A melding of biology and physics first suggested in the 1920s is enjoying a revival as evidence mounts. Stephen Fleischfresser reports.

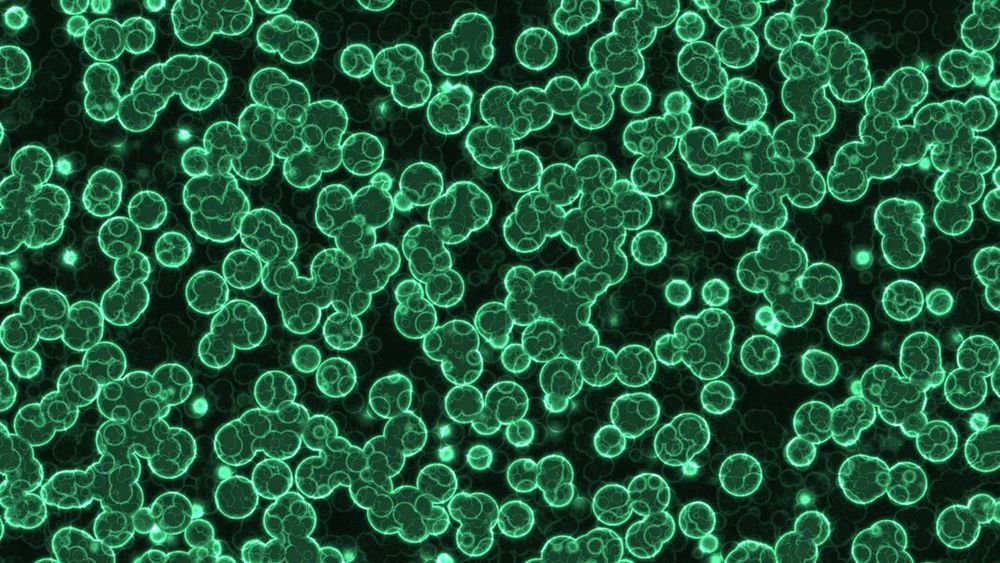

“We looked at a group of tiny, green bacteria called Prochlorococcus which is the most abundant photosynthetic organism on Earth, with a global population of around three octillion (~1027) individuals,” says Sasha.

Ten per cent of the oxygen we breathe comes from just one kind of bacteria in the ocean. Now laboratory tests have shown that these bacteria are susceptible to plastic pollution, according to a study published in Communications Biology.

“We found that exposure to chemicals leaching from plastic pollution interfered with the growth, photosynthesis and oxygen production of Prochlorococcus, the ocean’s most abundant photosynthetic bacteria,” says lead author and Macquarie University researcher Dr. Sasha Tetu.

“Now we’d like to explore if plastic pollution is having the same impact on these microbes in the ocean.”

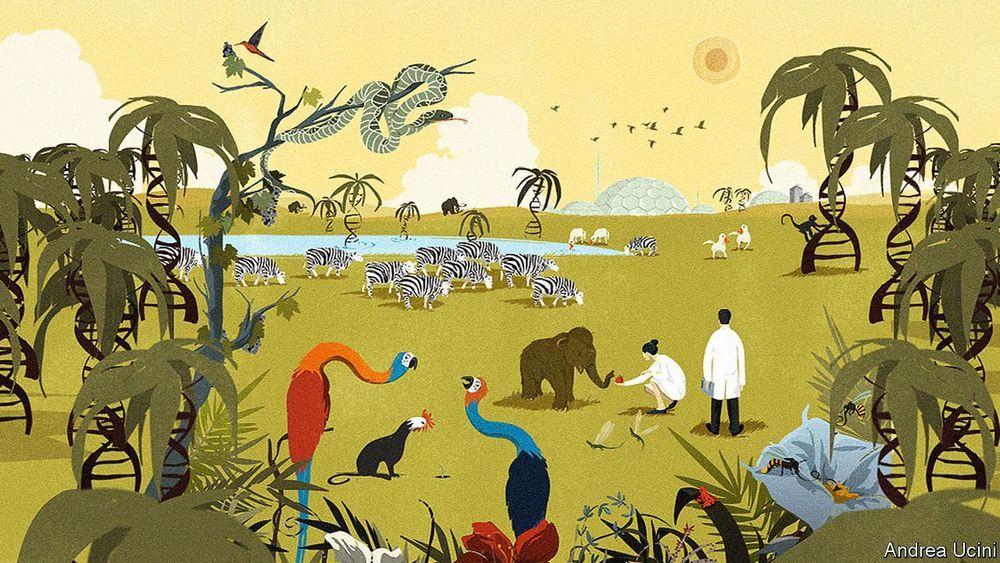

It’s very easy to forget that complex life on Earth almost missed the boat entirely. As the Sun’s luminosity gradually increases, the oceans will boil away, and the planet will no longer be in the habitable zone for life as we know it. Okay, we likely have a billion years before this happens—by which point our species will probably have destroyed itself or moved away from Earth—but Earth itself is 4.5 billion years old or so, and eukaryotic life only started to diversify 800 million or so years ago, at the end of the “boring billion.”

In other words, life seems to have arisen around four billion years ago, shortly after Earth formed, but then a few billion years passed before anything complex evolved. Another few hundred million years of bacteria, algae, and microbes sliding around in the anoxic sludge of the boring billion, and intelligent life might never have evolved at all.

Unraveling the geologic mysteries of the boring billion, and why it ended when it did, is a complex scientific question. Different parts of the earth system, including plate tectonics, the atmosphere, and the biosphere of simple lichens and cyanobacteria interacted to eventually produce the conditions for life to diversify, flourish, and grow more complex. But it is generally accepted that simple cyanobacteria (single-celled organisms that can produce oxygen through photosynthesis) were key players in providing Earth’s atmosphere and oceans with oxygen, which then allowed complex life to flourish.

New research published in Nature Scientific Reports (opens in new window) has found that a hormone produced by plants under stress can be applied to crops to alleviate the damage caused by salty soils. The team of researchers from Western Sydney University and the University of Queensland identified a naturally-occurring chemical in plants that reduces the symptoms of salt stress in plants when applied to soil, enabling the test plants to increase their growth by up to 32 times compared with untreated plants.

Salinity is a huge issue across the world, affecting more than 220 million hectares of the world’s irrigated farming and food-producing land. Salinity occurs when salty irrigation water is repeatedly applied to crops, leading to progressively increasing levels of salt in the soil which reduces crop yields, increases susceptibility to drought and damages soil microbiology. Scientists have long tried to find ways to breed salt-tolerance or develop methods that remove salt, and this new research is promising in its potential ability to reduce the damage in crop plants that results from salt.

“We identified a compound called ACC that occurs naturally in plants when they become stressed by drought, heat or salty conditions,” said Dr. Hongwei Liu, Postdoctoral Fellow in Soil Biology and Genomics at the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at Western Sydney University.

Bruce Damer is a living legend and international man of mystery – specifically, the mystery of our cosmos, to which he’s devoted his life to exploring: the origins of life, simulating artificial life in computers, deriving amazing new plans for asteroid mining, and cultivating his ability to receive scientific inspiration from “endotripping” (in which he stimulates his brain’s own release of psychoactive compounds known to increase functional connectivity between brain regions). He’s about to work with Google to adapt his origins of life research to simulated models of the increasingly exciting hot springs origin hypothesis he’s been working on with Dave Deamer of UC Santa Cruz for the last several years. And he’s been traveling around the world experimenting with thermal pools, getting extremely close to actually creating new living systems in situ as evidence of their model. Not to mention his talks with numerous national and private space agencies to take the S.H.E.P.H.E.R.D. asteroid mining scheme into space to kickstart the division and reproduction of our biosphere among/between the stars…

The world’s oceans soak up about a quarter of the carbon dioxide that humans pump into the air each year—a powerful brake on the greenhouse effect. In addition to purely physical and chemical processes, a large part of this is taken up by photosynthetic plankton as they incorporate carbon into their bodies. When plankton die, they sink, taking the carbon with them. Some part of this organic rain will end up locked into the deep ocean, insulated from the atmosphere for centuries or more. But what the ocean takes, the ocean also gives back. Before many of the remains get very far, they are consumed by aerobic bacteria. And, just like us, those bacteria respire by taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide. Much of that regenerated CO2 thus ends up back in the air.

A new study suggests that CO2 regeneration may become faster in many regions of the world as the oceans warm with changing climate. This, in turn, may reduce the deep oceans’ ability to keep carbon locked up. The study shows that in many cases, bacteria are consuming more plankton at shallower depths than previously believed, and that the conditions under which they do this will spread as water temperatures rise. The study was published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The results are telling us that warming will cause faster recycling of carbon in many areas, and that means less carbon will reach the deep ocean and get stored there,” said study coauthor Robert Anderson, an oceanographer at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.