Researchers have found half a dozen high-risk vulnerabilities in the latest firmware version for the Netgear Nighthawk R6700v3 router. At publishing time the flaws remain unpatched.

If you ask a physicist like me to explain how the world works, my lazy answer might be: “It follows the Standard Model.”

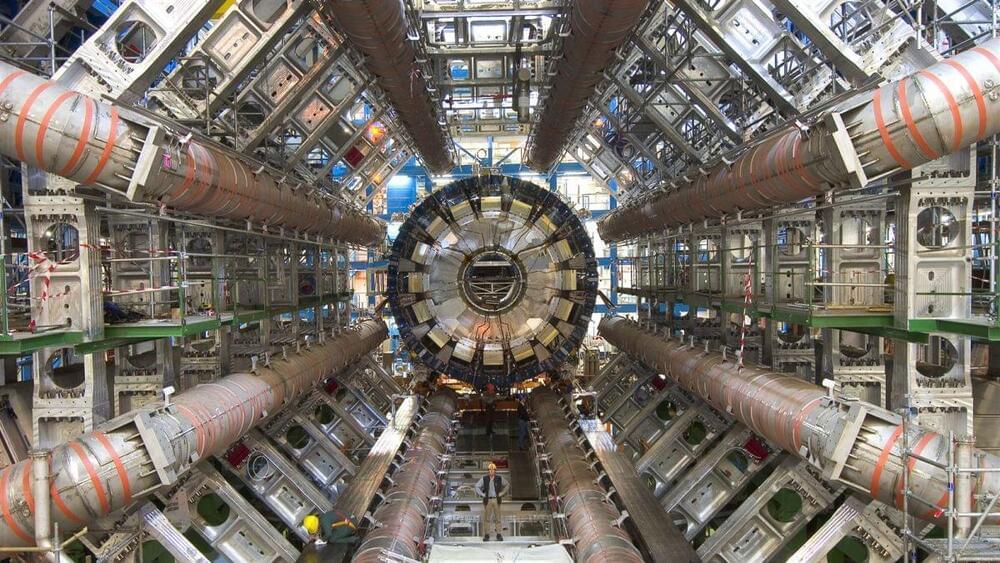

The Standard Model explains the fundamental physics of how the universe works. It has endured over 50 trips around the sun despite experimental physicists constantly probing for cracks in the model’s foundations.

With few exceptions, it has stood up to this scrutiny, passing experimental test after experimental test with flying colors. But this wildly successful model has conceptual gaps that suggest there is a bit more to be learned about how the universe works.

This year, billionaire CEO Elon Musk reached several milestones across Tesla, SpaceX and Starlink. WSJ reporters Rebecca Elliott and Micah Maidenberg break down some of his biggest moments in 2021 and what’s to come in 2022. Illustration: Tom Grillo.

In-Depth Features.

A global look at the economic and cultural forces shaping our world.

An on-chip superconducting isolator that does not rely on magnetic materials to break reciprocity is implemented, providing 45 dB of isolation at the qubit readout frequency.

High energy density (HED) laboratory plasmas are perhaps the most extreme states of matter ever produced on Earth. Normal plasmas are one of the four basic states of matter, along with solid, gases, and liquids. But HED plasmas have properties not found in normal plasmas under ordinary conditions. For example, matter in this state may simultaneously behave as a solid and a gas. In this state, materials that normally act as insulators for electrical charges instead become conductive metals. To create and study HED plasmas, scientists compress materials in solid or liquid form or bombard them with high energy particles or photons.

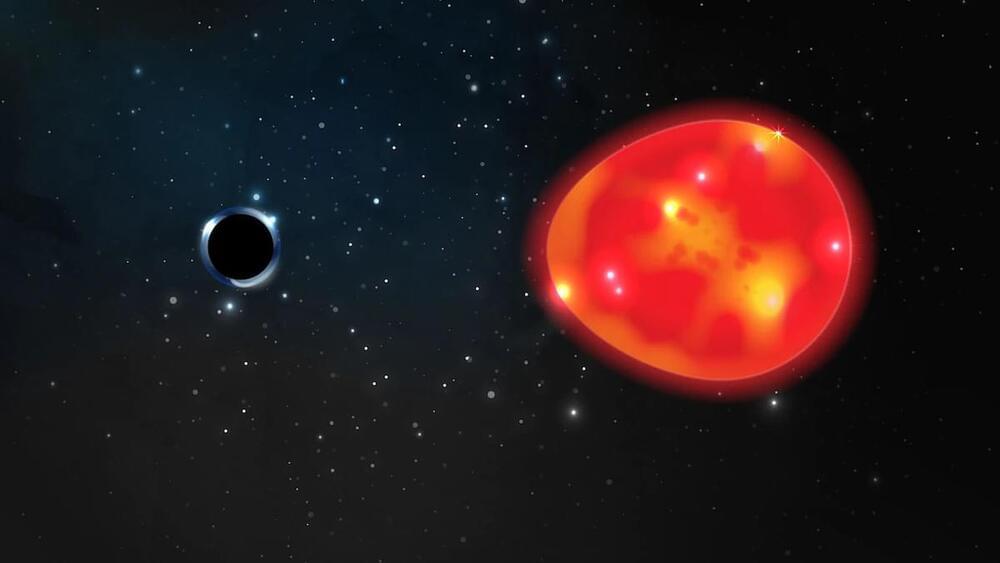

Dubbed the “unicorn,” the odd object is also among the smallest black holes ever found, and it may help solve an enduring mystery in astrophysics.

It’s hard to overemphasize how far computers have come and how they have transformed just about every aspect of our lives. From rudimentary devices like toasters to cutting-edge devices like spacecrafts, you’ll be hard pressed not to find these devices making use of some form of computing capability.

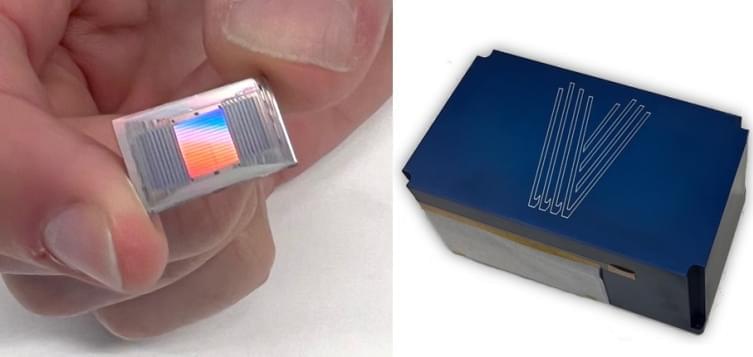

The future of lidar is uncertain unless, as Voyant hopes to do, its price and size are reduced to fractions of their current values. As long as lidars are sandwich-sized devices that cost thousands, they won’t be ubiquitous — so Voyant has raised some cash to bring its smaller, cheaper, more easily manufactured, yet still highly capable lidar to production.

When I wrote up the company’s seed round back in 2019, the goal was more or less to shrink lidar down from sandwich to fingernail size using silicon photonics. But the real challenge faced by nearly every lidar company is getting the price down. Between a strong laser, capable receptor and a mechanical or optical means of directing the beam, it just isn’t easy making something cheap enough that, like an LED or touchscreen, you can easily put several of them in a vehicle that costs less than $30,000.

CEO Peter Stern joined the company just as COVID was getting started, and they were looking for a way to turn a promising prototype developed by co-founders Chris Phare and Steven Miller into a working and marketable product. After going back to basics they ended up with a photonics-based frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) system (just go with it for now) that could be manufactured at existing commercial fabs.