Circa 2016 o.o

The federal government just proposed new rules that would allow researchers to grow human-animal hybrids for research, so long as they can’t think, feel, or breed.

The news did not sit well with Chinese scientists, who are still recovering from the CRISPR baby scandal. “It makes you wonder, if their reason for choosing to do this in a Chinese laboratory is because of our high-tech experimental setups, or because of loopholes in our laws?” lamented one anonymous commentator on China’s popular social media app, WeChat.

Their frustration is understandable. Earlier in April, a team from southern China came under international fire for sticking extra copies of human “intelligence-related” genes into macaque monkeys. And despite efforts to revamp its reputation in biomedical research ethics, China does have slacker rules in primate research compared to Western countries.

If you’re feeling icked out, you’re not alone. The morality and ethics of growing human-animal hybrids are far from clear. But creepiness aside, scientists do have two reasons for wading into these uncomfortable waters.

In a new publication in Nature Plants, assistant professor of Plant Science at the University of Maryland Yiping Qi has established a new CRISPR genome engineering system as viable in plants for the first time: CRISPR-Cas12b. CRISPR is often thought of as molecular scissors used for precision breeding to cut DNA so that a certain trait can be removed, replaced, or edited. Most people who know CRISPR are likely thinking of CRISPR-Cas9, the system that started it all. But Qi and his lab are constantly exploring new CRISPR tools that are more effective, efficient, and sophisticated for a variety of applications in crops that can help curb diseases, pests, and the effects of a changing climate. With CRISPR-Cas12b, Qi is presenting a system in plants that is versatile, customizable, and ultimately provides effective gene editing, activation, and repression all in one system.

“This is the first demonstration of this new CRISPR-Cas12b system for plant genome engineering, and we are excited to be able to fill in gaps and improve systems like this through new technology,” says Qi. “We wanted to develop a full package of tools for this system to show how useful it can be, so we focused not only on editing, but on developing gene repression and activation methods.”

It is this complete suite of methods that has ultimately been missing in other CRISPR systems in plants. The two major systems available before this paper in plants were CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR-Cas12a. CRISPR-Cas9 is popular for its simplicity and for recognizing very short DNA sequences to make its cuts in the genome, whereas CRISPR-Cas12a recognizes a different DNA targeting sequence and allows for larger staggered cuts in the DNA with additional complexity to customize the system. CRISPR-Cas12b is more similar to CRISPR-Cas12a as the names suggest, but there was never a strong ability to provide gene activation in plants with this system. CRISPR-Cas12b provides greater efficiency for gene activation and the potential for broader targeting sites for gene repression, making it useful in cases where genetic expression of a trait needs to be turned on/up (activation) or off/down (repression).

Essentially the microchip that heals article turns the normal process of healing into an accelerated way but eventually crispr could be used to make super fast healing and regeneration.

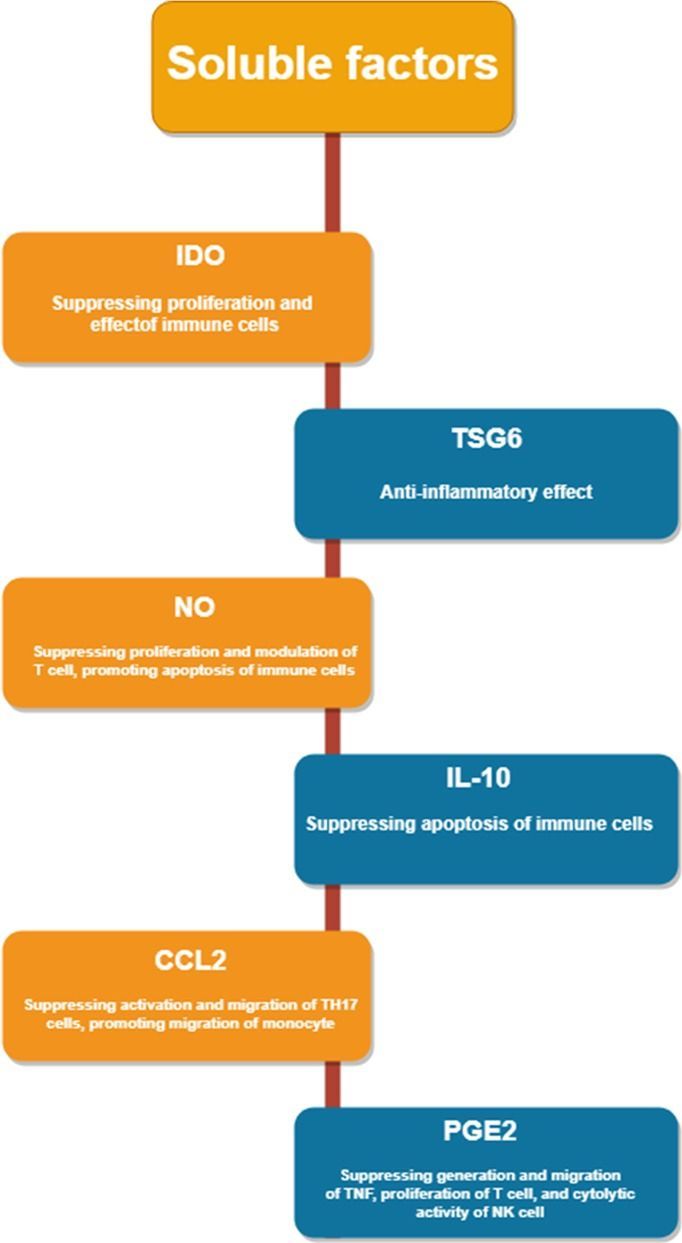

Normal wound healing is a dynamic and complex multiple phase process involving coordinated interactions between growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and various cells. Any failure in these phases may lead wounds to become chronic and have abnormal scar formation. Chronic wounds affect patients’ quality of life, since they require repetitive treatments and incur considerable medical costs. Thus, much effort has been focused on developing novel therapeutic approaches for wound treatment. Stem-cell-based therapeutic strategies have been proposed to treat these wounds. They have shown considerable potential for improving the rate and quality of wound healing and regenerating the skin. However, there are many challenges for using stem cells in skin regeneration. In this review, we present some sets of the data published on using embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, and adult stem cells in healing wounds. Additionally, we will discuss the different angles whereby these cells can contribute to their unique features and show the current drawbacks.

It’s 5pm in the Farrant household and Jack, six, and Thomas, four, are currently manifesting their desires in the form of Lego. To an outsider this looks like two small children playing with toys, but their mother Catherine proudly points out that Jack has built a yacht – something he is helping his family to acquire via visualisation exercises.

‘Dinner’s ready,’ calls out the nanny. In line with the family’s Paleo diet – of anti-inflammatory, natural foods – they have octopus cooked with lemongrass, and fish-bone broth. ‘Yes, my favourite,’ cries Jack happily, while his mum explains exactly what the broth is: ‘It’s an age-old elixir that’s made from boiling wild bones. It’s very high in iodine, which most of us are deficient in.’

After dinner, the children can continue to express their creativity, or watch some television – though if they’re going to do the latter after 6pm they need to put on their ‘blue-light blockers’, glasses with amber lenses to block the blue light of technology from affecting their sleep. ‘We also do red-light therapy,’ explains Catherine, pointing to a red dinosaur lamp in the boys’ bedroom. ‘It’s to help the body’s natural rhythms of sunset with exposure to red colours at night, and blue and white light in the morning.’

My editorial from today’s (3/18/19) Financial Times:

Far sooner than most people realise, the genetics revolution will transform the world within and around us. Although we think about genetic technologies primarily in the context of healthcare, these tools are set to change the way we make babies, the nature of the babies we make and, ultimately, our evolutionary trajectory as a species — and we are not remotely ready for what’s coming. Yet we must be, to optimise the benefits and minimise the potential harms of genetic technologies.

Scientists are now able to manipulate biology to a previously unimaginable degree. In the past year, we’ve seen two female mice having their own babies, dramatic increases in the precision of gene-editing tools, and the birth in China of the first gene-edited humans. As this science advances exponentially, however, the regulations guiding how it should best be used are struggling to keep up. If the applications race forward without appropriate guard rails, the danger increases that more scientists like He Jiankui, the Chinese biophysicist who genetically altered two girls, will put people’s health at risk. But if the regulations are hastily written before the issues are clear, are too strong or are not flexible enough, many people who would otherwise have benefited from applied genetic technologies will be condemned to unnecessary suffering or even death.

Scientists say they have used the gene editing tool CRISPR inside someone’s body for the first time — offering a new frontier for efforts to operate on DNA, the chemical code of life, to treat diseases.

A patient recently had it done at the Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland for an inherited form of blindness, according to the companies that make the treatment. The company would not give details on the patient or when the surgery occurred.

It may take up to a month to see if it worked to restore the patient’s vision. If the first few attempts seem safe, doctors plan to test it on 18 children and adults.

Scientists say they have used the gene editing tool CRISPR inside someone’s body for the first time, a new frontier for efforts to operate on DNA, the chemical code of life, to treat diseases.

A patient recently had it done at the Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland for an inherited form of blindness, the companies that make the treatment announced Wednesday. They would not give details on the patient or when the surgery occurred.

It may take up to a month to see if it worked to restore vision. If the first few attempts seem safe, doctors plan to test it on 18 children and adults.

If there was a public vote about human gene enhancement, would you vote YES or NO?

Our species is on the cusp of a revolution that will change every aspect of our lives but we’re hardly talking about it.

After three and a half billion years of evolution, two hundred and fifty thousand years of them as the ass-kicking bipedal hominins we call homo sapiens, we are on the verge of taking control of our evolutionary process unlike never before. This revolution will take hundreds of years to play out but it has already begun.

Sure, we influenced natural selection when we invented farming and modern medicine, but take a human baby from eleven thousand years ago and place him in a modern family and he’ll grow up just like any other kid. Then take a kid from a thousand years from now and place him in the same family. My belief is that the future child brought back to the present will not fit in nearly as well. He will be stronger and smarter with enhanced sensory and other capabilities. And we will have engineered him. We will have engineered us all.