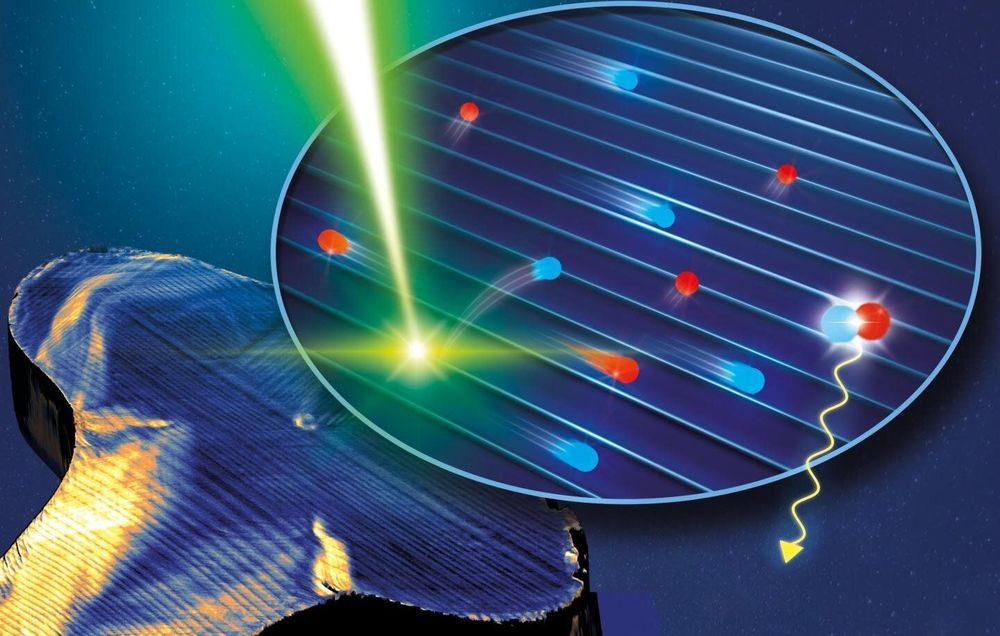

Spiders produce amazingly strong and lightweight threads called draglines that are made from silk proteins. Although they can be used to manufacture a number of useful materials, getting enough of the protein is difficult because only a small amount can be produced by each tiny spider. In a new study published in Communications Biology, a research team led by Keiji Numata at the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science (CSRS) reported that they succeeded in producing the spider silk using photosynthetic bacteria. This study could open a new era in which photosynthetic bio-factories stably output the bulk of spider silk.

In addition to being tough and lightweight, silks derived from arthropod species are biodegradable and biocompatible. In particular, spider silk is ultra-lightweight and is as tough as steel. “Spider silk has the potential to be used in the manufacture of high-performance and durable materials such as tear-resistant clothing, automobile parts, and aerospace components,” explains Choon Pin Foong, who conducted this study. “Its biocompatibility makes it safe for use in biomedical applications such as drug delivery systems, implant devices, and scaffolds for tissue engineering.” Because only a trace amount can be obtained from one spider, and because breeding large numbers of spiders is difficult, attempts have been made to produce artificial spider silk in a variety of species.

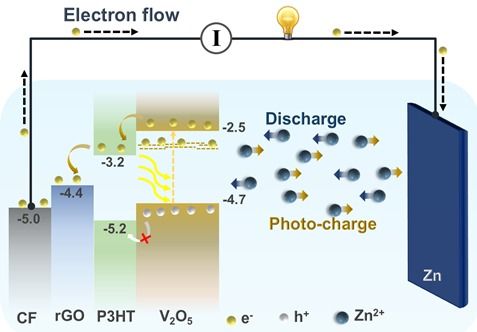

The CSRS team focused on the marine photosynthetic bacterium Rhodovulum sulfidophilum. This bacterium is ideal for establishing a sustainable bio-factory because it grows in seawater, requires carbon dioxide and nitrogen in the atmosphere, and uses solar energy, all of which are abundant and inexhaustible.