Over 4000 patients in the United States alone are waiting for a heart transplant, while millions of others worldwide need hearts but are ineligible for the waitlist. The need for replacement organs is immense, and new approaches are needed to engineer artificial organs that are capable of repairing, supplementing, or replacing long-term organ function.

A team of researchers from Carnegie Mellon University has published a paper in Science that details a new technique allowing anyone to 3D bioprint tissue scaffolds out of collagen, the major structural protein in the human body. This first-of-its-kind method brings the field of tissue engineering one step closer to being able to 3D print a full-sized, adult human heart.

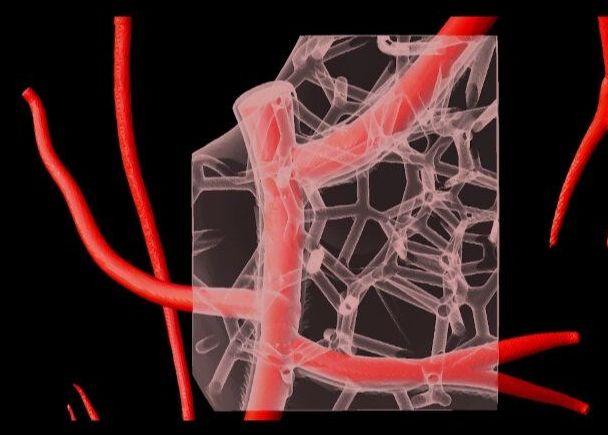

The technique, known as Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels (FRESH), has allowed the researchers to overcome many challenges associated with existing 3D bioprinting methods, and to achieve unprecedented resolution and fidelity using soft and living materials.

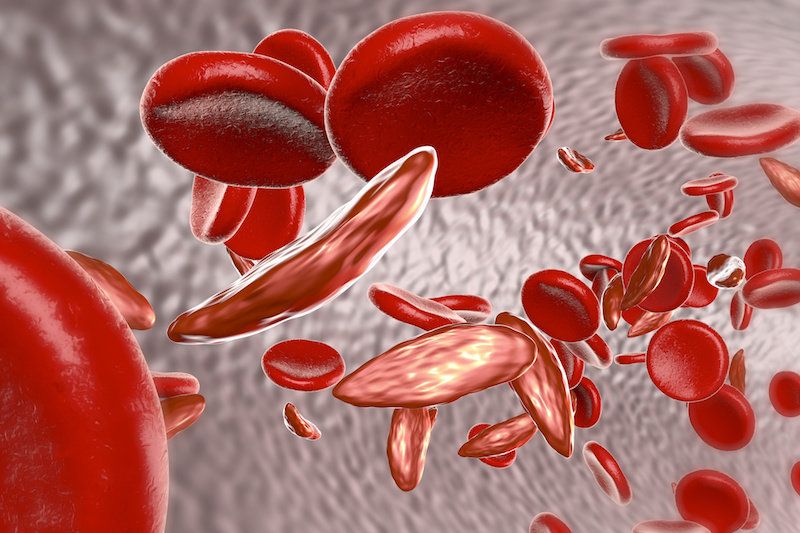

Each of the organs in the human body, such as the heart, is built from specialized cells that are held together by a biological scaffold called the extracellular matrix (ECM). This network of ECM proteins provides the structure and biochemical signals that cells need to carry out their normal function. However, until now it has not been possible to rebuild this complex ECM architecture using traditional biofabrication methods.