A personal, handheld device emitting high-intensity ultraviolet light to disinfect areas by killing the novel coronavirus is now feasible, according to researchers at Penn State, the University of Minnesota and two Japanese universities.

There are two commonly employed methods to sanitize and disinfect areas from bacteria and viruses—chemicals or ultraviolet radiation exposure. The UV radiation is in the 200 to 300 nanometer range and known to destroy the virus, making the virus incapable of reproducing and infecting. Widespread adoption of this efficient UV approach is much in demand during the current pandemic, but it requires UV radiation sources that emit sufficiently high doses of UV light. While devices with these high doses currently exist, the UV radiation source is typically an expensive mercury-containing gas discharge lamp, which requires high power, has a relatively short lifetime, and is bulky.

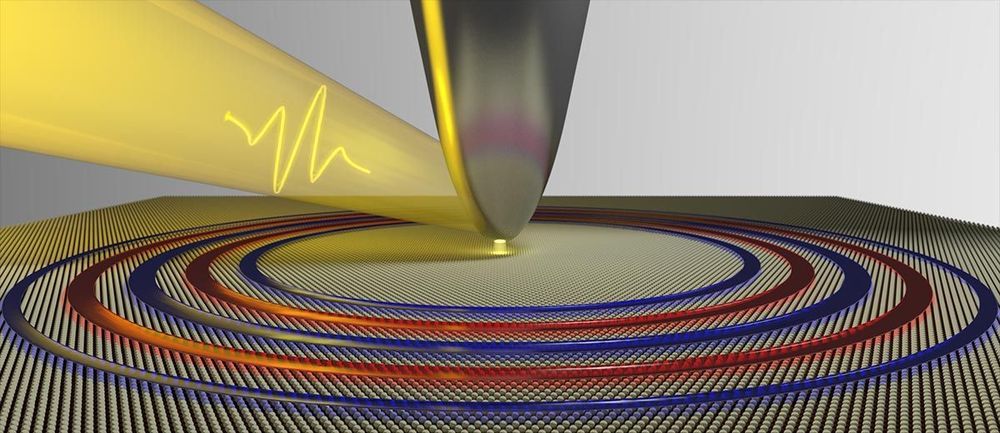

The solution is to develop high-performance, UV light emitting diodes, which would be far more portable, long-lasting, energy efficient and environmentally benign. While these LEDs exist, applying a current to them for light emission is complicated by the fact that the electrode material also has to be transparent to UV light.