Kindly see my latest FORBES article on technology predictions for the next decade:

Thanks and have a great weekend! Chuck Brooks.

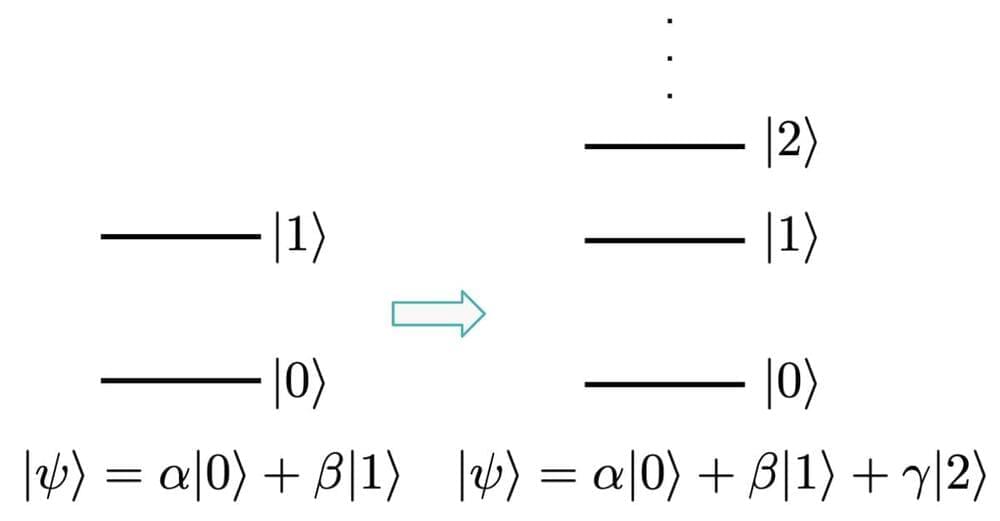

We are approaching 2022 and rather than ponder the immediate future, I want to explore what may beckon in the ecosystem of disruptive technologies a decade from now. We are in the initial stages of an era of rapid and technological change that will witness regeneration of body parts, new cures for diseases, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, human/computer interface, autonomous vehicles, advanced robotics, flying cars, quantum computing, and connected smart cities. Exciting times may be ahead.

By 2032, it will be logical to assume that the world will be amid a digital and physical transformation beyond our expectations. It is no exaggeration to say we are on the cusp of scientific and technological advancements that will change how we live and interact.

What should we expect in the coming decade as we begin 2022? While there are many potential paradigms changing technological influences that will impact the future, let us explore three specific categories of future transformation: cognitive computing, health and medicine, and autonomous everything.