For decades, astronomers weren’t able to find all of the atomic matter in the universe. A series of recent papers has revealed where it’s been hiding.

Playlist Electronic Fusion #158, broadcast on 15 September 2018:

01. Plike — Holmesburg 02. Plike — The Monster Study 03. Plike — Subproject 68 04. Plike — Bluebird 05. Plike — Laboratory 12 (Feat. Digibilly) 06. Alpha Wave Movement — Herzschlag Des Universums 07. Alpha Wave Movement — Other Worlds 08. Chris Gate — This Is Syndae 09. Moonbooter — Syndae’s Theme (Boot From Moon Mix) 10. Stefan Erbe — GP 11. Arend Westra — Under The Milky Way 12. Broekhuis, Keller & Schönwälder — Frozen Nights 13. AndAWan — Time To Remember (Ft. Irene Makri) 14. Thought Guild — Tetrahedral Anomalies 15. Erik Seifert — ALICE (A Large Ion Collider Experiment) 16. Wolfgang Roth (Wolfproject) & Jens-H. Kruhl (Wiesenberg) — The Light Belongs To You.

Someday, people across the world will look back on September 2018, much like we look back on the terror attacks of 9/11 or the safe return of Apollo 13 in 1970. They are touchstone moments in world history. For Americans, they are as indelible as Pearl Harbor, the assassination of John F. Kennedy or the first moon landing.

So, what happened just now? The month isn’t even half over, and the only events we hear about on the news are related to Hurricane Florence and Paul Manafort. (In case you live under a rock or are reading this many years hence, the hurricane made landfall on the coast of the Carolinas, and the lobbyist / political consultant / lawyer / Trump campaign chairman pled guilty to charges and has agreed to cooperate in the continuing Mueller investigation).

No—I am not referring to either event on the USA east coast. I am referring to a saga unfolding 254 miles above the Earth—specifically a Whodunit mystery aboard the International Space Station (ISS). NASA hasn’t seen this level of tawdry intrigue since astronaut Lisa Marie Nowak attacked a rival for another astronaut’s affection—driving across the country in a diaper to confront her love interest.

So What is the Big Deal This Week?!

It didn’t begin as a big deal—and perhaps this is why mainstream news services are slow to pick up on the latest information. But now, in my opinion, it is a very big deal.

A small hole was discovered on a Russian Soyuz spacecraft (a lifeboat) attached to the International Space Station. That hole, about the size of a pea, resulted in the slow decompression of atmosphere. The air that our astronauts breathe was leaking out of ISS and into the void of space.

So far, the story is unremarkable. Ground scientists issued two comfort statements about the apparent accident. They addressed the possible cause and the potential risk:

The initial news event was interesting to space buffs, but it didn’t seem to present a significant threat to our astronauts, nor require a massive technical response. You may recall that duct tape played a critical role in getting the Apollo 13 astronauts safely back to Earth almost 50 years ago. The crisis that they faced was far worse. The solution required extensive impromptu engineering both in Houston and up in the spacecraft. What an awesome historical echo and footnote to an event that captured the hearts and minds of so many people back in 1970.

But the story does not end with a piece of duct tape. In fact, it just got much more interesting…

But the story does not end with a piece of duct tape. In fact, it just got much more interesting…

After a few days, NASA revealed that the hole was intentionally drilled, and the deed probably occurred while the ship was docked at the space station. Since there is no log of activity with tools in this section of the laboratory, it strongly suggests an act of sabotage by one of the astronauts on board.

And now, we have some new information: Guided by ground engineers, astronauts fished an endoscope through the hole to inspect the outside of the spacecraft. Guess what?! That same drill bit damaged the meteorite shield which stands 15 mm beyond the pressurized hull of the spacecraft. This will add significant risk to anyone traveling back to earth in the damaged ship.

Philip Raymond co-chairs CRYPSA, hosts the New York Bitcoin Event and is keynote speaker at Cryptocurrency Conferences. He sits on the New Money Systems board of Lifeboat Foundation and is a top Bitcoin writer at Quora. Book a presentation or consulting engagement.

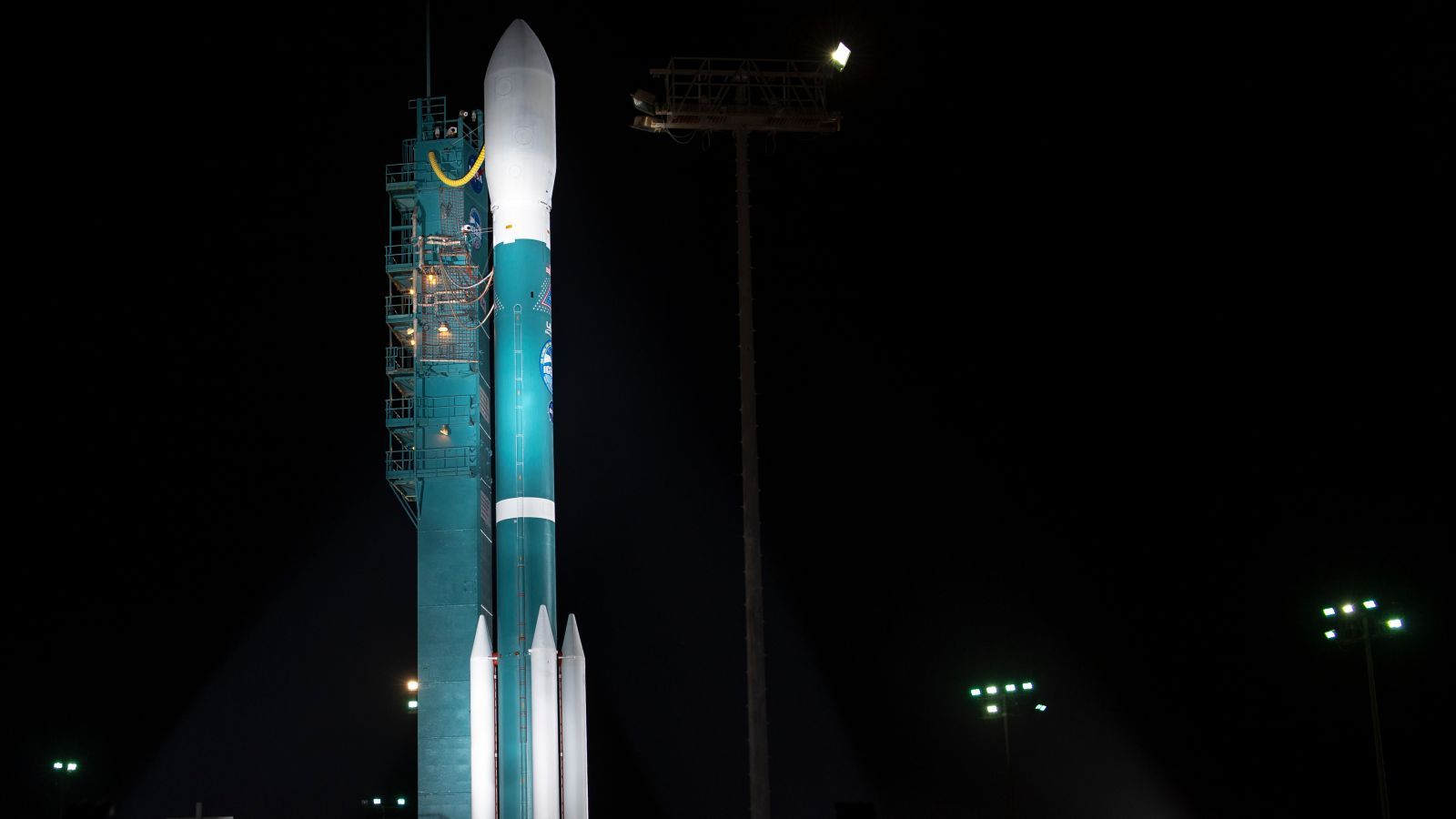

Godspeed, Delta II.

NASA’s last Delta II rocket blasted into the atmosphere from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on Saturday carrying the Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2), Space.com reported, in the rocket’s 155th and final mission.

First entering service in 1989, the Delta II was NASA’s workhorse rocket, with Saturday’s launch capping off 100 successful launches in a row. (The last failure was in 1997, when a Delta II carrying a GPS satellite exploded seconds after leaving the pad.) As noted by the Verge, prior payloads have included the Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes, the Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers, and the original ICESat.

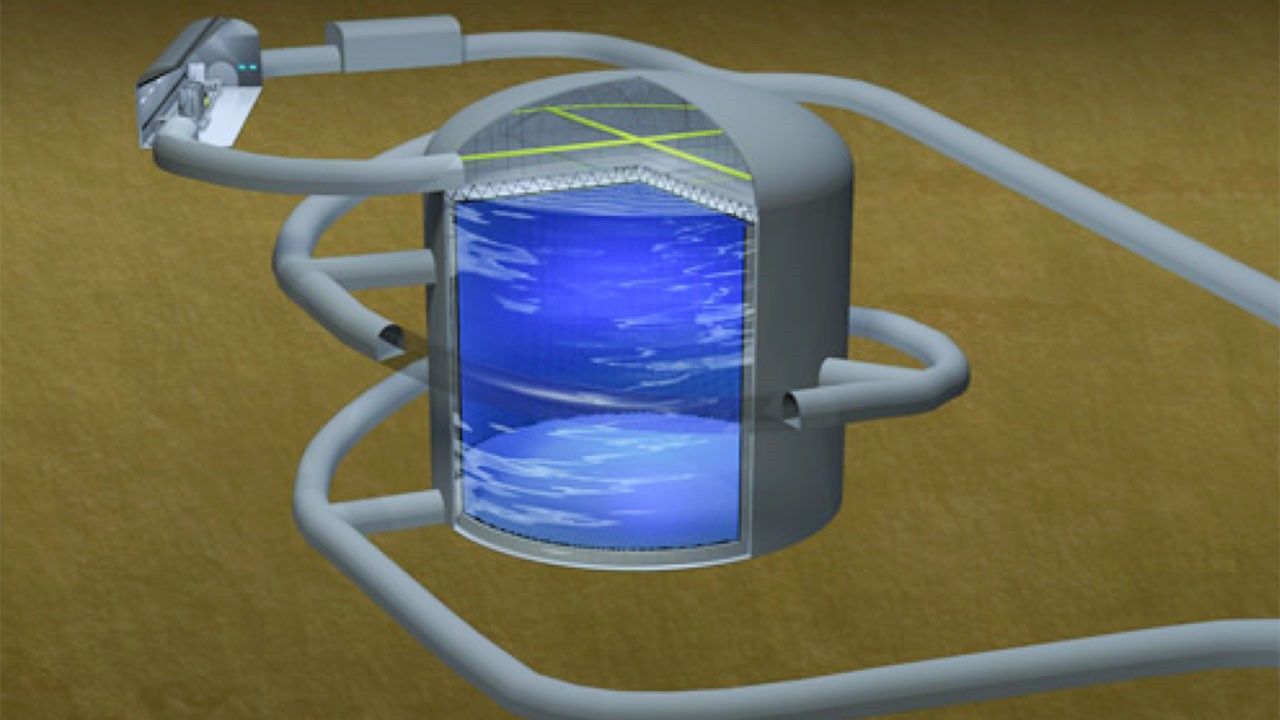

Japan’s government is facing serious fiscal challenges, but its main science ministry appears hopeful that the nation is ready to once again back basic research in a big way. The Ministry of Education (MEXT) on 31 August announced an ambitious budget request that would allow Japan to compete for the world’s fastest supercomputer, build a replacement x-ray space observatory, and push ahead with a massive new particle detector.

Proposed successor to Super-Kamiokande, exascale computer and x-ray satellite win backing.

A few factors were taken into consideration. These included security conditions, climatic conditions at that time of year, the existence of potential scientific partners, and what facilities were available.

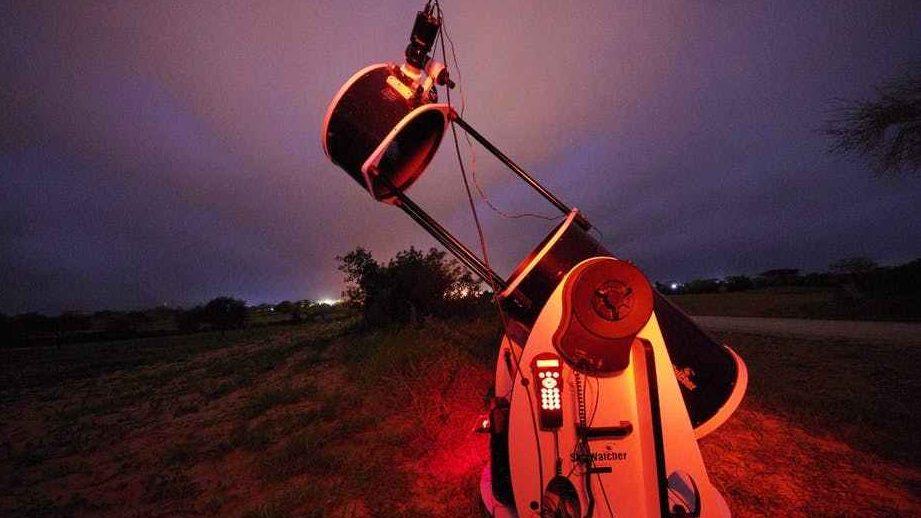

Senegal has made great strides in astronomy and planetary sciences in recent years. That’s been largely driven by the Senegalese Association for the Promotion of Astronomy, led by Maram Kaire. Some Senegalese researchers are also involved in the African Initiative for Planetary and Space Sciences, which I head up.

And so, NASA focused its efforts in Senegal. It sent 21 teams to the country, and six to Columbia, which had less favorable climatic conditions. One team, composed of Algerian astronomers from the Centre de Recherche en Astrophysique et Géophysique, also attempted to observe the occultation in the south of Algeria.

Researchers are paving the way to total reliance on renewable energy as they study both large- and small-scale ways to replace fossil fuels. One promising avenue is converting simple chemicals into valuable ones using renewable electricity, including processes such as carbon dioxide reduction or water splitting. But to scale these processes up for widespread use, we need to discover new electrocatalysts—substances that increase the rate of an electrochemical reaction that occurs on an electrode surface. To do so, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University are looking to new methods to accelerate the discovery process: machine learning.

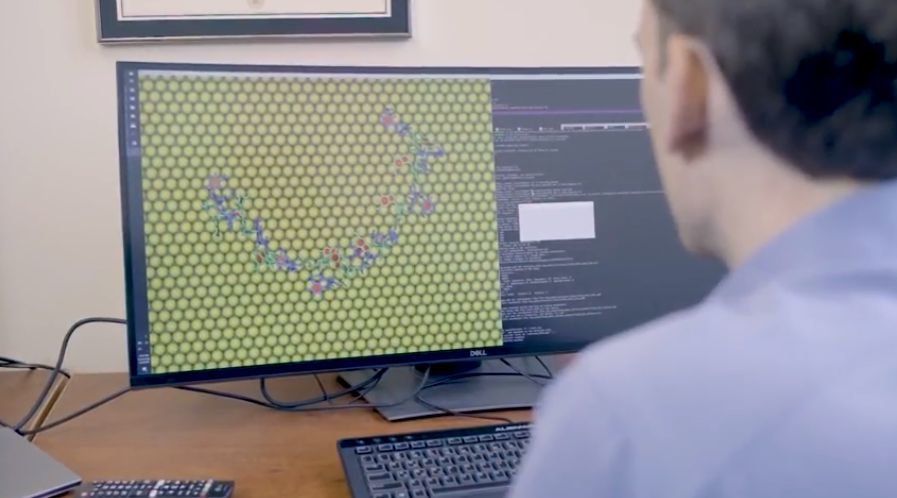

Zack Ulissi, an assistant professor of chemical engineering (ChemE), and his group are using machine learning to guide electrocatalyst discovery. By hand, researchers spend hours doing routine calculations on materials that may not end up working. Ulissi’s team has created a system that automates these routine calculations, explores a large search space, and suggests new alloys that have promising properties for electrocatalysis.

“This allows us to spend our time asking science questions, like, ‘How do you predict the properties of something,’ ‘What is the thermodynamic model,’ ‘What is the model of the system,’ or ‘How do you represent the system?’” said Ulissi.

Engineers at the University of Maryland have created a thin battery, made of a few million carefully constructed “microbatteries” in a square inch. Each microbattery is shaped like a very tall, round room, providing much surface area – like wall space – on which nano-thin battery layers are assembled. The thin layers together with large surface area produces very high power along with high energy. It is dubbed a “3D battery” because each microbattery has a distinctly 3D shape.

These 3D batteries push conventional planar thin-film solid state batteries into a third dimension. Planar batteries are a single stack of flat layers serving the roles of anode, electrolyte, cathode and current collectors.

But to make the 3D batteries, the researchers drilled narrow holes are formed in silicon, no wider than a strand of spider silk but many times deeper. The battery materials were coated on the interior walls of the deep holes. The increased wall surface of the 3D microbatteries provides increased energy, while the thinness of the layers dramatically increases the power that can be delivered. The process is a little more complicated and expensive than its flat counterpart, but leads to more energy and higher power in the same footprint.

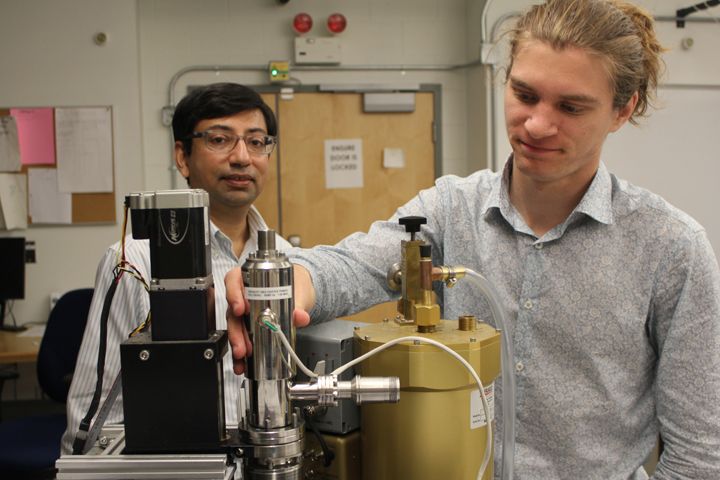

A recent discovery by William & Mary and University of Michigan researchers transforms our understanding of one of the most important laws of modern physics. The discovery, published in the journal Nature, has broad implications for science, impacting everything from nanotechnology to our understanding of the solar system.

“This changes everything, even our ideas about planetary formation,” said Mumtaz Qazilbash, associate professor of physics at William & Mary and co-author on the paper. “The full extent of what this means is an important question and, frankly, one I will be continuing to think about.”

Qazilbash and two W&M graduate students, Zhen Xing and Patrick McArdle, were asked by a team of engineers from the University of Michigan to help them test whether Planck’s radiation law, a foundational scientific principle grounded in quantum mechanics, applies at the smallest length scales.