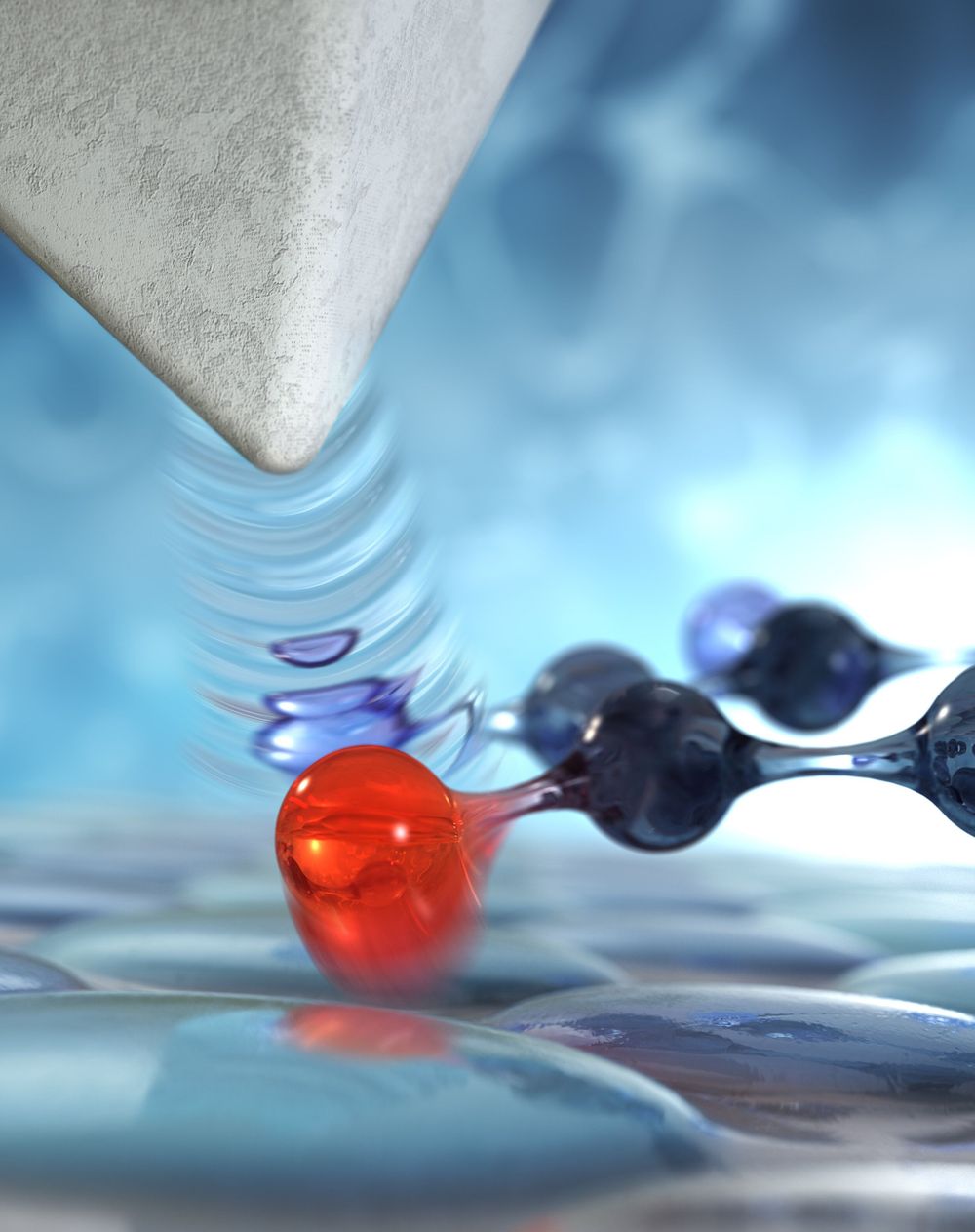

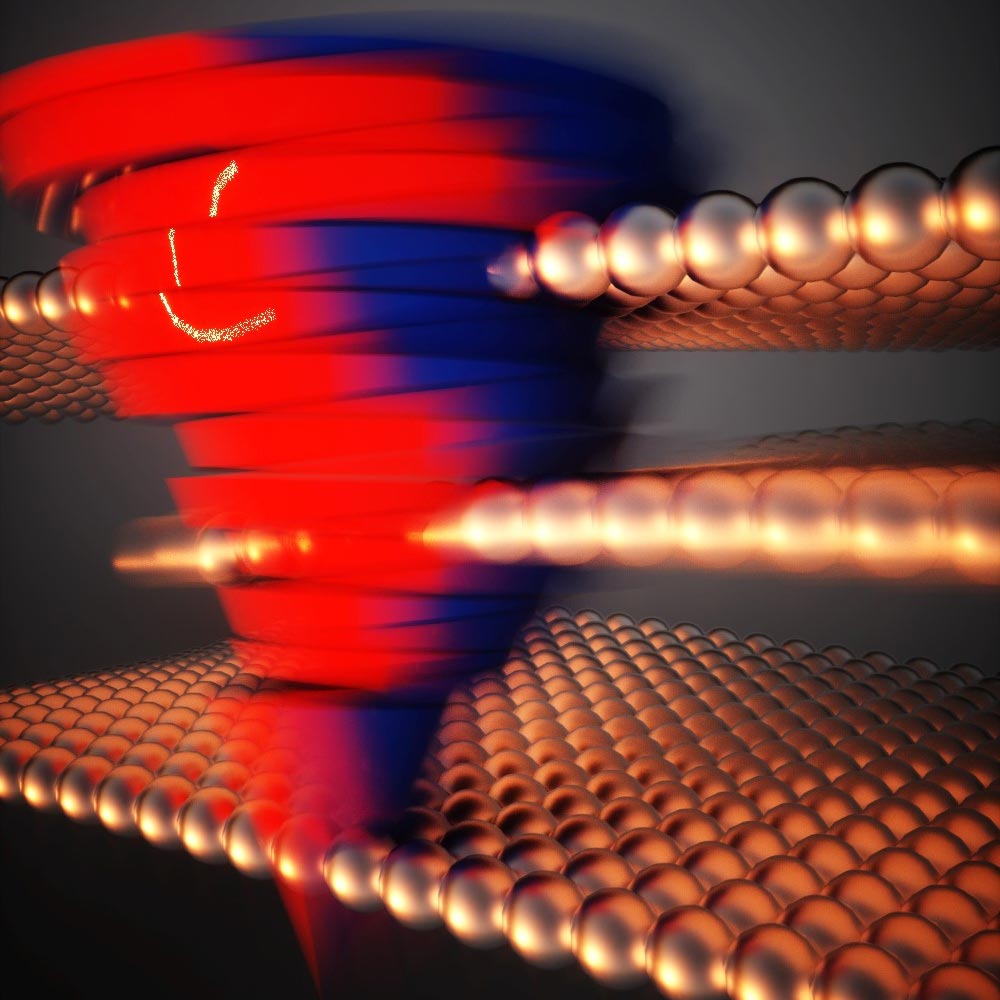

Scientists from Regensburg and Zurich have found a fascinating way to push an atom with controlled forces so quickly that they can choreograph the motion of a single molecule within less than a trillionth of a second. The extremely sharp needle of their unique ultrafast microscope serves as the technical basis: It carefully scans molecules, similar to a record player. Physicists at the University of Regensburg now showed that shining light pulses onto this needle can transform it into an ultrafast “atomic hand.” This allows molecules to be steered—and new technologies can be inspired.

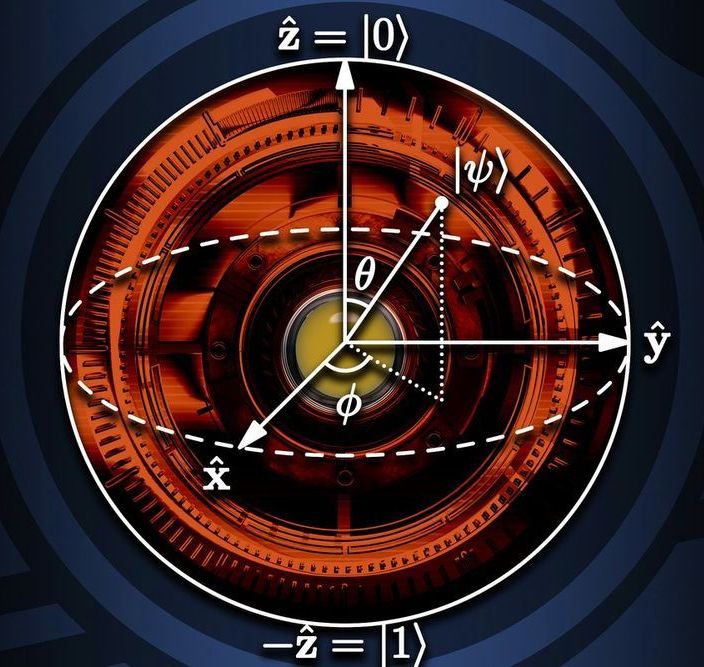

Atoms and molecules are the constituents of virtually all matter that surrounds us. Interacting with each other according to the rules of quantum mechanics, they form complex systems with an infinite variety of functions. To examine chemical reactions, biological processes in a cell, or new ways of solar energy harvesting, scientists would love to not only observe individual molecules, but even control them.

Most intuitively, people learn by haptic exploration, such as pushing, pulling, or tapping. Naturally, we are used to macroscopic objects that we can directly touch, squeeze or nudge by exerting forces. Similarly, atoms and molecules interact via forces, but these forces are extreme in multiple respects. First, the forces acting between atoms and molecules occur at extremely small lengths. In fact, these objects are so small that a special length scale has been introduced to measure them: 1 Ångström (1Å = 0.000,000,000,1 m). Second, at the same time, atoms and molecules move and wiggle around extremely fast. In fact, their motion takes place faster than picoseconds (1 ps = 0.000,000,000,001 s). Hence, to directly steer a molecule during its motion, a tool is required to generate ultrafast forces at the atomic scale.