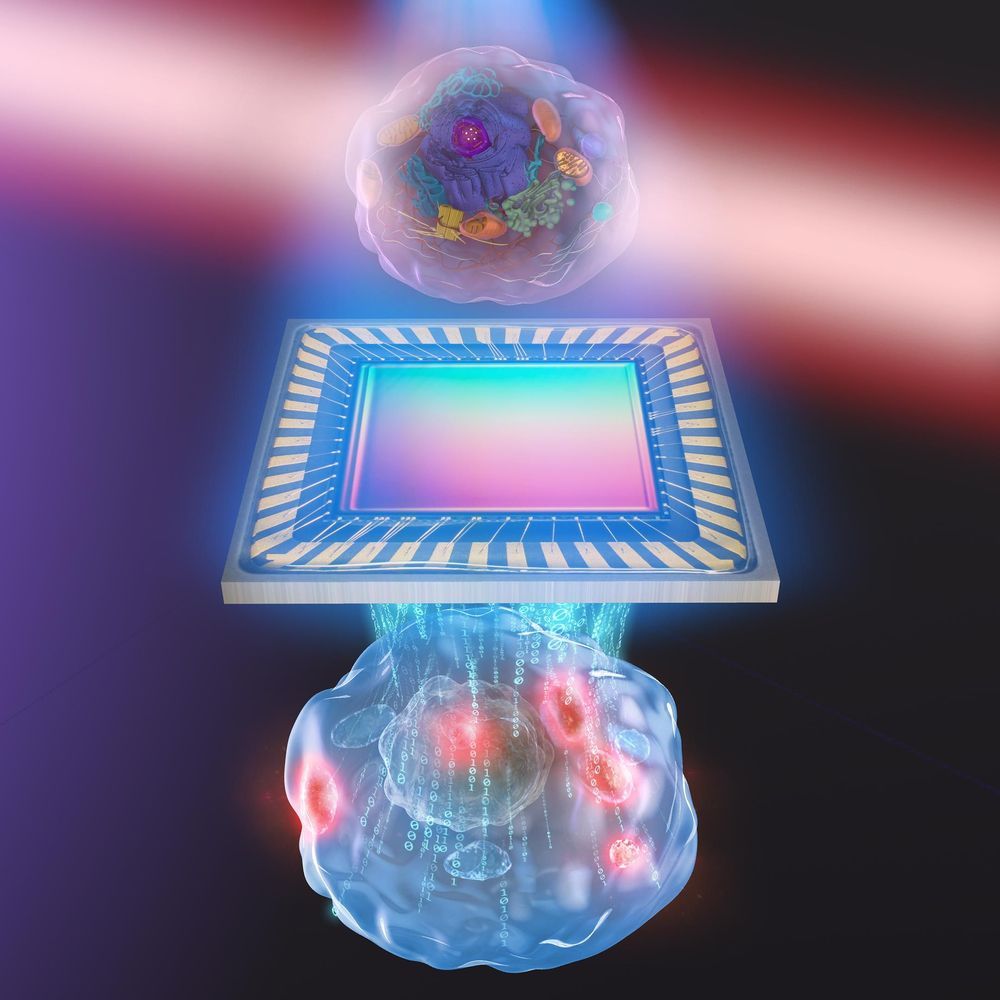

No damage caused by strong light, no artificial dyes or fluorescent tags needed.

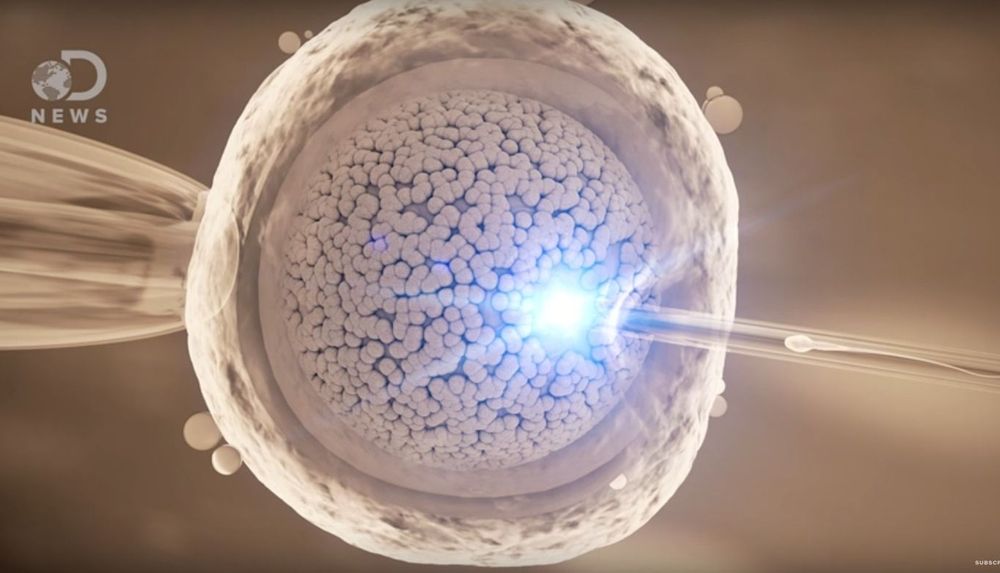

The insides of living cells can be seen in their natural state in greater detail than ever before using a new technique developed by researchers in Japan. This advance should help reveal the complex and fragile biological interactions of medical mysteries, like how stem cells develop or how to deliver drugs more effectively.

“Our system is based on a simple concept, which is one of its advantages,” said Associate Professor Takuro Ideguchi from the University of Tokyo Research Institute for Photon Science and Technology. The results of Ideguchi’s team were published recently in Optica, the Optical Society’s research journal.