We finally have clear photos of the mysterious substance that China found on the far side of the Moon.

China’s Yutu 2 rover came across the shiny material in July, and the new photo may give us a better idea about what it could be.

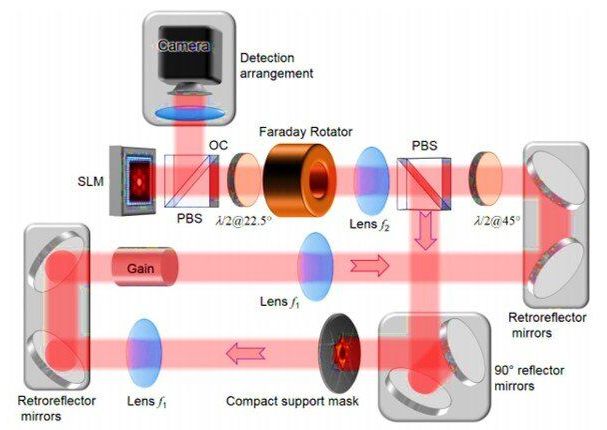

Physicists can explore tailored physical systems to rapidly solve challenging computational tasks by developing spin simulators, combinatorial optimization and focusing light through scattering media. In a new report on Science Advances, C. Tradonsky and a group of researchers in the Departments of Physics in Israel and India addressed the phase retrieval problem by reconstructing an object from its scattered intensity distribution. The experimental process addressed an existing problem in disciplines ranging from X-ray imaging to astrophysics that lack techniques to reconstruct an object of interest, where scientists typically use indirect iterative algorithms that are inherently slow.

In the new optical approach, Tradonsky et al conversely used a digital degenerate cavity laser (DDCL) mode to rapidly and efficiently reconstruct the object of interest. The experimental results suggested that the gain competition between the many lasing modes acted as a highly parallel computer to rapidly dissolve the phase retrieval problem. The approach applies to two-dimensional (2-D) objects with known compact support and complex-valued objects, to generalize imaging through scattering media, while accomplishing other challenging computational tasks.

To calculate the intensity distribution of light scattered far from an unknown object relatively easily, researchers can compute the source of the absolute value of an object’s Fourier transform. The reconstruction of an object from its scattered intensity distribution is, however, ill-posed, since phase information can be lost and diverse phase distributions in the work can result in different reconstructions. Scientists must therefore obtain prior information about an object’s shape, positivity, spatial symmetry or sparsity for more precise object reconstructions. Such examples are found in astronomy, short-pulse characterization studies, X-ray diffraction, radar detection, speech recognition and when imaging across turbid media. During the reconstruction of objects with a finite extent (compact support), researchers offer a unique solution to the phase retrieval problem, as long as they model the same scattered intensity at a sufficiently higher resolution.

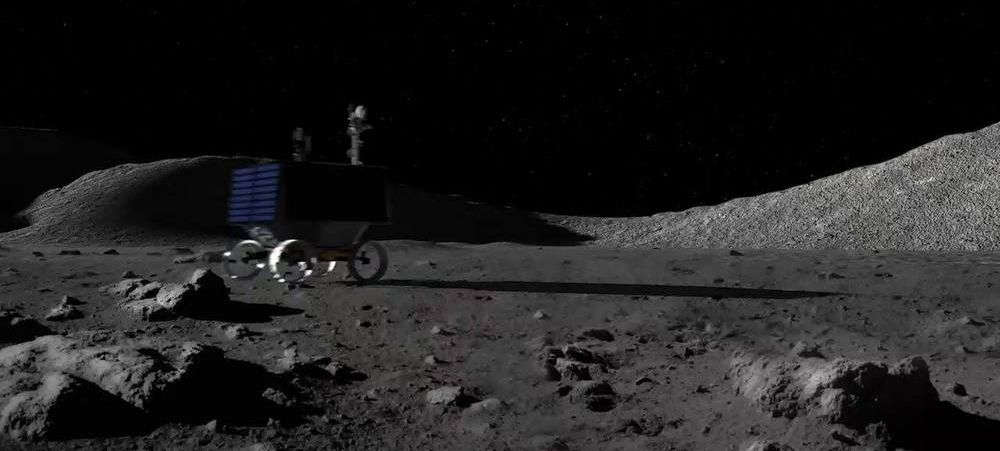

In 2022, we’ll send a rover to hunt for water at the lunar south pole. Learn more about our VIPER mission and how its findings will bring us closer to establishing a sustainable presence on the Moon: https://go.nasa.gov/2WcDtCQ

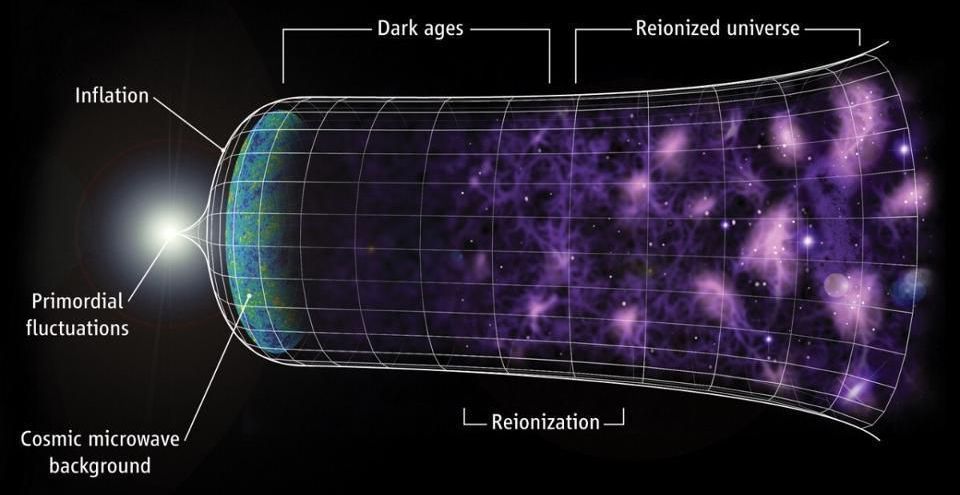

Many of the most dramatic events in the solar system—the spectacle of the Northern Lights, the explosiveness of solar flares, and the destructive impact of geomagnetic storms that can disrupt communication and electrical grids on Earth—are driven in part by a common phenomenon: fast magnetic reconnection. In this process the magnetic field lines in plasma—the gas-like state of matter consisting of free electrons and atomic nuclei, or ions—tear, come back together and release large amounts of energy (Figure 1).

Astrophysicists have long puzzled over whether this mechanism can occur in the cold, relatively dense regions of interstellar space outside the solar system where stars are born. Such regions are filled with partially ionized plasma, a mix of free charged electrons and ions and the more familiar neutral, or whole, atoms of gas. If magnetic reconnection does occur in these regions it might dissipate magnetic fields and stimulate star formation.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have developed a model and simulation that show the potential for reconnection to occur in interstellar space.

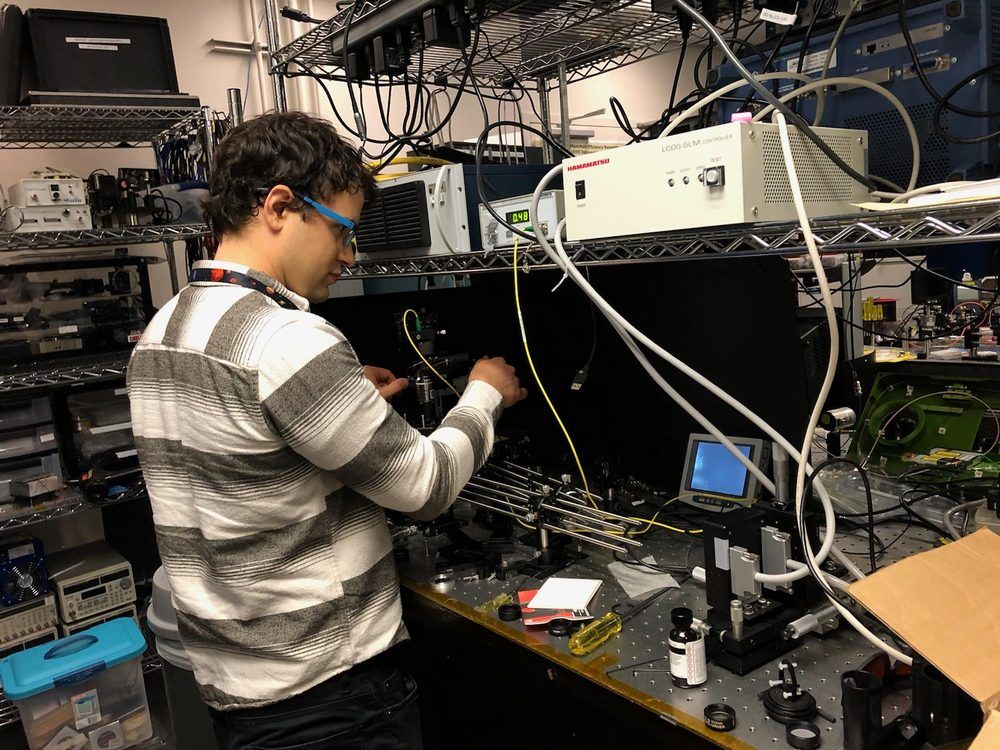

On a metal workbench covered with tools, instruments, cords, and bottles of solution, Aaron Yevick is using laser light to create a force field with which to move particles of matter.

Yevick is an optical engineer who came to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, full-time earlier this year. Despite being in his current position with NASA less than a year, Yevick received funding from the Goddard Fellows Innovation Challenge (GFIC) — a research and development program focused on supporting riskier, less mature technologies — to advance his work.

His goal is to fly the technology aboard the International Space Station, where astronauts could experiment with it in microgravity. Eventually, he believes the technology could help researchers explore other planets, moons, and comets by helping them collect and study samples.