The August skies are going to be gorgeous.

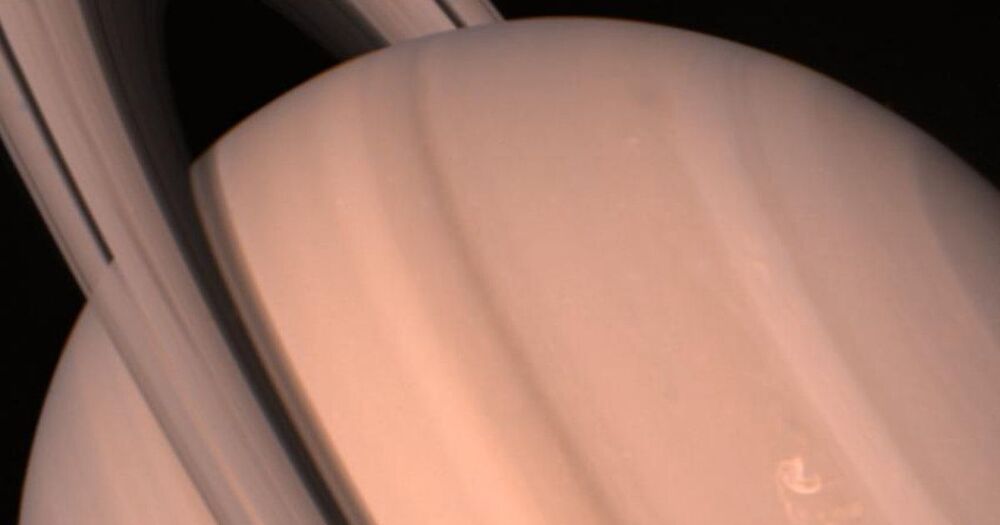

The planet Saturn will reach a moment of alignment with Earth and the Sun known as “opposition” in August 2021 and appear especially bright in the sky.

Skygazers believe they saw a meteor streak across the Texas sky Sunday night.

Update 3:30 p.m. EDT July 26: NASA Meteor Watch confirmed what hundreds of eyewitnesses across the Midwest already knew, that a fireball seen streaking across the night sky was a meteor.

On August 26, 2020, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected a pulse of high-energy radiation that had been racing toward Earth for nearly half the present age of the universe. Lasting only about a second, it turned out to be one for the record books – the shortest gamma-ray burst (GRB) caused by the death of a massive star ever seen.

GRBs are the most powerful events in the universe, detectable across billions of light-years. Astronomers classify them as long or short based on whether the event lasts for more or less than two seconds. They observe long bursts in association with the demise of massive stars, while short bursts have been linked to a different scenario.

Astronomers combined data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, other space missions, and ground-based observatories to reveal the origin of GRB 200826A, a brief but powerful burst of radiation. It’s the shortest burst known to be powered by a collapsing star – and almost didn’t happen at all. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Researchers will use NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to study Beta Pictoris, an intriguing young planetary system that sports at least two planets, a jumble of smaller, rocky bodies, and a dusty disk. Their goals include gaining a better understanding of the structures and properties of the dust to better interpret what is happening in the system. Since it’s only about 63 light-years away and chock full of dust, it appears bright in infrared light – and that means there is a lot of information for Webb to gather.

Beta Pictoris is the target of several planned Webb observing programs, including one led by Chris Stark of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and two led by Christine Chen of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. Stark’s program will directly image the system after blocking the light of the star to gather a slew of new details about its dust. Chen’s programs will gather spectra, which spread light out like a rainbow to reveal which elements are present. All three observing programs will add critical details to what’s known about this nearby system.

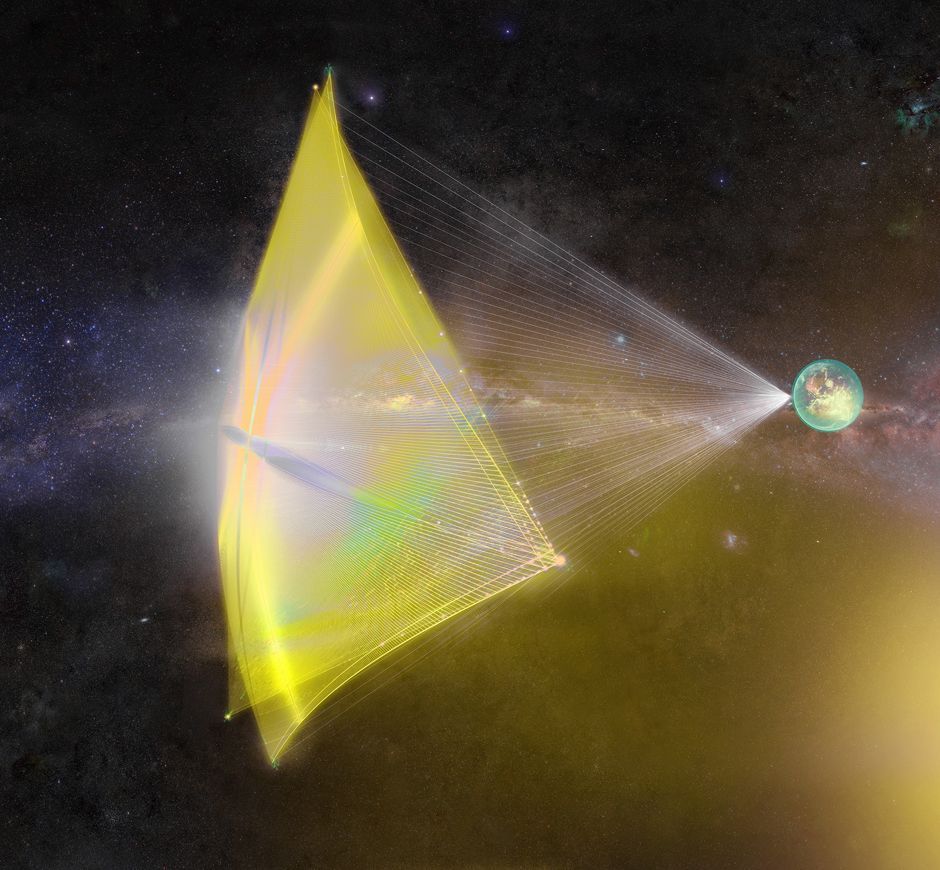

Solar sails have been receiving a lot of attention lately. In part that is due to a series of high profile missions that have successfully proven the concept. It’s also in part due to the high profile Breakthrough Starshot project, which is designing a solar sail powered mission to reach Alpha Centauri. But this versatile third propulsion system isn’t only useful for far flung adventures – it has advantages closer to home as well. A new paper by engineers at UCLA defines what those advantages are, and how we might be able to best utilize them.

The literal driving force behind some solar sail projects are lasers. These concentrated beams of light are perfect to provide a pushing force against a solar sail. However, they are also useful as weapons if scaled up too much, vaporizing anything in its path. As such, one of the main design constraints for solar sail systems is around materials that can withstand a high power laser blast, yet still be light enough to not burden the craft it is attached to with extra weight.

For the missions that graduate student Ho-Ting Tung and Dr. Artur Davoyan of UCLA’s Mechanical Engineering Department envision that weight is miniscule. They expect any sailing spacecraft to weigh less than 100 grams. That 100 grams would include a sail array that measures up to 10 cm square.

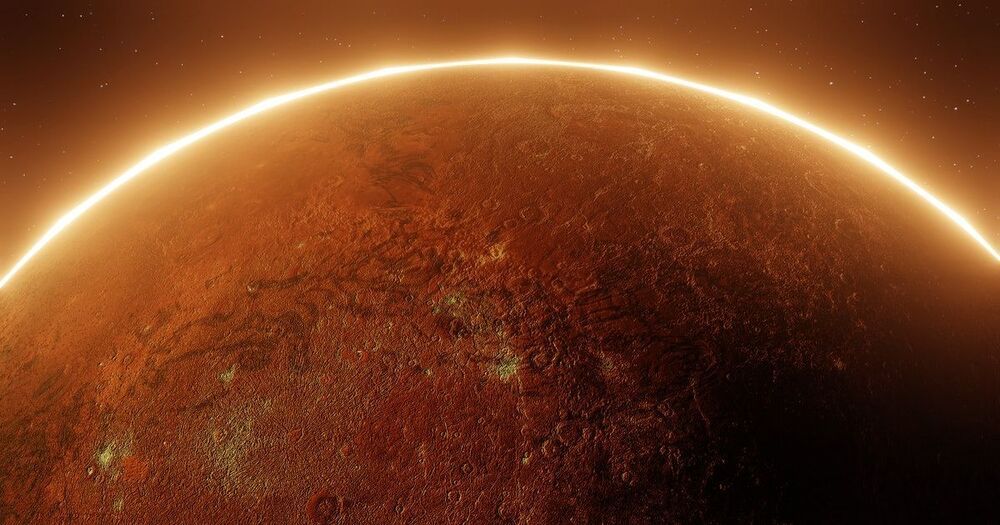

Shortly thereafter, China National Space Agency (CNSA) shared the first images taken by the Tianwen-1 lander.

By May 22, the Zhurong rover descended from its lander and drove on the Martian surface for the first time. Since then, the rover has spent 63 Earth days conducting science operations on the surface of Mars and has traveled over 450 meters (1475 feet).

On Friday, July 9, and again on July 15, the CNSA released new images of the Red Planet that were taken by the rover as it made its way across the surface.

😀

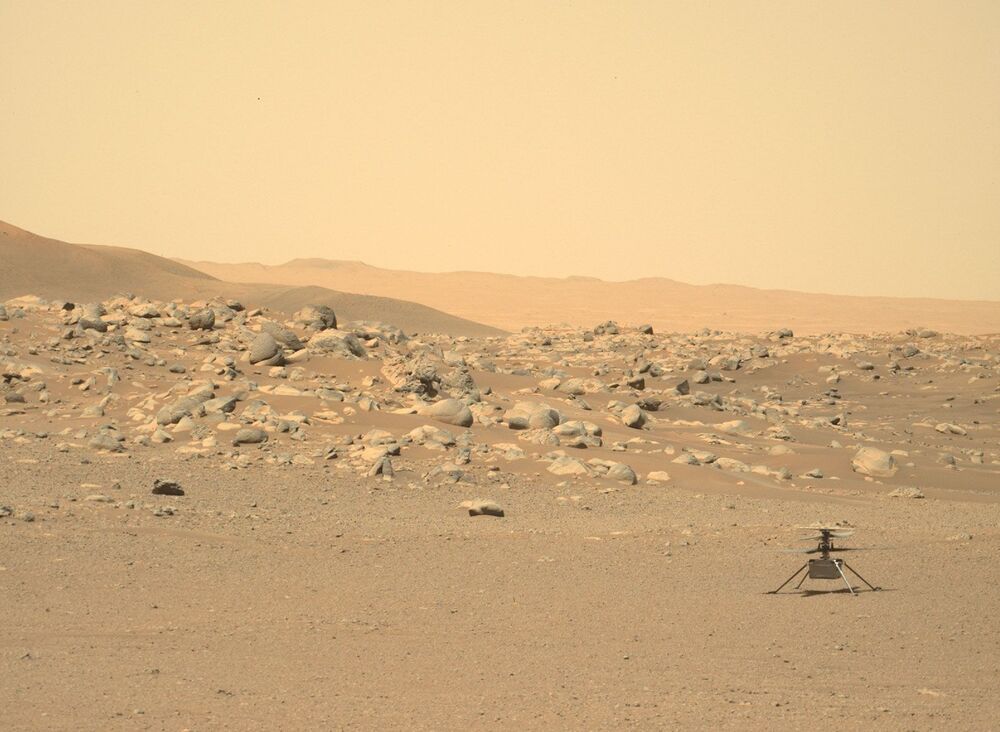

Before Saturday, Ingenuity had already flown nearly one mile in total, so its 10th flight helped it hit that threshold.

The flight should have lasted about 2 minutes, 45 seconds. During that time, Ingenuity is expected to have visited 10 distinct waypoints, snapping photos along the way.

Flight 10 is a significant milestone, since Ingenuity has now flown twice as many times as NASA engineers originally planned. NASA expected Ingenuity to crash on its fourth or fifth flight as it tested the limits of its speed and stamina.

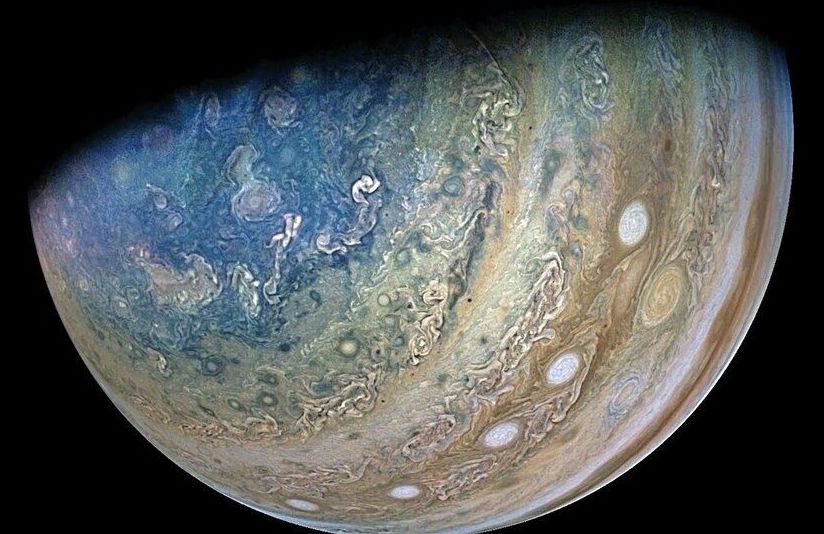

The now iconic spacecraft’s 35th three-hour flyby of Jupiter comes close to the 10th anniversary of its launch. Here are the best and newest phots from its JunoCam imager.