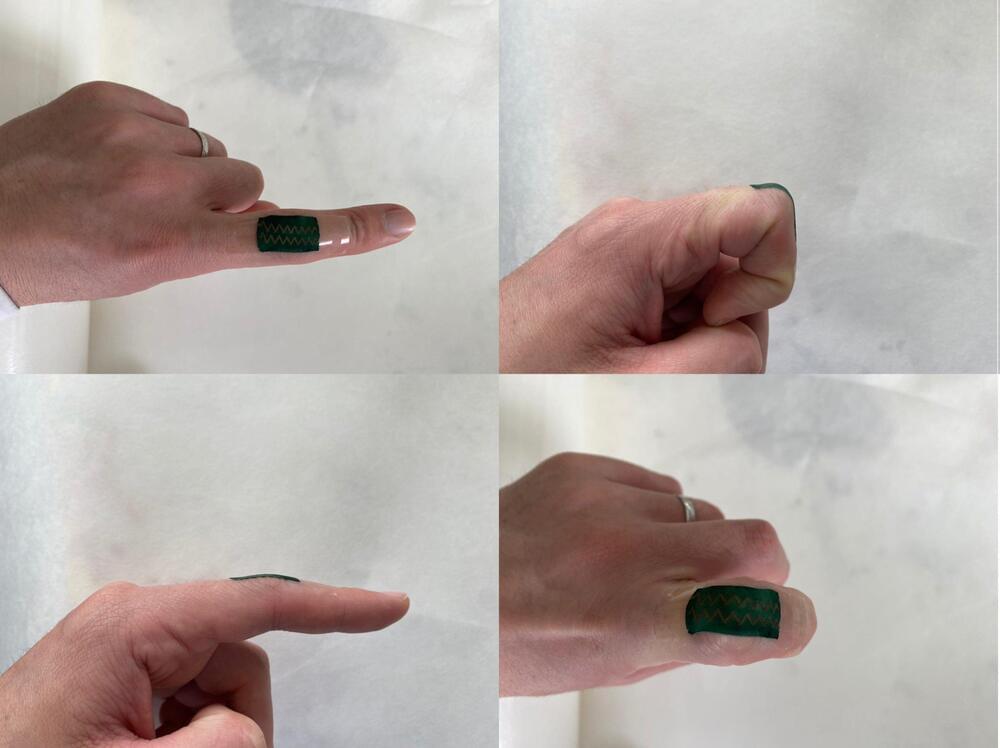

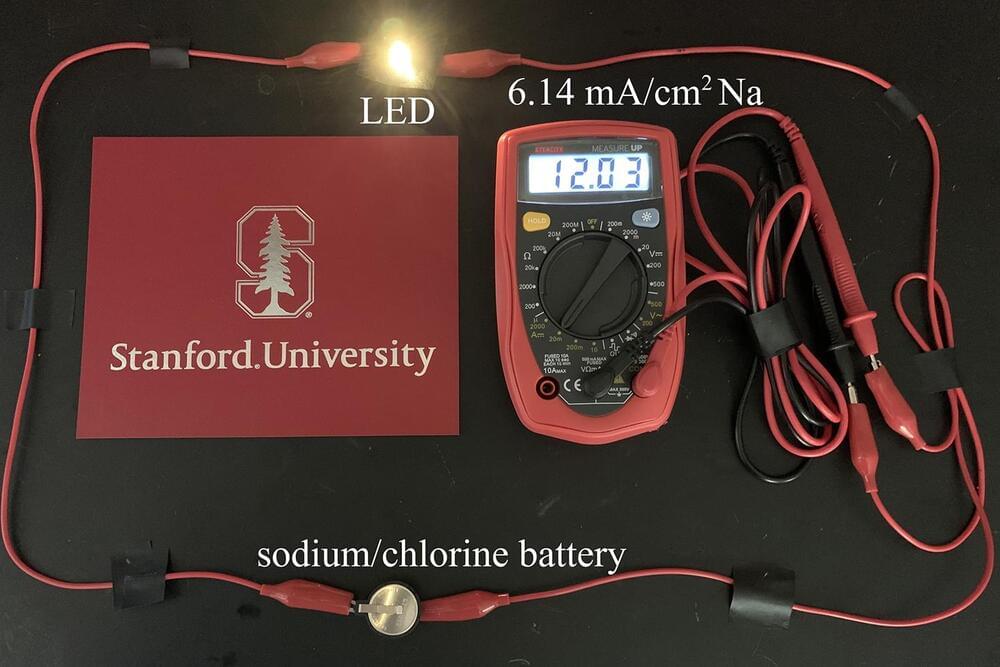

Researchers at North Carolina State University have created a soft and stretchable device that converts movement into electricity and can work in wet environments.

“Mechanical energy—such as the kinetic energy of wind, waves, body movement and vibrations from motors—is abundant,” says Michael Dickey, corresponding author of a paper on the work and Camille & Henry Dreyfus Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at NC State. “We have created a device that can turn this type of mechanical motion into electricity. And one of its remarkable attributes is that it works perfectly well underwater.”

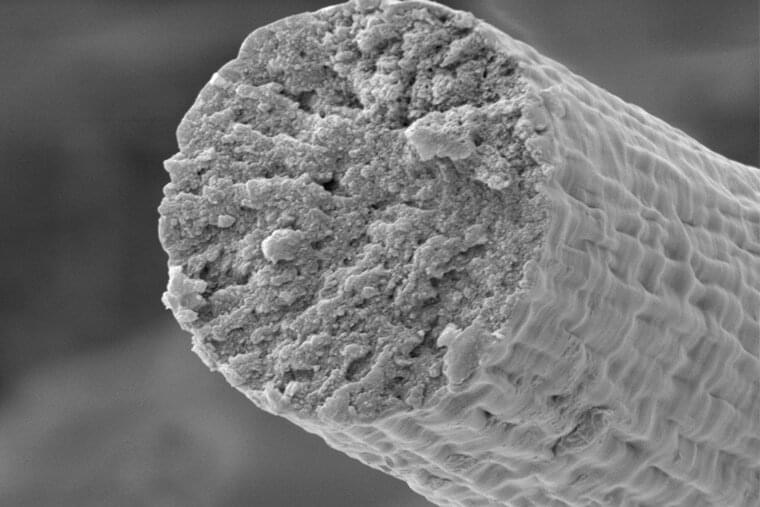

The heart of the energy harvester is a liquid metal alloy of gallium and indium. The alloy is encased in a hydrogel—a soft, elastic polymer swollen with water.