Predicting an economic “singularity” approaching, Kevin Carson from the Center for a Stateless Society writes in The Homebrew Industrial Revolution (2010) we can look forward to a vibrant “alternative economy” driven less and less by corporate and state leviathans.

According to Carson, “the more technical advances lower the capital outlays and overhead for production in the informal economy, the more the economic calculus is shifted” (p. 357). While this sums up the message of the book and its relevance to advocates of open existing and emerging technologies, the analysis Carson offers to reach his conclusions is extensive and sophisticated.

With the technology of individual creativity expanding constantly, the analysis goes, “increasing competition, easy diffusion of new technology and technique, and increasing transparency of cost structure will – between them – arbitrage the rate of profit to virtually zero and squeeze artificial scarcity rents” (p. 346).

An unrivalled champion of arguments against “intellectual property”, the author believes IP to be nothing more than a last-ditch attempt by talentless corporations to continue making profit at the expensive of true creators and scientists (p. 114–129). The view has significant merit.

“The worst nightmare of the corporate dinosaurs”, Carson writes of old-fashioned mass-production-based and propertied industries, is that “the imagination might take a walk” (p. 311). Skilled creators could find the courage to declare independence from big brands. If not now, in the near future, technology will be advanced and available enough that the creators and scientists don’t need to work as helpers for super-rich corporate executives. Nor will the future see such men and women kept at dystopian, centralized factories.

Pointing to the crises of overproduction and waste, together with seemingly inevitable technological unemployment, Carson believes corporate capitalism is at death’s door. Due to “terminal crisis”, not only are other worlds possible but “this world, increasingly, is becoming impossible” (p. 82). Corporations, the author persuades us, only survive because they live off the subsidies of the government. But “as the system approaches its limits of sustainability”, “libertarian and decentralist technologies and organizational forms” are destined to “break out of their state capitalist integument and become the building blocks of a fundamentally different society” (p. 111–112).

Giant corporations are no longer some kind of necessary evil needed to ensure wide-scale manufacture and distribution of goods in our globalized world. Increasingly, they are only latching on to the talents of individuals to extract rents. They may even be neutering technological modernity and the raising of living standards, to extract as much profit as possible by allowing only slow improvements.

And why should corporations milk anyone, if those creators are equipped and talented enough to work for themselves?

The notion of creators declaring independence is not solely a question of things to come. While Kevin Carson links the works of Karl Hess, Jane Jacobs and others (p. 192–194) to imagine alternative friendly, localized community industries of a high-tech nature that will decrease the waste and dependency bred by highly centralized production and trade, he also points to recent technologies and their social impact.

“Computers have promised to be a decentralizing force on the same scale as electrical power a century earlier” (p. 197), the author asserts, referring to theories of the growth of electricity as a utility and its economic potential. From the subsequent growth of the internet, blogging is replacing centralized and costly news networks and publications to be the source of everyone’s information (p. 199). The decentralization brought by computers has meant “the minimum capital outlay for entering most of the entertainment and information industry has fallen to a few thousand dollars at most, and the marginal cost of reproduction is zero” (p. 199).

The vision made possible by books like Kevin Carson’s might be that one day, not only information products but physical products – everything – will be free. The phrase “knowledge is free”, a slogan of Anonymous hackers and their sympathizers, is true in two senses. Not only does “information want to be free”, the origin of the phrase explained by Wired co-founder Kevin Kelly in What Technology Wants (2010), but one can acquire knowledge at zero cost.

If the “transferrability” of individual creativity and peer production “to the realm of physical production” from the “immaterial realm” is a valid observation (p. 204–227), then the economic singularity means one thing clear. “Knowledge is free” shall become “everything is free”.

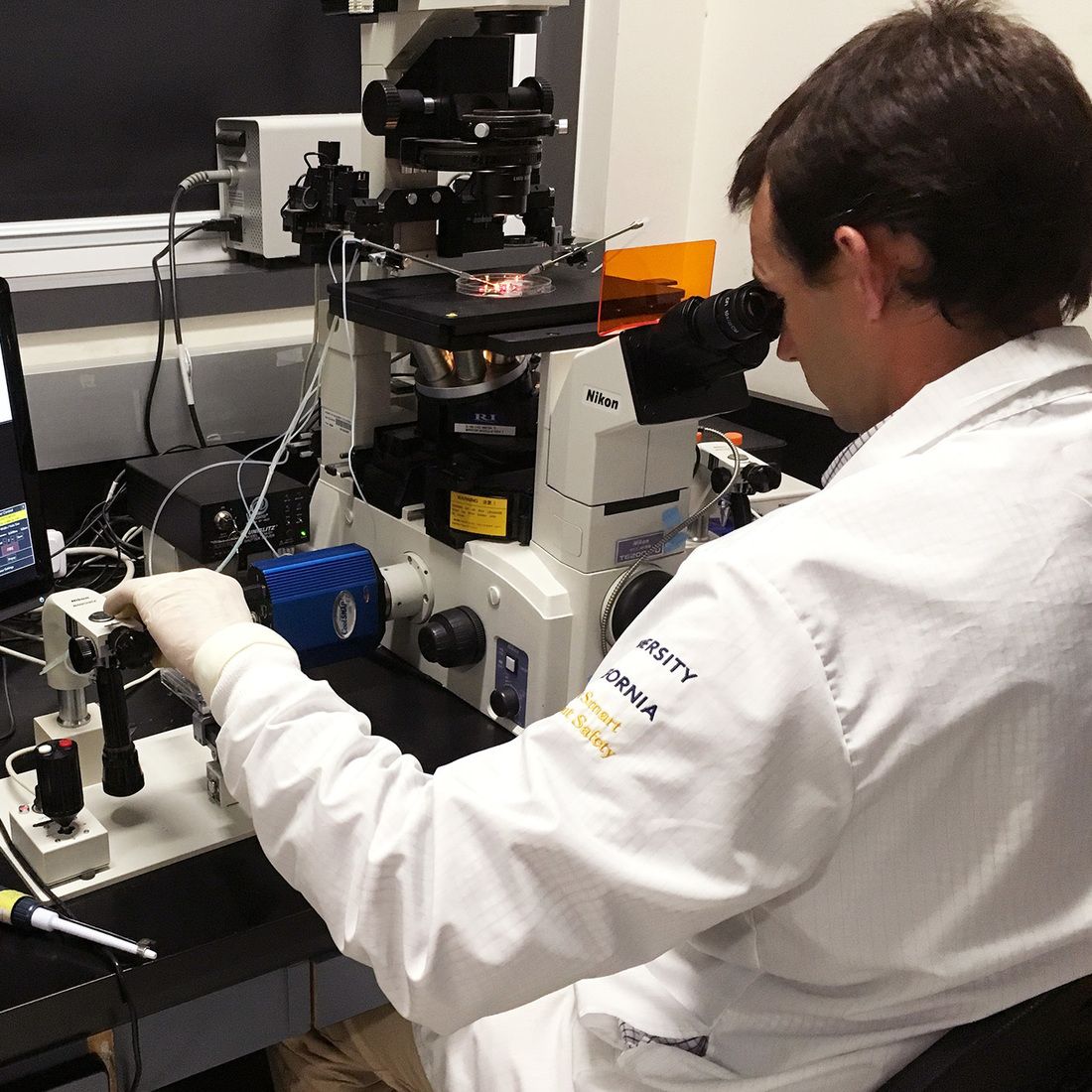

“Newly emerging forms of manufacturing”, the author indicated, “require far less capital to undertake production. The desktop revolution has reduced the capital outlays required for music, publishing and software by two orders of magnitude; and the newest open-source designs for computerized machine tools are being produced by hardware hackers for a few hundred dollars” (p. 84).

Open source hardware is of course also central to the advocacy in The Homebrew Industrial Revolution, especially as it relates to poorer peripheries of the world-economy. It is through open source hardware libraries of the kind advocated by Vinay Gupta that plans for alternative manufacture as the starting point in an alternative economy for the good of all become feasible.

As I argued in my 2013 Catalyst booklet, not only informational goods will face the scandals of being “leaked” or “pirated” in future. The right generation of 3D printers, robots, atomically-precise manufacturing devices, biotechnology-derived medicines and petrochemicals will all move “at the speed of light” as the father of synthetic biology J. Craig Venter predicted of his own synbio work.

[youtube_sc url=“https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hYWHJudLjq0”]

The fuel of an economic singularity, those above creations should be of primary interest in the formation of an alternative economy. They would not only have zero cost and zero waiting times, but they would require zero effort. Simply shared, they must be allowed to raise the living standards of humanity and allow poor countries to leapfrog several stages of development, breaking free of the bonds of exploitation.

One area to be criticized in the book could be a portion in which it reflects negatively on the very creation of railways or other state-imposed infrastructure and standards as a wrong turn in history, because these created an artificial niche for corporations to thrive (p. 5–23). It seems to undermine the book’s remaining thesis that the right turn in history consists of “libertarian and decentralist technologies and organizational forms”. “Network” technologies and organizational forms only exist due to that wave of prior mass production and imposed infrastructure the author claimed to be unnecessary. Without the satellites and thousands of kilometers of cable made in factories and installed by states, any type of “network” organizational form would be a weak proposition and the internet would never have existed.

Arguably, now the standards are set, future technological endeavors that connect and bridge society won’t need new standards imposed from above or vast physical infrastructure subsidized by states. The formation of effective networks itself now produces new mechanisms for devising and imposing standards, ensuring interconnectivity and high living standards should continue to flourish under the type of alternative economy advocated in Carson’s book.

Abolish artificial scarcity, intellectual property, mandatory high overhead and other measures used by states to enforce the privileges of monopoly capitalism, the author tells us (p. 168–170). This way, a more humane world-economy can be engineered, oriented to benefit people and local communities foremost. Everyone in the world may get to work fewer hours while enjoying an improved quality of life, and we can prevent a bleak future in which millions of people are sacrificed to technological unemployment on the altar of profit.