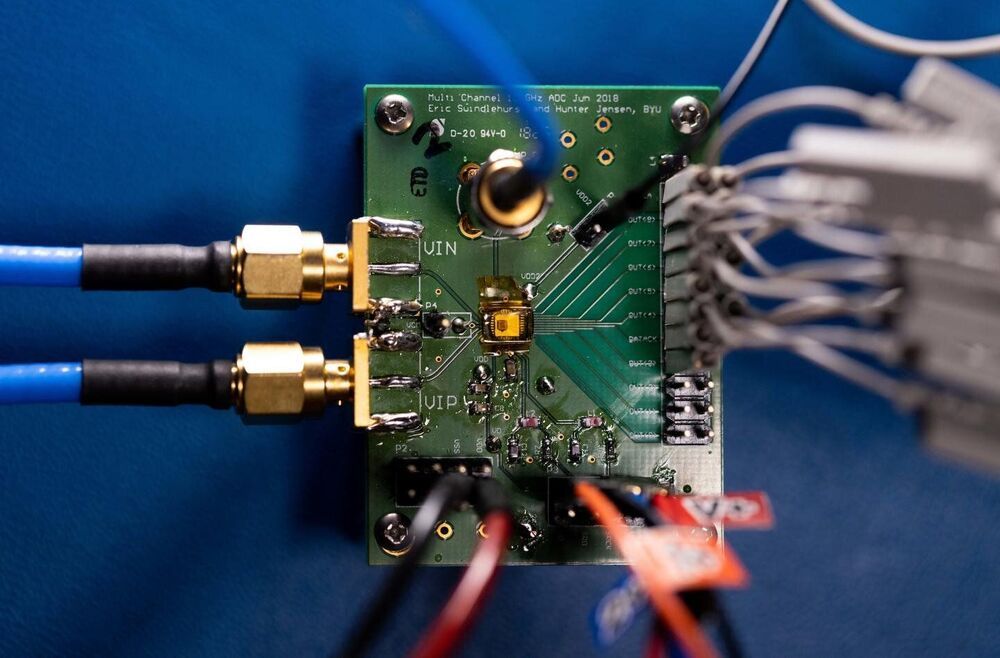

Seagate has been working toward developing a dual-actuator hard drive, meaning that the drive will contain two sets of independently controlled read/write heads. Now, after several years, the company has released its first functional dual-actuator hard drive, the Mach.2. Currently, only enterprises can purchase and use this product, meaning that at least for now, end users will have to wait their turn.

So far, Seagate has reported the Mach.2’s sequential, sustained transfer rate as up to 524MBps—over double the rate of a fast but generic rust disk, closer to the capacity seen in SATA SSD. In fact, this increased transfer rate carries over into input/output as well, featuring 304 IOPS read / 384 IOPS write and only 4.16 ms average latency. By contrast, normal hard drives usually run at 100/150 IOPS with about the same average latency.

Of course, all of that extra capacity requires additional power. Even while idle, the Mach.2 runs at 7.2 W, while Seagate’s standard Ironwolf line runs at 5 W while idle. That said, it is a bit easier to measure the power specs of Mach.2 than Ironwolf, as the former’s power use can be determined using several random input/output scenarios, as opposed to Ironwolf, whose power is gauged from its “average operating power,” a metric undefined by the Seagate data sheet reference.