Microsoft, Alphabet and Brilliant are offering a course that teaches you the ins and outs of quantum computer coding.

Quantum physics, the study of the universe on an atomic scale, gives us a reference model to understand the human ecosystem in the discrete individual unit. It helps us understand how individual human behavior impacts collective systems and the security of humanity.

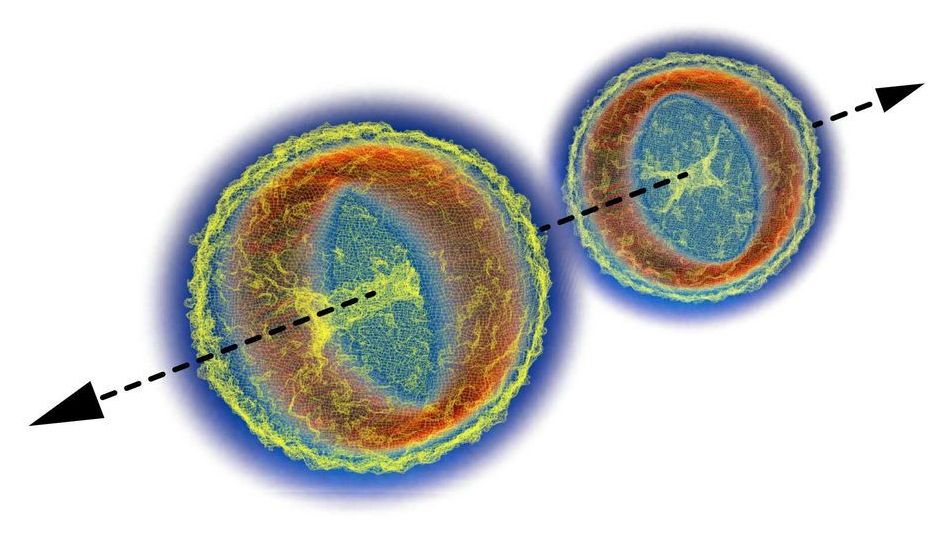

Metaphorically, we can see this in how a particle can act both like a particle or a wave. The concept of entanglement is at the core of much of applied quantum physics. The commonly understood definition of entanglement says that particles can be generated to have a distinct reliance on each other, despite any three-dimensional or 4-dimensional distance between the particles. What this definition and understanding imply is that even if two or more particles are physically detached with no traditional or measurable linkages, what happens to one still has a quantifiable effect on the other.

Now, individuals and entities across NGIOA are part of an entangled global system. Since the ability to generate and manipulate pairs of entangled particles is at the foundation of many quantum technologies, it is important to understand and evaluate how the principles of quantum physics translate to the survival and security of humanity.

Quantum computing’s processing power could begin to improve artificial-intelligence systems within about five years, experts and business leaders said.

For example, a quantum computer could develop AI-based digital assistants with true contextual awareness and the ability to fully understand interactions with customers, said Peter Chapman, chief executive of quantum-computing startup IonQ Inc.

“Today, people are frustrated when a digital assistant says, ‘Sorry, I couldn’t understand that,’” said Mr. Chapman, who was named CEO of the venture-capital-backed startup this week after about five years as director of engineering for Amazon.com Inc.’s Amazon Prime. Quantum computers “could alleviate those problems,” he said.

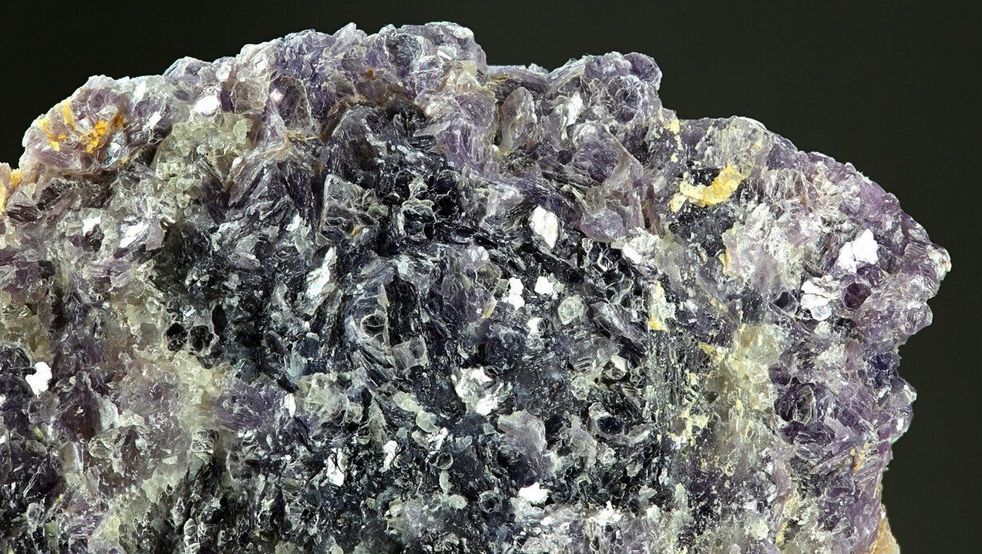

Using cutting-edge theoretical calculations performed at NERSC, researchers at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry have predicted fascinating new properties of lithium—a light alkali metal that has intrigued scientists for two decades with its remarkable diversity of physical states at high pressures.

“Under standard conditions, lithium is a simple metal that forms a textbook crystalline solid. However, scientists have shown that when you put a lithium crystal under pressure, the atomic structure changes and, somewhat counterintuitively, its conductivity drops, becoming less metallic,” said Stephanie Mack, a graduate student research assistant at Berkeley Lab and first author of the study, published in PNAS. “We’ve discovered it also becomes topological, with electronic properties similar to graphene.”

Topological materials are a recently discovered class of solids that display exotic properties, such as having insulating interiors yet highly conductive surfaces, even when deformed. They are exciting for potential applications in next-generation electronics and quantum information science. According to coauthors Sinéad Griffin and Jeff Neaton, lithium becomes topological at high but experimentally achievable pressures, comparable to one-quarter of the pressure at the Earth’s center.

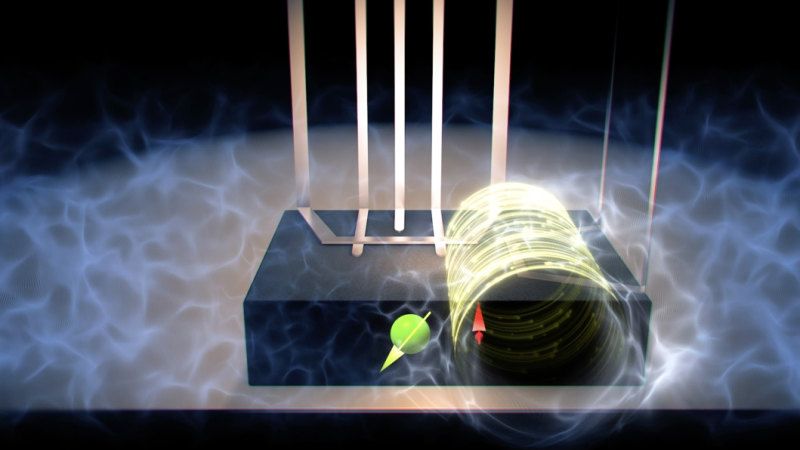

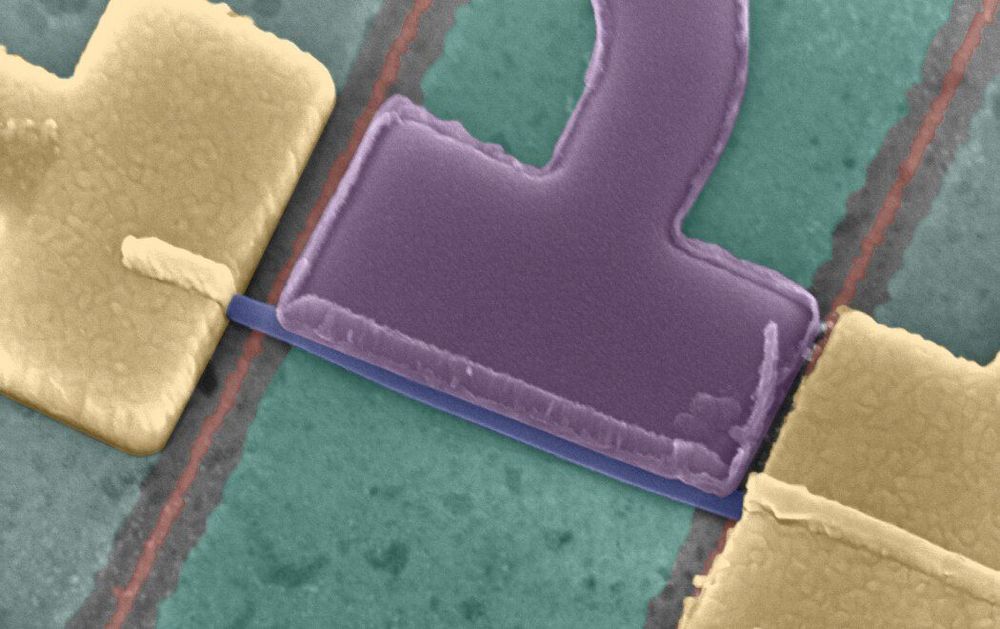

Researchers at Delft University of Technology have recently carried out a study investigating spin-orbit interaction in Majorana nanowires. Their study, published in Physical Review Letters, is the first to clearly show the mechanism that enables the creation of the elusive Majorana particle, which could become the building block of a more stable type of quantum computer.

“Our research is aimed at experimental verification of the theoretically proposed Majorana zero-mode,” Jouri Bommer, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org via email. “This particle, which is its own antiparticle, is of particular interest, because it is predicted to be useful for developing a topological quantum computer.”

Quantum computing is a promising area of computer science that explores the use of quantum-mechanical phenomena and quantum states to store information and solve computational problems. In the future, quantum computers could tackle problems that traditional computing methods are unable to solve, for instance enabling the computational and deterministic design of new drugs and molecules.

A technique to stabilise alkali metal vapour density using gold nanoparticles, so electrons can be accessed for applications including quantum computing, atom cooling and precision measurements, has been patented by scientists at the University of Bath.

Alkali metal vapours, including lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium and caesium, allow scientists to access individual electrons, due to the presence of a single electron in the outer ‘shell’ of alkali metals.

This has great potential for a range of applications, including logic operations, storage and sensing in quantum computing, as well as in ultra-precise time measurements with atomic clocks, or in medical diagnostics including cardiograms and encephalograms.

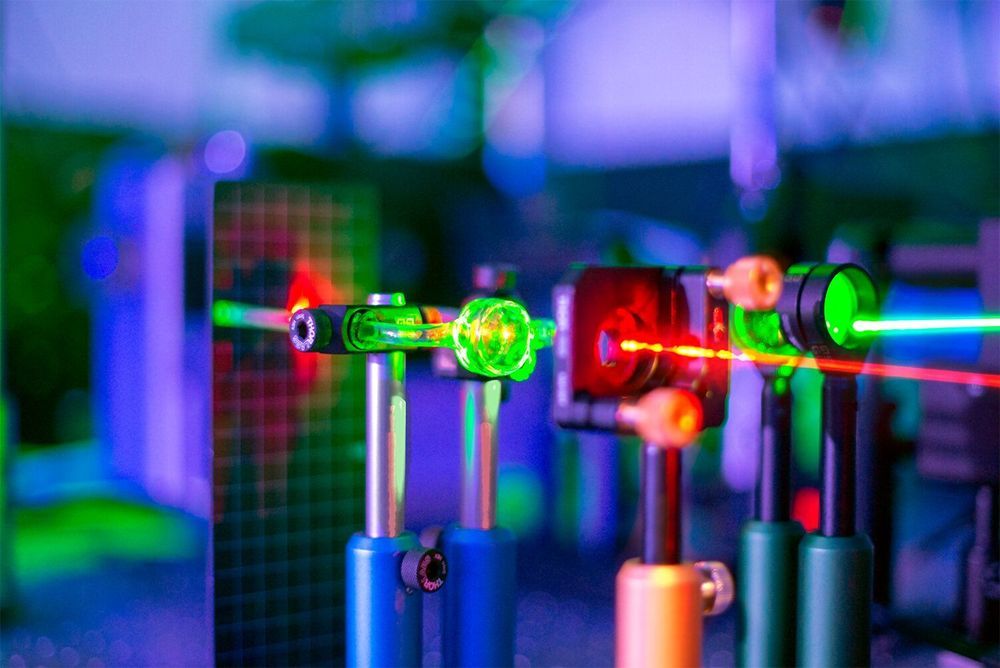

A new idea for smashing beams of elementary particles into one another could reveal how light and matter interact under extreme conditions that may exist on the surfaces of exotic astrophysical objects, in powerful cosmic light bursts and star explosions, in next-generation particle colliders and in hot, dense fusion plasma.

Most such interactions in nature are very successfully described by a theory known as quantum electrodynamics (QED). However, the current form of the theory doesn’t help predict phenomena in extremely large electromagnetic fields. In a recent paper in Physical Review Letters, researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and their colleagues have suggested a new particle collider concept that would allow us to study these extreme effects.

Extreme fields sap energy from colliding particle beams—an unwanted loss that is typically mitigated by bundling particles into relatively long, flat bunches and keeping the electromagnetic field strength in check. Instead, the new study suggests making particle bunches so short that they wouldn’t have enough time to lose energy. Such a collider would provide an opportunity to study intriguing effects associated with extreme fields, including the collision of photons emerging from the particle beams.