Xanadu, the quantum computing startup known for PennyLane and Strawberry Fields, has launched its photonics quantum computing platform.

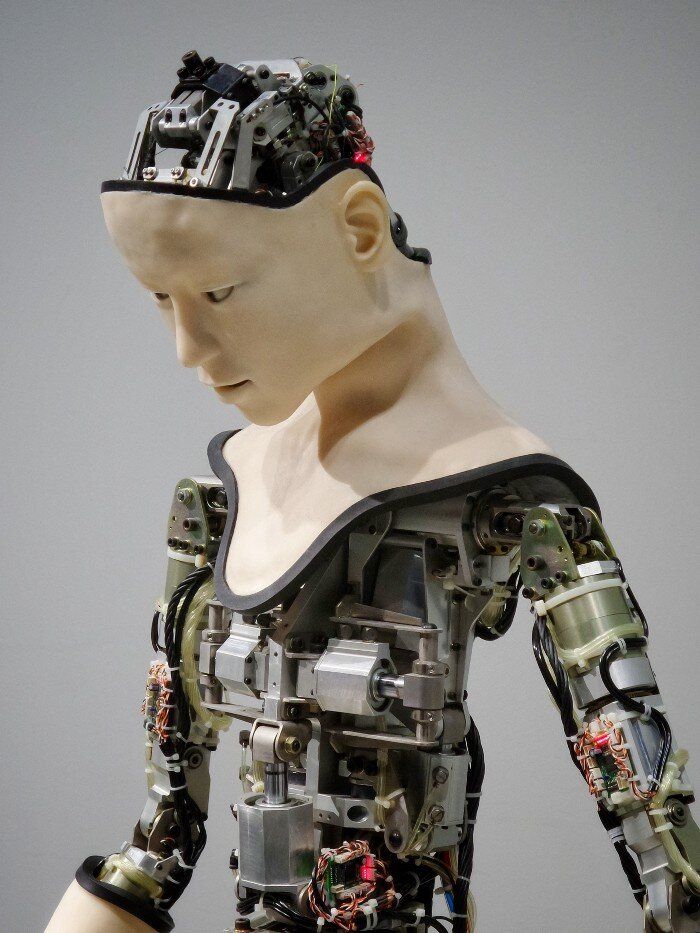

The technology behind the quantum computers of the future is fast developing, with several different approaches in progress. Many of the strategies, or “blueprints,” for quantum computers rely on atoms or artificial atom-like electrical circuits. In a new theoretical study in the journal Physical Review X, a group of physicists at Caltech demonstrates the benefits of a lesser-studied approach that relies not on atoms but molecules.

“In the quantum world, we have several blueprints on the table and we are simultaneously improving all of them,” says lead author Victor Albert, the Lee A. DuBridge Postdoctoral Scholar in Theoretical Physics. “People have been thinking about using molecules to encode information since 2001, but now we are showing how molecules, which are more complex than atoms, could lead to fewer errors in quantum computing.”

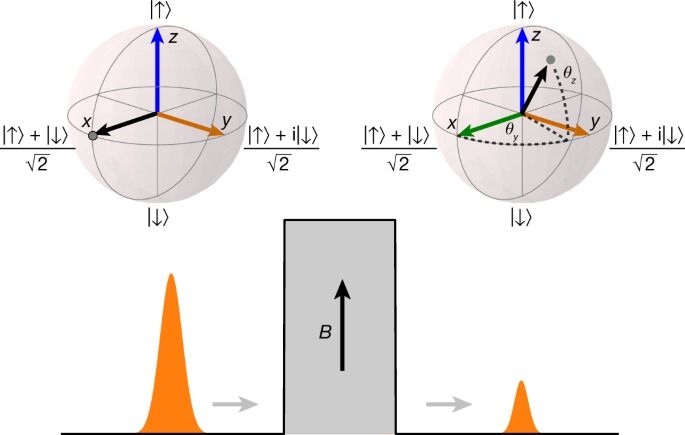

At the heart of quantum computers are what are known as qubits. These are similar to the bits in classical computers, but unlike classical bits they can experience a bizarre phenomenon known as superposition in which they exist in two states or more at once. Like the famous Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment, which describes a cat that is both dead and alive at the same time, particles can exist in multiple states at once. The phenomenon of superposition is at the heart of quantum computing: the fact that qubits can take on many forms simultaneously means that they have exponentially more computing power than classical bits.

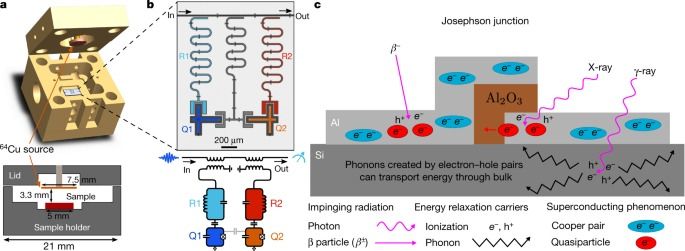

Technologies that rely on quantum bits (qubits) require long coherence times and high-fidelity operations1. Superconducting qubits are one of the leading platforms for achieving these objectives2,3. However, the coherence of superconducting qubits is affected by the breaking of Cooper pairs of electrons4,5,6. The experimentally observed density of the broken Cooper pairs, referred to as quasiparticles, is orders of magnitude higher than the value predicted at equilibrium by the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer theory of superconductivity7,8,9. Previous work10,11,12 has shown that infrared photons considerably increase the quasiparticle density, yet even in the best-isolated systems, it remains much higher10 than expected, suggesting that another generation mechanism exists13. Here we provide evidence that ionizing radiation from environmental radioactive materials and cosmic rays contributes to this observed difference. The effect of ionizing radiation leads to an elevated quasiparticle density, which we predict would ultimately limit the coherence times of superconducting qubits of the type measured here to milliseconds. We further demonstrate that radiation shielding reduces the flux of ionizing radiation and thereby increases the energy-relaxation time. Albeit a small effect for today’s qubits, reducing or mitigating the impact of ionizing radiation will be critical for realizing fault-tolerant superconducting quantum computers.

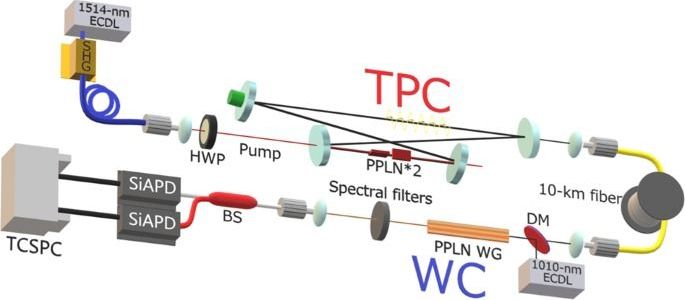

Quantum technologies have seen a remarkable development in recent years and are expected to contribute to quantum internet technologies. The authors present an experimental implementation over commercial telecom fibres of a two-photon comb source for quantum communications with long coherence times and narrow bandwidth, which is used in a 20 km distribution experiment to show the presence of remote two-photon correlations.

AI has found religion.

Or at least one engineer and quantum researcher has brought a bit of religion to his AI project.

George Davila Durendal fed the entire text of the King James Bible into his algorithms designed to churn out dialogue in the style of the Old Testament.

Durendal claimed his project, AI Jesus, learned and absorbed “every word more thoroughly than all the monks of all the monasteries that have ever been,” offering a little biblical style verse of his own.

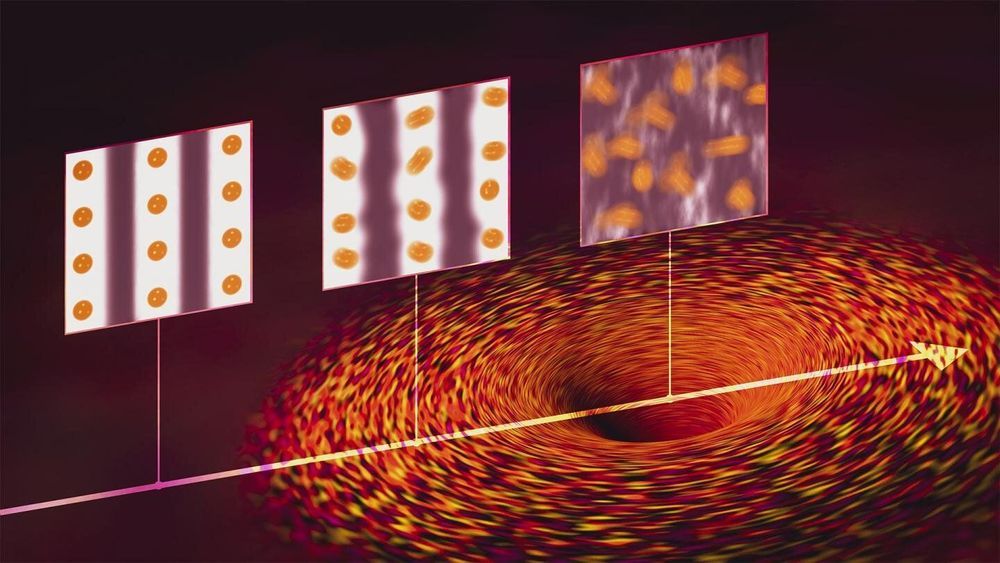

Among all the curious states of matter that can coexist in a quantum material, jostling for preeminence as temperature, electron density and other factors change, some scientists think a particularly weird juxtaposition exists at a single intersection of factors, called the quantum critical point or QCP.

“Quantum critical points are a very hot issue and interesting for many problems,” says Wei-Sheng Lee, a staff scientist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES). “Some suggest that they’re even analogous to black holes in the sense that they are singularities—point-like intersections between different states of matter in a quantum material—where you can get all sorts of very strange electron behavior as you approach them.”

Lee and his collaborators reported in Nature Physics today that they have found strong evidence that QCPs and their associated fluctuations exist. They used a technique called resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) to probe the electronic behavior of a copper oxide material, or cuprate, that conducts electricity with perfect efficiency at relatively high temperatures.

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound? Perhaps not, some say.

And if someone is there to hear it? If you think that means it obviously did make a sound, you might need to revise that opinion.

We have found a new paradox in quantum mechanics – one of our two most fundamental scientific theories, together with Einstein’s theory of relativity – that throws doubt on some common-sense ideas about physical reality.

The White House on Wednesday will announce that federal agencies and their private sector partners are committing more than $1 billion over the next five years to establish 12 new research institutes focused on artificial intelligence and quantum information sciences.

The effort is designed to ensure the U.S. remains globally competitive in AI and quantum technologies, administration officials said.

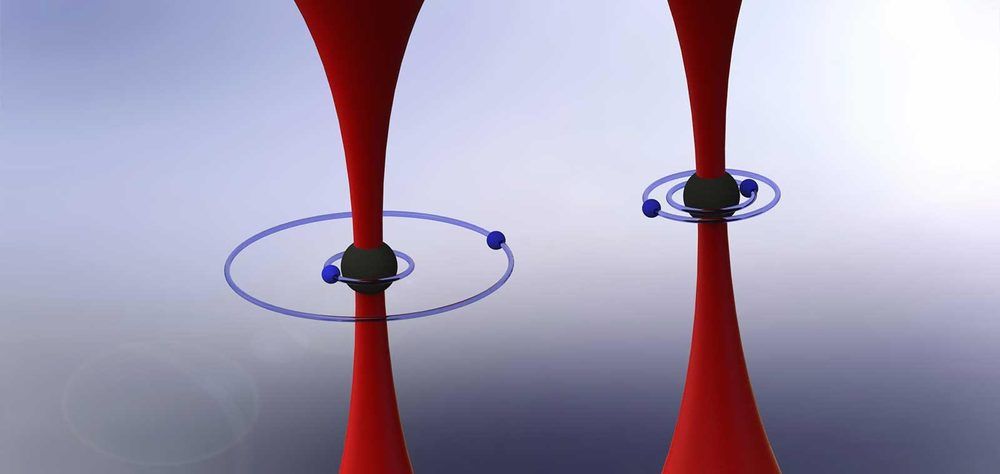

Physicists’ latest achievement with neutral atoms paves the way for new quantum computer designs.

In the quest to develop quantum computers, physicists have taken several different paths. For instance, Google recently reported that their prototype quantum computer might have made a specific calculation faster than a classical computer. Those efforts relied on a strategy that involves superconducting materials, which are materials that, when chilled to ultracold temperatures, conduct electricity with zero resistance. Other quantum computing strategies involve arrays of charged or neutral atoms.

Now, a team of quantum physicists at Caltech has made strides in work that uses a more complex class of neutral atoms called the alkaline-earth atoms, which reside in the second column of the periodic table. These atoms, which include magnesium, calcium, and strontium, have two electrons in their outer regions, or shells. Previously, researchers who experimented with neutral atoms had focused on elements located in the first column of the periodic table, which have just one electron in their outer shells.