A team of scientists from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) inGermany, Givskud Zoo–Zootopia in Denmark and the University of Milan in Italy succeeded in producing the very first African lionin-vitroembryos after the vitrification of immature oocytes. For this specific method of cryopreservation, oocytes are collected directly after an animal is castrated or deceased and immediately frozen at-196°C in liquid nitrogen. This technique allows the storage of oocytes of valuable animals for an unlimited time, so that they can be used to produce offspring with the help of assisted reproduction techniques. The aim is to further improve and apply these methods to save highly endangered species such as the Asiatic lion from extinction. The current research on African lions as a model species is an important step in this direction. The results are reported in the scientific journal Cryobiology.

Lion oocytes are presumed to be very sensitive to chilling due to their high lipid content, resulting in poor revival following slow cooling. Vitrification can circumvent this problem, as the cells are frozen at ultra-fast speeds in solutions with a very high concentration of cryoprotective agents. This method prevents the formation of ice crystals in the cells, which could destroy them, and enables them to remain intact for an unlimited time to allow their use later on.

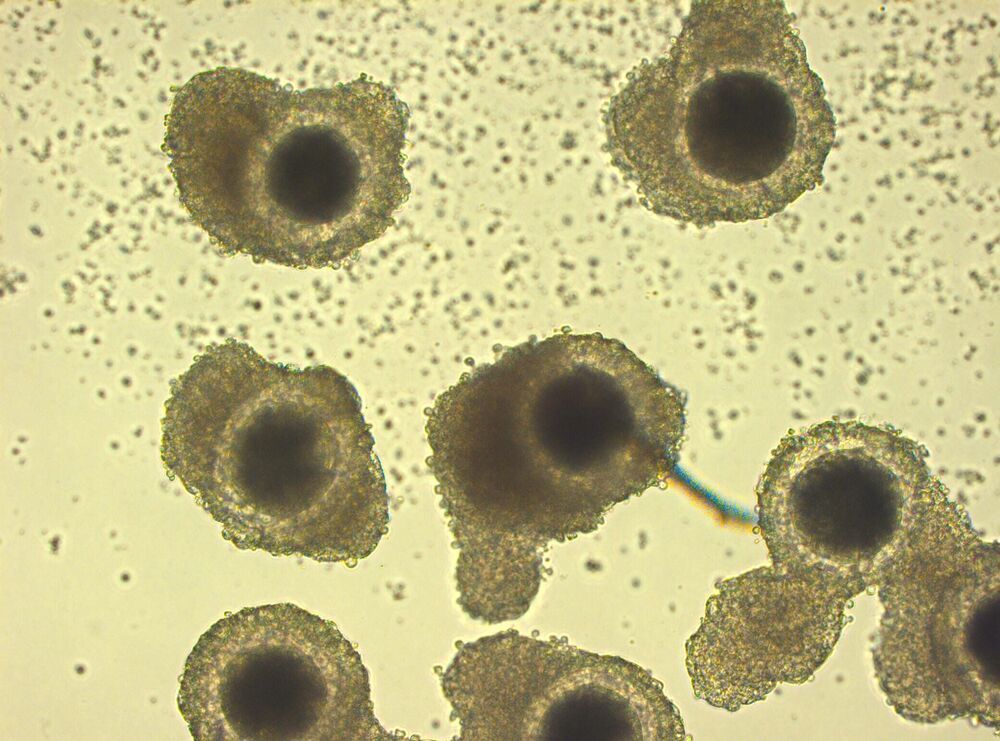

For the present research, the scientists collected oocytes from four African lionesses from Givskud Zoo—Zootopia after the animals had been euthanised for the purpose of population management. Half of the oocytes (60) were vitrified instantly. After six days of storage in liquid nitrogen, the vitrified oocytes were thawed and subjected toin-vitromaturation in an incubator at 39°C for a total of 32–34 hours. The other half (59) were used as control group and directly subjected toin-vitromaturation without a step of vitrification. Mature oocytes of both groups were then fertilized with frozen-thawed sperm from African lion males. “We could demonstrate a high proportion of surviving and matured oocytes in the group of vitrified oocytes. Almost 50% of them had matured, a proportion similar to that in the control group,” says Jennifer Zahmel, scientist at the Department of Reproduction Biology at the Leibniz-IZW.