Category: biotech/medical

Brain ‘Noise’ Keeps Nerve Connections Young

The findings, published in Nature Communications, could have important implications for human health: minis have been found at every type of synapse studied so far, and defects in miniature neurotransmission have been linked to range of neurodevelopmental disorders in children. Figuring out how a reduction in miniature neurotransmission changes the structure of synapses, and how that in turn affects behavior, could help to better understand neurodegenerative disorders and other brain conditions.

Summary: Study reveals how miniature release events help to keep neurons intact and preserve motor neuron function in aging insects.

Source: EPFL

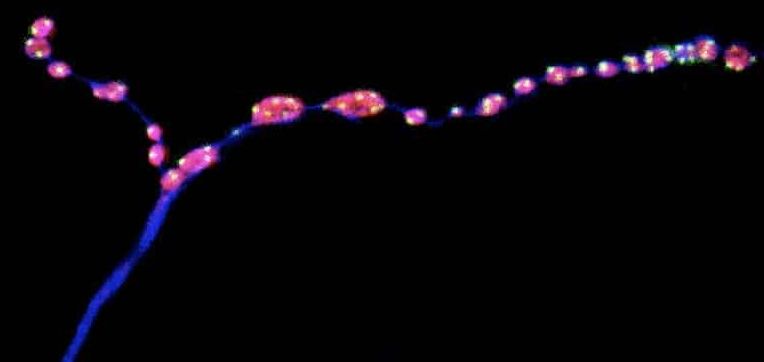

Neurons communicate through rapid electrical signals that regulate the release of neurotransmitters, the brain’s chemical messengers. Once transmitted across a neuron, electrical signals cause the juncture with another neuron, known as a synapse, to release droplets filled with neurotransmitters that pass the information on to the next neuron. This type of neuron-to-neuron communication is known as evoked neurotransmission.

However, some neurotransmitter-packed droplets are released at the synapse even in the absence of electrical impulses. These miniature release events — or minis — have long been regarded as ‘background noise’, says Brian McCabe, Director of the Laboratory of Neural Genetics and Disease and a Professor in the EPFL Brain Mind Institute.

Pathogenic fungi colonize microplastics in soils

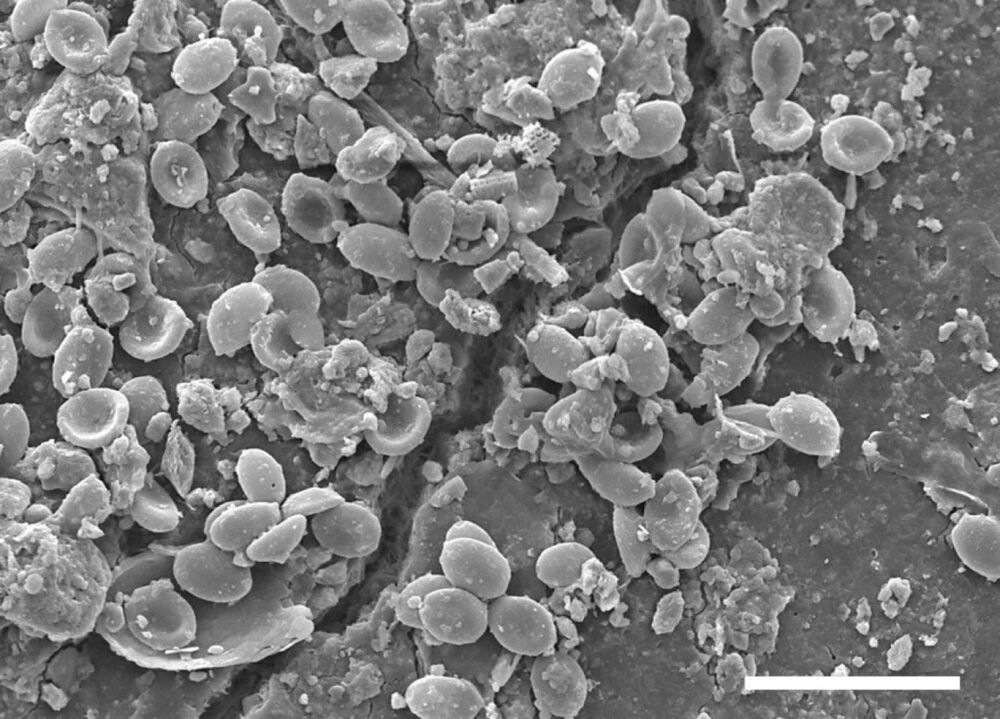

Representatives of numerous pathogenic fungal species are finding new habitat on microplastic particles in the soil and could thus be one of the possible causes of an increase in fungal infections. Researchers from Bayreuth, Hannover and Munich demonstrated this in a new study. Using high-throughput methods, the scientists analyzed fungal communities from soil samples taken from sites near human settlements in western Kenya. The findings of this research have been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

This study is the first to focus on fungal communities on microplastic particles in the soil. Many of the species detected belong to groups of fungi that are pathogenic to plants, animals and humans. Pathogenic microfungi are able to colonize the otherwise inhospitable surfaces of microplastic particles due to their characteristic adhesive lifestyle. Furthermore, they are able to withstand strong solar radiation and heat to which they are exposed on soil surfaces.

“We were able to observe all stages of fungal biofilm formation on the microplastic particles recovered from the soil samples. In doing so, we were able to demonstrate that fungi not only grow, but also reproduce in the so-called plastisphere. The data we obtained from microscopic examinations and DNA analyses supports the assumption that fungi systematically colonize microplastics in the soil. Moreover, they provide evidence that microplastics in soil accumulate certain pathogenic fungal species: some species dangerous to humans, including black fungi and cryptococcal yeast fungi, are present on the surfaces of microplastic particles in higher concentrations than in the surrounding soil. Our study therefore justifies the presumption that microplastics in soil are a potential source of fungal infections,” says Gerasimos Gkoutselis M.Sc., lead author of the study and doctoral student at the University of Bayreuth’s Department of Mycology.

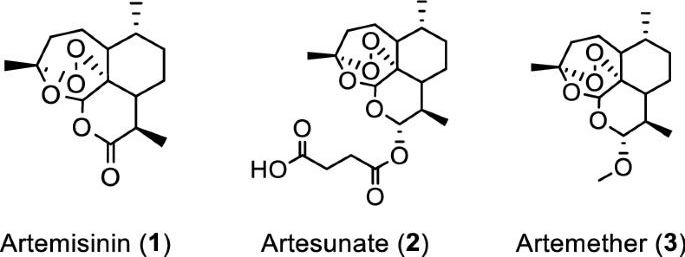

In vitro efficacy of artemisinin-based treatments against SARS-CoV-2

Artemisia annua plants grown from a cultivated seed line in Kentucky, USA, were extracted using either absolute ethanol or distilled water at 50 °C for 200 min and analyzed, as described in “Materials and methods” and Supplementary Information (Figures S1 and S2). Solids were removed by filtration and the solvents were evaporated. The extracted materials were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (ethanol extract) or a DMSO: water mixture (3:1 for aqueous extract) and filtered (see supporting information for details). Artemisinin (Fig. 1, (1)) was synthesized and purified following a published procedure or purchased17, while artesunate (Fig. 1, (2)) and artemether (Fig. 1, (3)) were only obtained from commercial sources.

Initial experiments were carried out at FU Berlin, Germany. To initially screen whether extracts and pure artemisinin were active against SARS-CoV-2, their antiviral activity was tested by pretreating VeroE6 cells at different time points during 120 min with selected concentrations of the extracts or compounds prior to infection with the first European SARS-CoV-2 isolated in München (SARS-CoV-2/human/Germany/BavPat 1/2020). The virus-drug mixture was then removed and cells were overlaid with medium containing 1.3% carboxymethylcellulose to prevent virus release into the medium. DMSO was used as a negative control. Plaque numbers were determined either by indirect immunofluorescence using a mixture of antibodies to SARS-CoV N protein18 or by staining with crystal violet19. The addition of either ethanolic or aqueous A. annua extracts prior to virus addition resulted in reduced plaque formation in a concentration dependent manner, while artemisinin exhibited little antiviral activity (Supplemental Tables S1 – S8).

Concentration–response experiments were carried out at Copenhagen University Hospital-Hvidovre. In these experiments the Danish SARS-CoV-2 isolate SARS-CoV-2/human/Denmark/DK-AHH1/2020 was used employing a 96-well plate based concentration–response antiviral treatment assay, allowing for multiple replicates per concentration, as described in “Materials and methods” and Supplementary Information (Figures S3 and S4)20,21. Seven replicates were measured at each concentration and a range of concentrations was evaluated to increase data accuracy when compared to the plaque-reduction assay, which was carried out in duplicates. Extracts or compounds were added to VeroE6 cells either 1.5 h prior to (pretreatment (pt)) or 1 h post infection (treatment (t)), respectively, followed by a 2-day incubation of virus with extracts or compounds. Both protocols yielded similar results, with slightly lower median effective concentration (EC50) values observed for treatment assays.

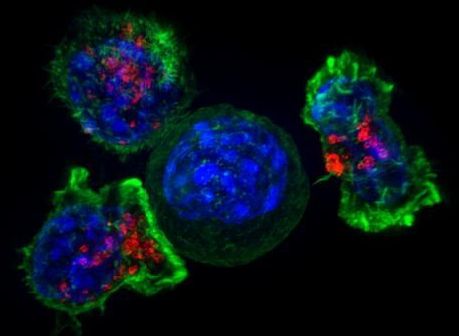

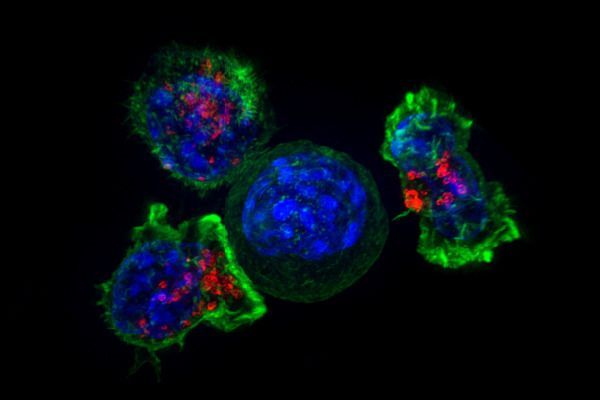

Transcription Factor Protects Tumor-Fighting CAR-T Cells from Burn-Out

Researchers at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) have demonstrated how cancer-fighting T cells can be engineered to clear tumors without succumbing to T cell exhaustion, a phenomenon that results in T cells giving up the antitumor fight after prolonged periods of overactivity. The newly reported findings demonstrated the key role of the transcription factor BATF in the cellular pathway that triggers T cell exhaustion, and showed how increasing levels of BATF in these cells boosts their cancer-fighting ability, with the help of another transcription factor IRF4. The results suggest a potential approach to increasing the effectiveness of CAR T cell-based immunotherapy against tumors, which is important because T cell exhaustion plagues even the most cutting-edge cancer immunotherapies.

“The idea is to give the cells a little bit of armor against the exhaustion program,” said LJI professor Patrick Hogan, PhD. “The cells can go into the tumor to do their job, and then they can stick around as memory cells.” The LJI team, headed by Hogan and LJI professor Anjana Rao, PhD, report on their studies in Nature Immunology, in a paper titled, “BATF and IRF4 cooperate to counter exhaustion in tumor-infiltrating CAR T cells.”

Fighting a tumor is a marathon, not a sprint. For cancer-fighting CD8+ T cells, the race is sometimes just too long, and they quite fighting. “CD8+ T cells that encounter antigen together with effective costimulatory signals mount strong effector responses that are able to clear pathogen-infected cells and tumor cells,” the team wrote. “In contrast, CD8+ T cells that infiltrate solid tumors and are exposed to prolonged antigen stimulation in the absence of adequate costimulation enter a hyporesponsive (exhausted or dysfunctional) state in which they do not effectively destroy tumor cells.”

Dr. Jean M. Hebert, Ph.D. — Replacing Aging — Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Replacing Aging — Dr. Jean M. Hebert, Ph.D. Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Dr. Jean M. Hebert, Ph.D. (https://einsteinmed.org/faculty/9069/jean-hebert/) is Professor in the Department of Genetics and in the Dominick P. Purpura Department of Neuroscience, at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

He’s also the author of the book Replacing Aging, which describes how regenerative medicine will beat aging.

With a Ph.D. in Genetics from the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Hebert’s current lab’s projects fall into two groups.

First, they focus on using the mouse neocortex as a platform for testing the ability of multi-cell type grafts (increasingly resembling normal neocortex) to integrate with host tissue.

Secondly, they are testing the ability of genetically engineered microglia that disperse throughout the adult neocortex to bolster neocortical function.

These highly collaborative projects require a range of multidisciplinary methods, including molecular genetics, human embryonic stem cell biology, transcriptomics, surgery, electrophysiology, live brain imaging, and behavioral tests, among others.

The virus trap

To date, there are no effective antidotes against most virus infections. An interdisciplinary research team at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) has now developed a new approach: they engulf and neutralize viruses with nano-capsules tailored from genetic material using the DNA origami method. The strategy has already been tested against hepatitis and adeno-associated viruses in cell cultures. It may also prove successful against corona viruses.

Why identical mutations cause different types of cancer

“Our studies in mice revealed how genes co-operate to cause cancer in different organs. We identified main players, the order in which they occur during tumor progression, and the molecular processes how they turn normal cells into threatening cancers. Such processes are potential targets for new treatments”.

Why do alterations of certain genes cause cancer only in specific organs of the human body? Scientists at the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), the Technical University of Munich (TUM), and the University Medical Center Göttingen have now demonstrated that cells originating from different organs are differentially susceptible to activating mutations in cancer drivers: The same mutation in precursor cells of the pancreas or the bile duct leads to fundamental different outcomes. The team discovered for the first time that tissue specific genetic interactions are responsible for the differential susceptibility of the biliary and the pancreatic epithelium towards transformation by oncogenes. The new findings could guide more precise therapeutic decision making in the future.

There have been no major improvements in the treatment of pancreatic and biliary tract cancer in the last decades and no effective targeted therapies are available to date. “The situation for patients with pancreatic and extrahepatic bile duct cancer is still very depressing with approximately only 10% of patients surviving five years,” says Dieter Saur, DKTK Professor for Translational Cancer Research at TUM’s university hospital Klinikum rechts der Isar, DKTK partner site Munich.

DKTK is a consortium centered around the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, which has long-term collaborative partnerships with specialist oncological centers at universities across Germany.

New universal coronavirus vaccine could prevent future pandemics

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Scientists at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health have developed a vaccine that could be effective against COVID-19, its variants — and a future coronavirus pandemic.

While no one knows which virus may cause the next outbreak, coronaviruses remain a threat after causing the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the global COVID-19 pandemic.

According to a study published June 22 in Science, the vaccine designed at UNC-Chapel Hill protected mice from the current SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, plus a group of coronaviruses known to make the jump from animals to humans.