data Lab at NOIRLab’s Community Science and Data Center (CSDC). CTIO and CSDC are both Programs of NSF’s NOIRLab.