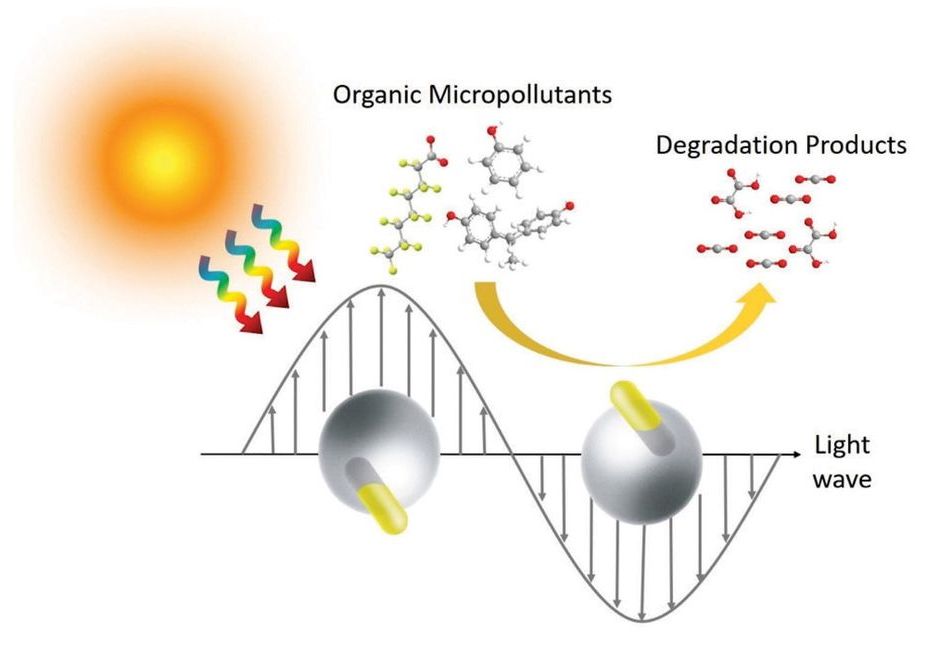

As part of their studies, the scientists also examined the mechanisms by which some of the modified drugs were altered by the cultured microbiomes. To understand exactly how the transformations occurred, they traced the source of the chemical transformations to particular bacterial species and to genes within those bacteria. They also showed that microbiome-derived metabolic reactions discoverable using their approach could be recapitulated in a mouse model, which is the first step in adapting the approach for human drug development.

The framework could feasibly be used to aid drug discovery by identifying potential drug-microbiome interactions early in development, and so inform on formulation changes. It could also be used during clinical trials to better analyze drug toxicity and efficacy, and be harnessed to help personalize treatment to the microbiome of each patient. This could help to predict how a certain drug will behave, and suggest changes to the therapeutic strategy if undesired effects are predicted. “Our framework identifies novel drug-microbiome interactions that vary between individuals and demonstrates how the gut microbiome might be used in drug development and personalized medicine,” the team concluded.

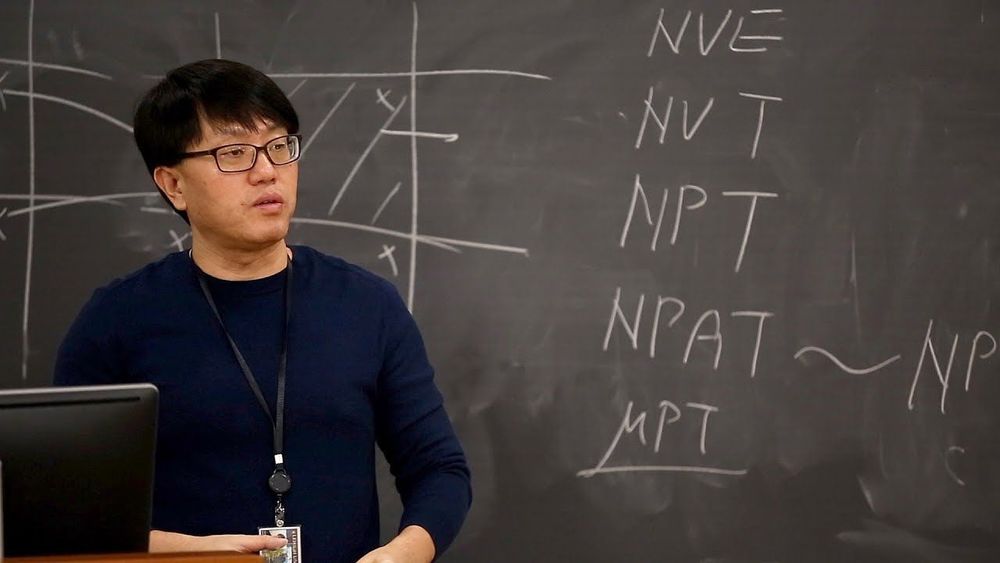

“This is a case where medicine and ecology collide,” said Jaime Lopez, a graduate student in the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics and a co-first author on the study, who contributed the computational and quantitative analysis of the data. “The bacteria in these microbial communities help each other survive, and they influence each other’s enzymatic profiles. This is something you would never capture if you didn’t study it in a community.”

Researchers at Princeton University have developed a way of systematically evaluating how the microbial communities in our intestines can chemically transform, or metabolize, drugs that are taken orally, in ways that impact on their efficacy and potentially safety. The new methodology—which the team used to evaluate the gut microbiome’s effect on hundreds of common medications already on the market—provides a more complete picture of how gut bacteria metabolize drugs. The framework could also feasibly help in the development of drugs that are more effective, have fewer side effects, and are personalized to an individual’s microbiome.

Previous studies have examined how single species of gut bacteria can metabolize oral medications, but the new framework enables evaluation of a person’s entire intestinal microbial community. “Basically, we do not run and hide from the complexity of the microbiome, but instead, we embrace it,” said Mohamed S. Donia, PhD, assistant professor of molecular biology. “This approach allows us to gain a holistic and more realistic view of the microbiome’s contribution to drug metabolism.”

Donia and colleagues reported on their findings in Cell, in a paper titled, “Personalized Mapping of Drug Metabolism by the Human Gut Microbiome.”