Synthetic biology tools used to engineer T cells that work like living computers and recognize antigen combinations in solid tumors.

Plant scientists have revolutionised science and innovation. Research around the cell or cell biology was born out of plant science.

Researching plants is vital for our food security, maintaining our ecosystems and in our fight against climate change. Plant science is equally important to generate new knowledge that breaks disciplinary barriers to revolutionise several fields of research and innovation. But despite its valuable contribution, scientists and prospective young scientists often overlook plant science. It’s because of this low recognition, plant science doesn’t get the same prestige as other disciplines. This is detrimental to the future of plant science as bright young students continue to choose a career away from plant science. I never considered studying plants myself — it was entirely accidental that I studied plant science.

In other words, scientists and prize committees question the influence of basic plant science across different disciplines.

But the fact is that ever since the early days of science, plants have been central to breakthroughs. Discoveries in plant science have enabled technological advances that we enjoy today. Therefore, I’m aiming to write a series of blog posts to highlight a few significant findings from research in plants. Here, I explain how plant research revolutionised the field of cell biology.

Computational molecular physics (CMP) aims to leverage the laws of physics to understand not just static structures but also the motions and actions of biomolecules. Applying CMP to proteins has required either simplifying the physical models or running simulations that are shorter than the time scale of the biological activity. Brini et al. reviewed advances that are moving CMP to time scales that match biological events such as protein folding, ligand unbinding, and some conformational changes. They also highlight the role of blind competitions in driving the field forward. New methods such as deep learning approaches are likely to make CMP an increasingly powerful tool in describing proteins in action.

Science, this issue p.

### BACKGROUND

Subramanian Sundaram, a biological engineer affiliated with both Boston University and Harvard has been looking into the current state of robot hands and proposed ideas regarding where new research might be heading. He has published a Perspective piece in the journal Science outlining the current state of robotic hand engineering.

By almost any measure, robot hand design has evolved into sophisticated territory—robot hands can not only pick things up and let them go, they can sometimes “feel” things and respond in human-like ways—and in many cases, do it with extreme dexterity. Unfortunately, despite substantial inroads to giving robot hands human-like abilities, they still fall far short. Sundaram notes that one area where they need major improvement is in sensing things the way humans do, namely: feeling pressure, temperature and that hard-to-classify sense, pleasure. You cannot tickle a robot hand, for example, and expect a human-like response. Sundaram explains in great detail what is known about the human hand and how it processes sensations, and suggests that robot analogs might possible. He notes that not everything about a robot hand needs to be done in the same way as the human hand.

Some of the greatest medical discoveries of the 20th century came from physicists who switched careers and became biologists. Francis Crick, who won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology and helped identify the structure of DNA, started his career as a physicist, as did Leo Szilard who conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, writing the letter for Albert Einstein’s signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb, but spent the last decades of his life doing pioneering work in biology, including the first cloning of a human cell.

Today, a group of world-renowned researchers at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics with expertise from cosmology to quantum gravity are using physics to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

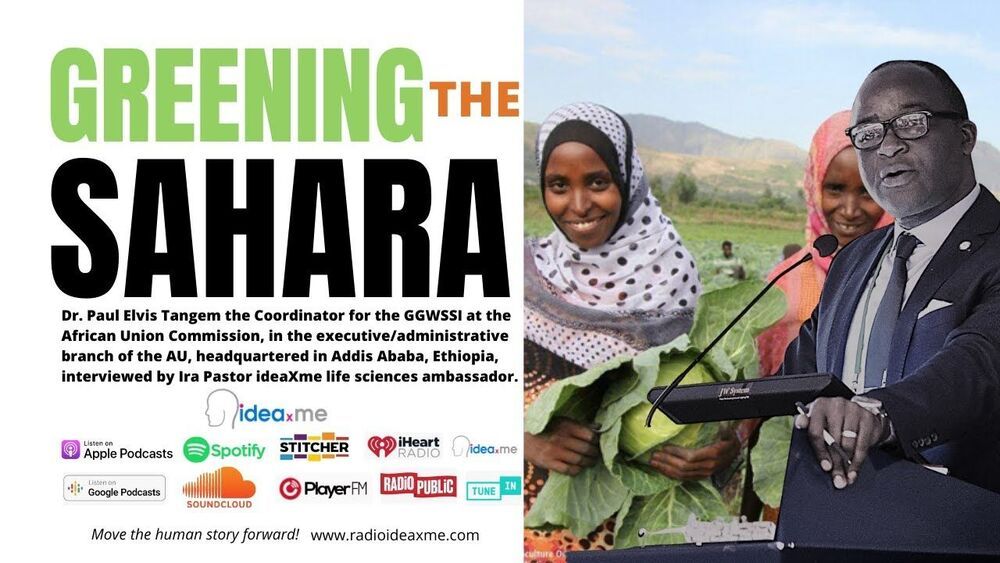

Greening the Desert / De-Desertification.

Ira Pastor, ideaXme life sciences ambassador interviews Dr. Paul Elvis Tangem the Coordinator for the GGWSSI at the African Union Commission, in the executive/administrative branch of the AU, headquartered in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Desertification is a type of land degradation in dry-lands in which biological productivity is lost due to natural processes, or induced by human activities, whereby fertile areas become increasingly arid, and may be caused by a variety of factors, such as climate change and over exploitation of soil.

One of the countermeasures for mitigating or reversing the effects of desertification is reforestation and in 2007 the African Union (AU) started the Great Green Wall Initiative (GGWSSI) Africa project in order to combat desertification in 20 countries across the Sahel and Sahara regions. The wall is projected to be 8,000 km wide, stretching across the entire width of the continent and has US$8 billion dollars in support so far. To date, the project has restored 36 million hectares of land, and by 2030, the initiative plans to restore a total of 100 million hectares. The Great Green Wall has created many job opportunities for the participating countries, with over 20,000 jobs created in Nigeria alone.

Dr. Paul Elvis Tangem is the Coordinator for the GGWSSI at the African Union Commission, in the executive/administrative branch of the AU, headquartered in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Before joining the African Union Commission, Dr. Tangem worked as Regional Enterprise Development Manager for Tree Aid International, a UK based international development charity. He also worked with The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (UN-FAO) as Technical adviser for the programs to promote different groups engaged in forest products based enterprises. He has also served with other organizations including Centre in Scotland, Environmental Justice Foundation, London, and the Watershed Task Group in Cameroon. He is also a mentor and coach, and is behind the establishment of well known start-ups in Cameroon, West Africa.

Dr. Tangem holds a BSc from University of Dschang — Cameroon, MSc in Ecology & Management University of Edinburgh, an Executive MBA from PGSM Paris, and PH.D in Business Administration, and several other certificates and diplomas. He is a member of several professional networks including Junior Chambers International where is a Senator, and a pioneer member of World Greening Alliance created by World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and Elion Group in China.

On this episode we will hear from Dr. Tangem about.

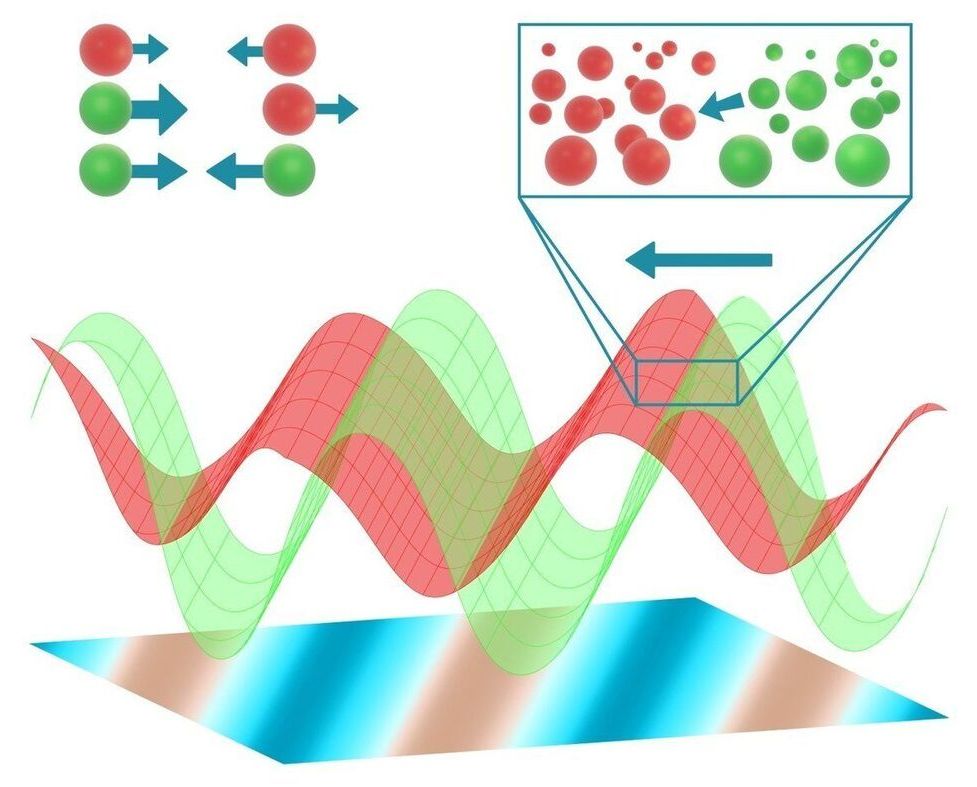

At first glance, a pack of wolves has little to do with a vinaigrette. However, a team led by Ramin Golestanian, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization, has developed a model that establishes a link between the movement of predators and prey and the segregation of vinegar and oil. They expanded a theoretical framework that until now was only valid for inanimate matter. In addition to predators and prey, other living systems such as enzymes or self-organizing cells can now be described.

Order is not always apparent at first glance. If you ran with a pack of wolves hunting deer, the movements would appear disordered. However, if the hunt is observed from a bird’s eye view and over a longer period of time, patterns become apparent in the movement of the animals. In physics, such behavior is considered orderly. But how does this order emerge? The Department of Living Matter Physics of Ramin Golestanian is dedicated to this question and investigates the physical rules that govern motion in living or active systems. Golestanian’s aim is to reveal universal characteristics of active, living matter. This includes not only larger organisms such as predators and prey but also bacteria, enzymes and motor proteins as well as artificial systems such as micro-robots. When we describe a group of such active systems over great distances and long periods of time, the specific details of the systems lose importance.

In Project Apollo, life support was based on carrying pretty much everything that astronauts needed from launch to splashdown. That meant all of the food, air, and fuel. Fuel in particular took up most of the mass that was launched. The enormous three-stage Saturn-V rocket was basically a gigantic container for fuel, and even the Apollo spacecraft that the Saturn carried into space was mostly fuel, because fuel was needed also to return from the Moon. If NASA’s new Orion spacecraft takes astronauts back to the Moon, they’ll also use massive amounts of fuel going back and forth; and the same is true if they journey to a near-Earth asteroid. However, once a lunar base is set up, astronauts will be able use microorganisms carried from Earth to process lunar rock into fuel, along with oxygen. The latter is needed not just for breathing, but also in rocket engines where it mixes with the fuel.

Currently, there are microorganisms available naturally that draw energy from rock and in the process release chemical products that can be used as fuel. However, as with agricultural plants like corn and soy, modifying such organisms can potentially make a biologically-based lunar rock processing much more efficient. Synthetic biology refers to engineering organisms to pump out specific products under specific conditions. For spaceflight applications, organisms can be engineered specifically to live on the Moon, or for that matter on an asteroid, or on Mars, and to synthesize the consumables that humans will need in those environments.

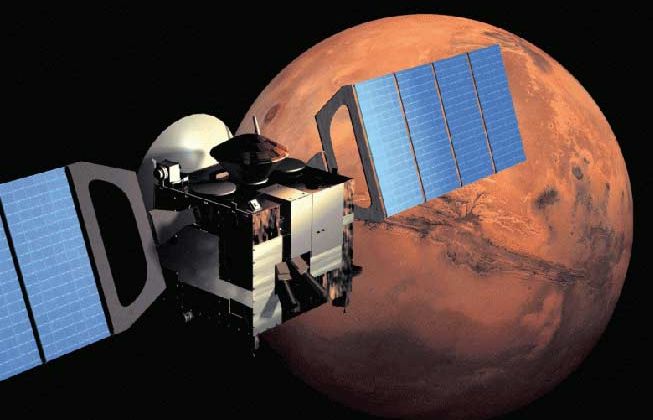

In the case of Mars, a major resource that can be processed by synthetic biology is the atmosphere. While the Martian air is extremely thin, it can be concentrated in a biological reactor. The principal component of the Martian air is carbon dioxide, which can be turned into oxygen, food, and rocket fuel by a variety of organisms that are native to Earth. As with the Moon rocks, however, genetic techniques can make targeted changes to organisms’ capabilities to allow them to do more than simply survive on Mars. They could be made to thrive there.

DARPA’s SIGMA+ program conducted a week-long deployment of advanced chemical and biological sensing systems in the Indianapolis metro region in August, collecting more than 250 hours of daily life background atmospheric data across five neighborhoods that helped train algorithms to more accurately detect chemical and biological threats. The testing marked the first time in the program the advanced laboratory grade instruments for chemical and biological sensing were successfully deployed as mobile sensors, increasing their versatility on the SIGMA+ network.

“Spending a week gathering real-world background data from a major Midwestern metropolitan region was extremely valuable as we further develop our SIGMA+ sensors and networks to provide city and regional-scale coverage for chem and bio threat detection,” said Mark Wrobel, program manager in DARPA’s Defense Sciences Office. “Collecting chemical and biological environment data provided an enhanced understanding of the urban environment and is helping us make refinements of the threat-detection algorithms to minimize false positives and false negatives.”

SIGMA+ expands on the original SIGMA program’s advanced capability to detect illicit radioactive and nuclear materials by developing new sensors and networks that would alert authorities with high sensitivity to chemical, biological, and explosives threats as well. SIGMA, which began in 2014, has demonstrated city-scale capability for detecting radiological threats and is now operationally deployed with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, helping protect the greater New York City region.