DNA hacking could save humanity—or destroy it. Author Jamie Metzl joins Inside the Hive to discuss the future of designer babies.

As the coming genetic revolution plays out, we’ll still have sex for most of the same reasons we do today. But we’ll increasingly not do it to procreate.

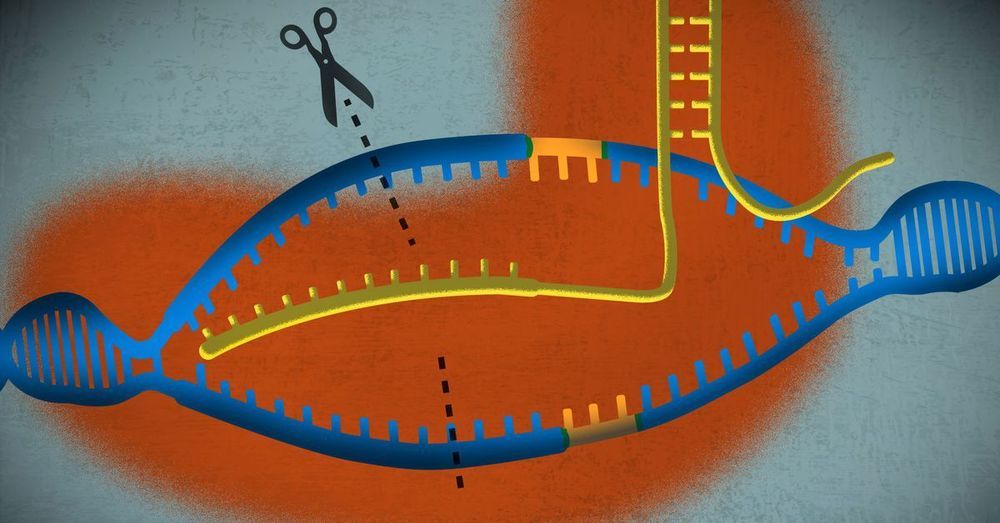

Another rocket booster will be the application of gene editing technologies like CRISPR to edit the genomes of pre-implanted embryos or of the sperm and eggs used to create them. Just this week, Chinese researchers announced they had used CRISPR to edit the CCR5 gene in the pre-implanted embryos of a pair of Chinese twins to make them immune to HIV, the first ever case of gene editing humans and a harbinger of our genetically engineered future. The astounding complexity of the human genome will put limits on our ability to safely make too many simultaneous genetic changes to human embryos, but our ability and willingness to make these types of alterations to our future children will grow over time along with our knowledge and technological ability.

With so much at stake, prospective parents will increasingly have a stark choice when determining how to conceive their children. If they go the traditional route of sex, they will experience both the benign wisdom and unfathomable cruelty of nature. If they use IVF and increasingly informed embryo selection, they will eliminate most single gene mutation diseases and likely increase their children’s chances of living a longer and healthier life with more opportunity than their unenhanced peers. But the optimizing parents could also set up their children for misery if these children don’t particularly enjoy what they have been optimized to become or see themselves as some type of freakish consumer product with emotions.

But although there will be pros and cons on each side, the fight between conception through good old-fashioned sex and conception in the lab will ultimately not be fair. Differences and competition within and between societies will pressure parents and societies to adopt ever more aggressive forms of reproductive technology if they believe doing so will open possibilities and create opportunities for the next generations rather than close them.

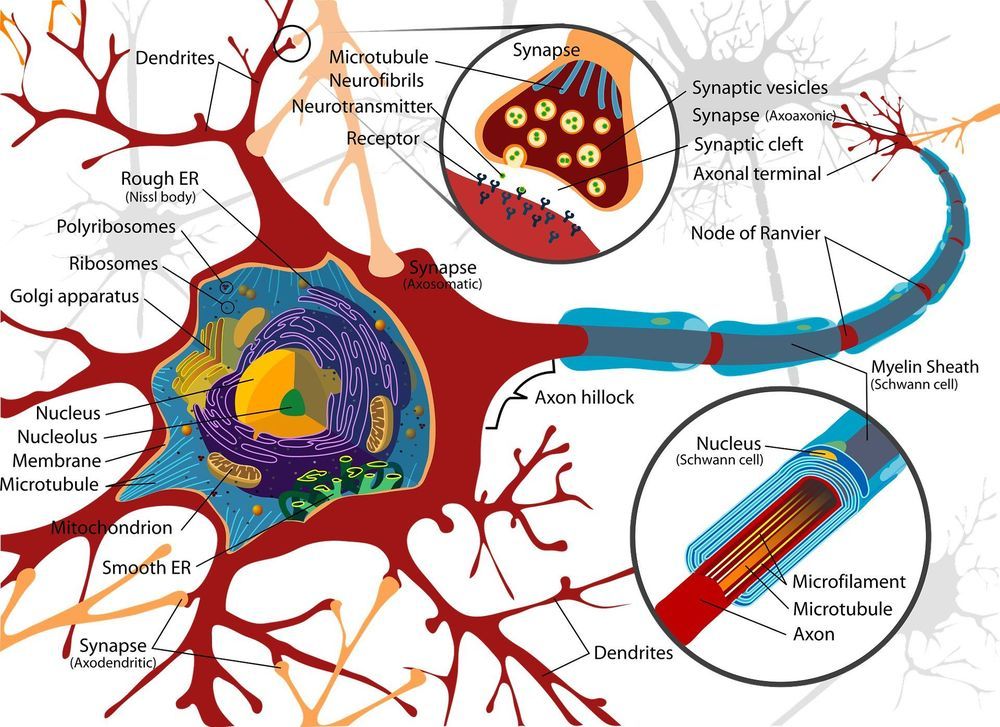

Synthetic biology researchers at Northwestern University have developed a system that can rapidly create cell-free ribosomes in a test tube, then select the ribosome that can perform a certain function.

The system, called ribosome synthesis and evolution (RISE), is an important step toward using ribosomes beyond their natural capabilities. The key feature of RISE is the ability to evolve ribosomes without cell viability constraints. The result could be new ways to synthesize materials, like nylon, or therapies, like new antibiotics that could address rising antibiotic resistance.

“Ribosomes have an extraordinary capability as the protein synthesis machinery of the cell,” said Michael Jewett, Walter P. Murphy Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering and director of the Center for Synthetic Biology at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering, who led the research. “But to synthesize proteins beyond those found in nature, we have to design and modify the ribosome to work with non-natural substrates. Developing ribosomes in vitro is an important part of that system, and we are very excited to have this new capability.”

Under the watchful eye of a microscope, busy little blobs scoot around in a field of liquid—moving forward, turning around, sometimes spinning in circles. Drop cellular debris onto the plain and the blobs will herd them into piles. Flick any blob onto its back and it’ll lie there like a flipped-over turtle.

Their behavior is reminiscent of a microscopic flatworm in pursuit of its prey, or even a tiny animal called a water bear—a creature complex enough in its bodily makeup to manage sophisticated behaviors. The resemblance is an illusion: These blobs consist of only two things, skin cells and heart cells from frogs.

Writing today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers describe how they’ve engineered so-calleds (from the species of frog, Xenopus laevis, whence their cells came) with the help of evolutionary algorithms. They hope that this new kind of organism—contracting cells and passive cells stuck together—and its eerily advanced behavior can help scientists unlock the mysteries of cellular communication.

There are decisions being made right now that could have an effect on global populations for generations to come. As part of this project, we commissioned an artist to investigate some of the themes raised in the podcasts. This work of fiction imagines a future where gene editing has become mainstream and discusses the moral, ethical and political divides that this might create.

Nearly every day, new discoveries are pushing the genetics revolution ever-forward. It’s hard to imagine it’s been only a century and a half since Gregor Mendl experimented with his peas, six decades since Watson and Crick identified the double helix, fourteen years since the completion of the human genome project, and five years since scientists began using CRISPR-cas9 for precision gene editing. Today, these tools are being used in ways that will transform agriculture, animal breeding, healthcare, and ultimately human evolution.

Common practices like in vitro fertilization (IVF) and preimplantation embryo selection make human genetic enhancement possible today. But as we learn more and more about what the genome does, we will be able to make increasingly more informed decisions about which embryos to implant in IVF in the near term and how to manipulate pre-implanted embryos in the longer-term. In our world of exponential scientific advancement, the genetic future will arrive far faster than most people currently understand or are prepared for.

Human genetic science is one of the most important and potentially beneficial advancements of our time, but the monumental health and well-being benefits of these technologies could be overwhelmed by fear, hysteria, and international conflict if a foundation for informed and inclusive public and governmental dialogue is not laid as soon as possible.

Great news.

The successful delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 modified immune cells to cancer patients represents the first U.S. clinical trial to test the gene editing approach in humans.

Researchers from the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania have published data suggesting that immune cells modified using the gene editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 are able to survive and function for months following delivery to cancer patients [1].

The research team demonstrated that T cells taken from patients and modified ex vivo (outside the body) can be safely returned to the patient and continue to survive and fight cancer. The cells were successfully edited in three ways: by deleting the TRAC, TRBC, and PDCD1 genes. In addition to these edits, a cancer-specific T cell receptor was inserted to target the NY-ESO-1 antigen to help improve the T cells’ ability to detect tumors.

The very nature of the human race is about to change. This change will be radical and rapid beyond anything in our species’ history. A chapter of our story just ended and the next chapter has begun.

This revolution in what it means to be human will be enabled by a new genetic technology that goes by the innocuous sounding name CRISPR, pronounced “crisper”. Many readers will already have seen this term in the news, and can expect much more of it in the mainstream media soon. CRISPR is an acronym for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and is to genomics what vi (Unix’s visual text editor) is to software. It is an editing technology which gives unprecedented power to genetic engineers: it turns them into genetic hackers. Before CRISPR, genetic engineering was slow, expensive, and inaccurate. With CRISPR, genome editing is cheap, accurate, and repeatable.

This essay is a very non-technical version of the CRISPR story concluding with a discussion of Gene Drive[1], a biological technique which, when used with CRISPR, gives even greater power to genetic engineers. The technical details go very deep and for those who are interested in diving in, I’ve included a number of useful pointers. At the end, I will very briefly discuss the implications of these two new technologies.

Ogba Educational Clinic

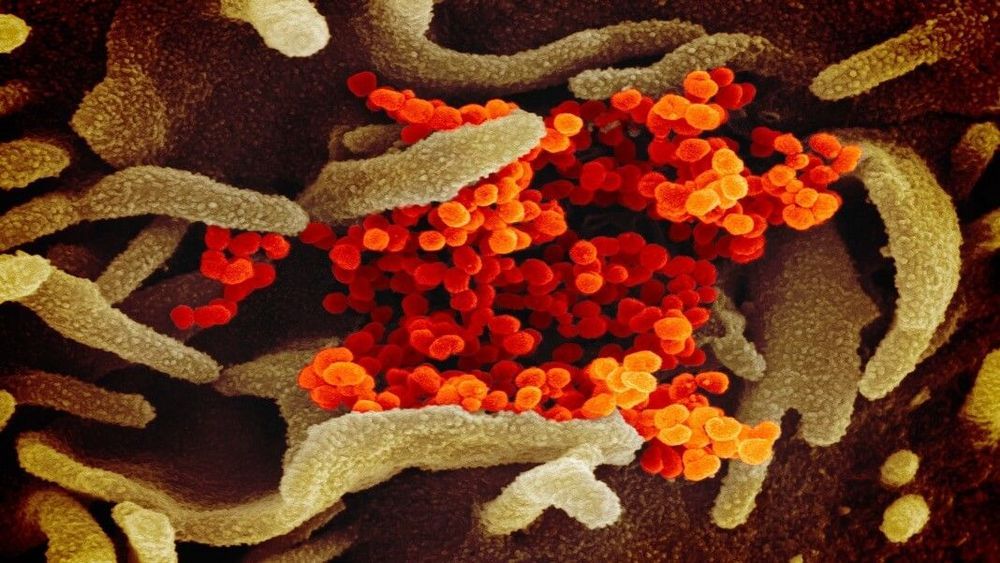

A nightmarish scene was burnt into my memory nearly two decades ago: Changainjie, Beijing’s normally chaotic “fifth avenue,” desolate without a sign of life. Schools shut, subways empty, people terrified to leave their homes. Every night the state TV channels reported new cases and new deaths. All the while, we had to face a chilling truth: the coronavirus, SARS, was so novel that no one understood how it spread or how to effectively treat it. No vaccines were in sight. In the end, it killed nearly 1,000 people.

It’s impossible not to draw parallels between SARS and the new coronavirus outbreak, COVID-19, that’s been ravaging China and spreading globally. Yet the response to the two epidemics also starkly highlights how far biotech and global collaborations have evolved in the past two decades. Advances in genetic sequencing technologies, synthetic biology, and open science are reshaping how we deal with potential global pandemics. In a way, the two epidemics hold up a mirror to science itself, reflecting both technological progress and a shift in ethos towards collaboration.

Let me be clear: any response to a new infectious disease is a murky mix of science, politics, racism, misinformation, and national egos. It’s naïve to point to better viral control and say it’s because of technology alone. Nevertheless, a comparison of the two outbreaks dramatically highlights how the scientific world has changed, for the better, in the last two decades.