Breakthrough will help with the development of reliable quantum computers.

DENVER — Researchers have developed a new, unspeakably dangerous, and incredibly slow method of crossing the universe. It involves wormholes linking special black holes that probably don’t exist. And it might explain what’s really going on when physicists quantum-teleport information from one point to another — from the perspective of the teleported bit of information.

Daniel Jafferis, a Harvard University physicist, described the proposed method at a talk April 13 here at a meeting of the American Physical Society. This method, he told his assembled colleagues, involves two black holes that are entangled so that they are connected across space and time.

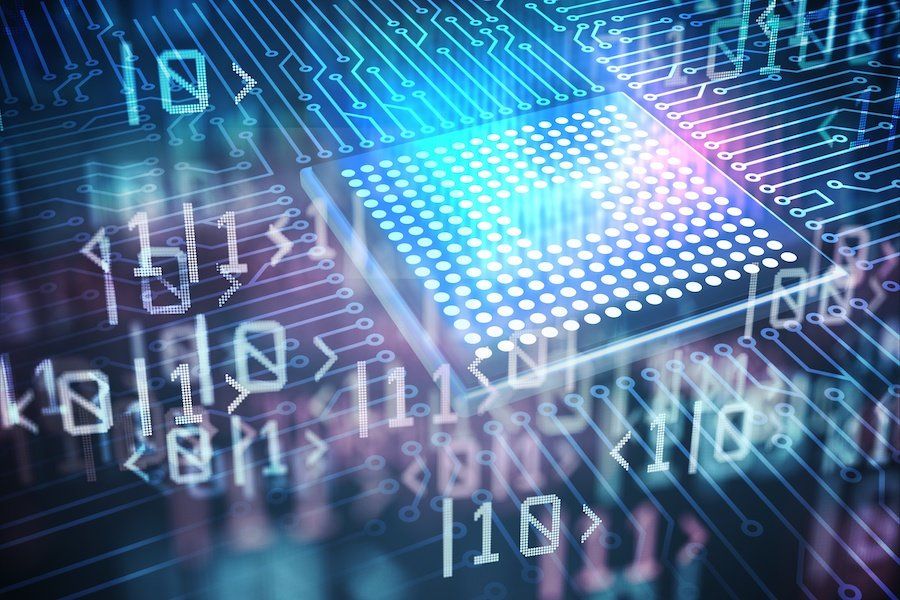

With a quantum coprocessor in the cloud, physicists from Innsbruck, Austria, open the door to the simulation of previously unsolvable problems in chemistry, materials research or high-energy physics. The research groups led by Rainer Blatt and Peter Zoller report in the journal Nature how they simulated particle physics phenomena on 20 quantum bits and how the quantum simulator self-verified the result for the first time.

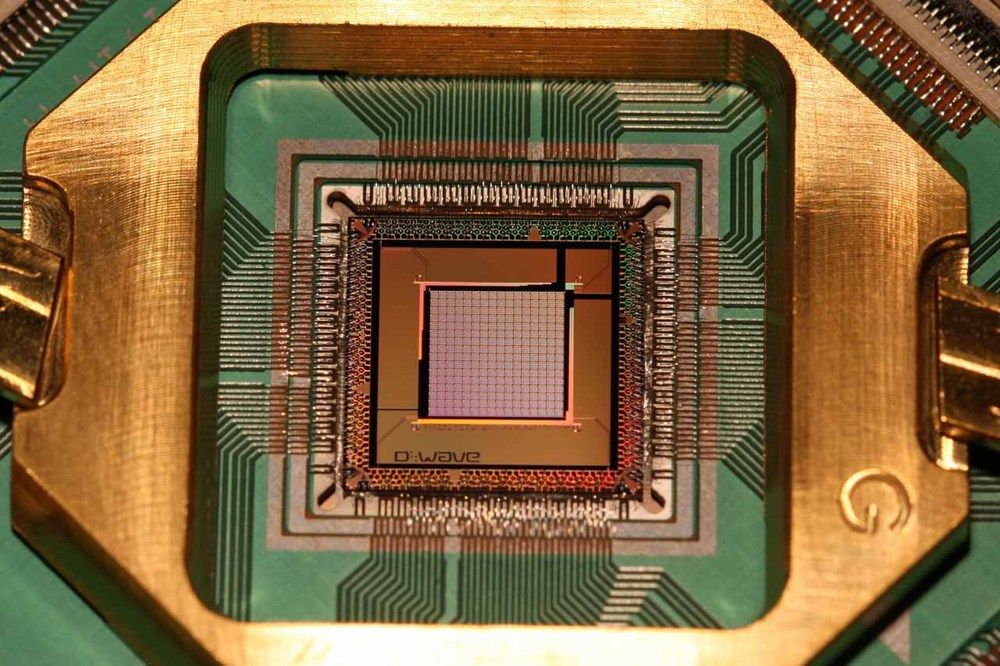

Many scientists are currently working on investigating how quantum advantage can be exploited on hardware already available today. Three years ago, physicists first simulated the spontaneous formation of a pair of elementary particles with a digital quantum computer at the University of Innsbruck. Due to the error rate, however, more complex simulations would require a large number of quantum bits that are not yet available in today’s quantum computers. The analog simulation of quantum systems in a quantum computer also has narrow limits. Using a new method, researchers around Christian Kokail, Christine Maier und Rick van Bijnen at the Institute of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information (IQOQI) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences have now surpassed these limits. They use a programmable ion trap quantum computer with 20 quantum bits as a quantum coprocessor, in which quantum mechanical calculations that reach the limits of classical computers are outsourced.

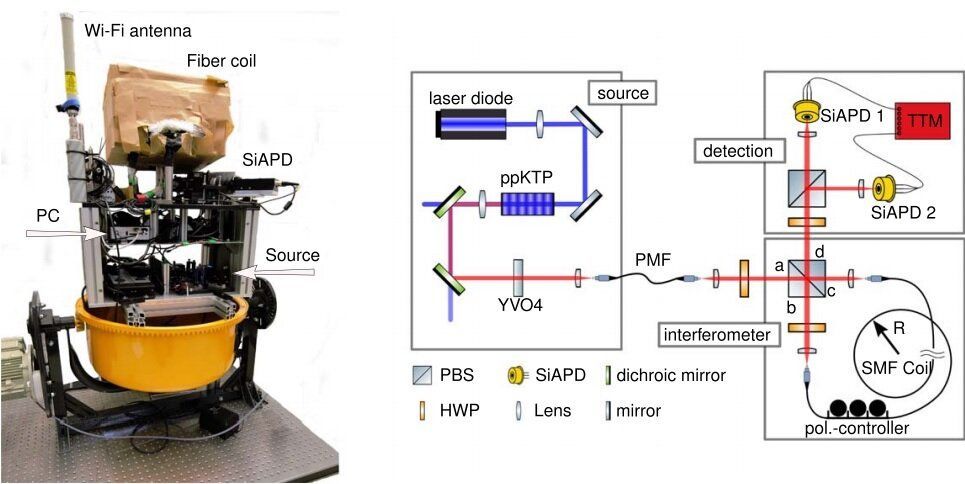

Fiber optic gyroscopes, which measure the rotation and orientation of airplanes and other moving objects, are inherently limited in their precision when using ordinary classical light. In a new study, physicists have experimentally demonstrated for the first time that using entangled photons overcomes this classical limit, called the shot-noise limit, and achieves a level of precision that would not be possible with classical light.

The physicists, led by Matthias Fink and Rupert Ursin at the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Vienna Center for Quantum Science and Technology, have published a paper on the entanglement-enhanced fiber-optic gyroscope in a recent issue of the New Journal of Physics.

“We have demonstrated that the generation of entangled photons has reached a level of technical maturity that enables us to perform measurements with sub-shot noise accuracy in harsh environments,” Fink told Phys.org.

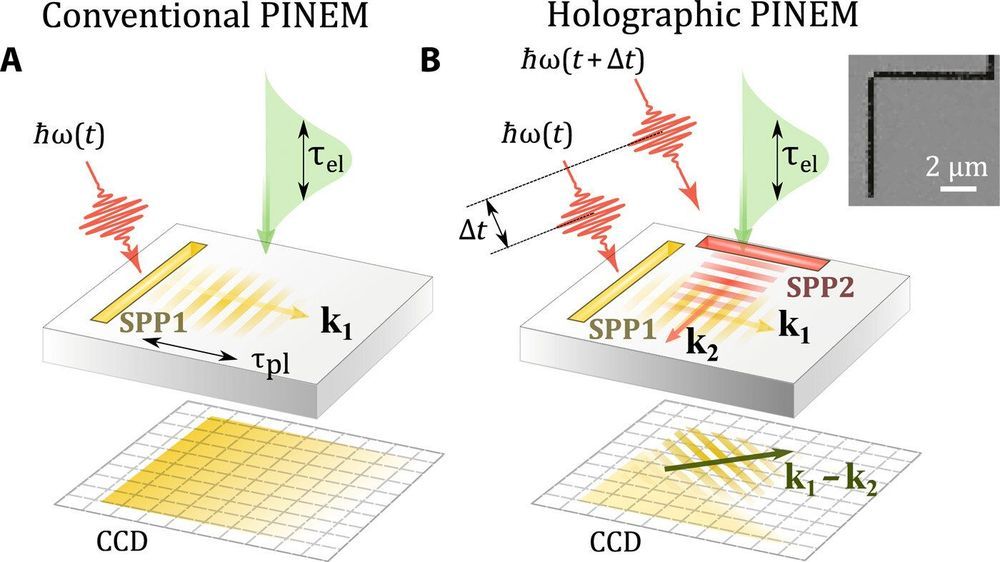

In conventional holography a photographic film can record the interference pattern of monochromatic light scattered from the object to be imaged with a reference beam of un-scattered light. Scientists can then illuminate the developed image with a replica of the reference beam to create a virtual image of the original object. Holography was originally proposed by the physicist Dennis Gabor in 1948 to improve the resolution of an electron microscope, demonstrated using light optics. A hologram can be formed by capturing the phase and amplitude distribution of a signal by superimposing it with a known reference. The original concept was followed by holography with electrons, and after the invention of lasers optical holography became a popular technique for 3D imaging macroscopic objects, information encryption and microscopy imaging.

However, extending holograms to the ultrafast domain currently remains a challenge with electrons, although developing the technique would allow the highest possible combined spatiotemporal resolution for advanced imaging applications in condensed matter physics. In a recent study now published in Science Advances, Ivan Madan and an interdisciplinary research team in the departments of Ultrafast Microscopy and Electron Scattering, Physics, Science and Technology in Switzerland, the U.K. and Spain, detailed the development of a hologram using local electromagnetic fields. The scientists obtained the electromagnetic holograms with combined attosecond/nanometer resolution in an ultrafast transmission electron microscope (UEM).

In the new method, the scientists relied on electromagnetic fields to split an electron wave function in a quantum coherent superposition of different energy states. The technique deviated from the conventional method, where the signal of interest and reference spatially separated and recombined to reconstruct the amplitude and phase of a signal of interest to subsequently form a hologram. The principle can be extended to any kind of detection configuration involving a periodic signal capable of undergoing interference, including sound waves, X-rays or femtosecond pulse waveforms.