50 years ago Herman Khan coined the term in his book “On thermonuclear war”. His ideas are still important. Now we can read what he really said online. His main ideas are that DM is feasable, that it will cost around 10–100 billion USD, it will be much cheaper in the future and there are good rational reasons to built it as ultimate mean of defence, but better not to built it, because it will lead to DM-race between states with more and more dangerous and effective DM as outcome. And this race will not be stable, but provoking one side to strike first. This book and especially this chapter inspired “Dr. Strangelove” movie of Kubrick.

Herman Khan. On Doomsday machine.

Category: policy

Cyberspace command to engage in warfare

The link is:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/31511398/ns/us_news-military/

“The low-key launch of the new military unit reflects the Pentagon’s fear that the military might be seen as taking control over the nation’s computer networks.”

“Creation of the command, said Deputy Defense Secretary William Lynn at a recent meeting of cyber experts, ‘will not represent the militarization of cyberspace.’”

And where is our lifeboat?

The Lifeboat Conversation

Many years ago, in December 1993 to be approximate, I noticed a space-related poster on the wall of Eric Klien’s office in the headquarters of the Atlantis Project. We chatted for a bit about the possibilities for colonies in space. Later, Eric mentioned that this conversation was one of the formative moments in his conception of the Lifeboat Foundation.

Another friend, filmmaker Meg McLain has noticed that orbital hotels and space cruise liners are all vapor ware. Indeed, we’ve had few better depictions of realistic “how it would feel” space resorts since 1968’s Kubrick classic “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Remember the Pan Am flight to orbit, the huge hotel and mall complex, and the transfer to a lunar shuttle? To this day I know people who bought reservation certificates for whenever Pan Am would begin to fly to the Moon.

In 2004, after the X Prize victory, Richard Branson announced that Virgin Galactic would be flying tourists by 2007. So far, none.

A little later, Bigelow announced a fifty million dollar prize if only tourists could be launched to orbit by January 2010. I expect the prize money won’t be claimed in time.

Why? Could it be that the government is standing in the way? And if tourism in space can’t be “permitted” what of a lifeboat colony?

Meg has set out to make a documentary film about how the human race has arrived four decades after the Moon landing and still no tourist stuff. Two decades after Kitty Hawk, a person could fly across the country; three decades, across any ocean.

Where are the missing resorts?

Here is the link to her film project:

http://www.freewebs.com/11at40/

On Being Bitten to Death by Ducks

(Crossposted on the blog of Starship Reckless)

Working feverishly on the bench, I’ve had little time to closely track the ongoing spat between Dawkins and Nisbet. Others have dissected this conflict and its ramifications in great detail. What I want to discuss is whether scientists can or should represent their fields to non-scientists.

There is more than a dollop of truth in the Hollywood cliché of the tongue-tied scientist. Nevertheless, scientists can explain at least their own domain of expertise just fine, even become major popular voices (Sagan, Hawkin, Gould — and, yes, Dawkins; all white Anglo men, granted, but at least it means they have fewer gatekeepers questioning their legitimacy). Most scientists don’t speak up because they’re clocking infernally long hours doing first-hand science and/or training successors, rather than trying to become middle(wo)men for their disciplines.

Experimental biologists, in particular, are faced with unique challenges: not only are they hobbled by ever-decreasing funds for basic research while expected to still deliver like before. They are also beset by anti-evolutionists, the last niche that science deniers can occupy without being classed with geocentrists, flat-earthers and exorcists. Additionally, they are faced with the complexity (both intrinsic and social) of the phenomenon they’re trying to understand, whose subtleties preclude catchy soundbites and get-famous-quick schemes.

Last but not least, biologists have to contend with self-anointed experts, from physicists to science fiction writers to software engineers to MBAs, who believe they know more about the field than its practitioners. As a result, they have largely left the public face of their science to others, in part because its benefits — the quadrupling of the human lifespan from antibiotics and vaccines, to give just one example — are so obvious as to make advertisement seem embarrassing overkill.

As a working biologist, who must constantly “prove” the value of my work to credentialed peers as well as laypeople in order to keep doing basic research on dementia, I’m sick of accommodationists and appeasers. Gould, despite his erudition and eloquence, did a huge amount of damage when he proposed his non-overlapping magisteria. I’m tired of self-anointed flatulists — pardon me, futurists — who waft forth on biological topics they know little about, claiming that smatterings gleaned largely from the Internet make them understand the big picture (much sexier than those plodding, narrow-minded, boring experts!). I’m sick and tired of being told that I should leave the defense and promulgation of scientific values to “communications experts” who use the platform for their own aggrandizement.

Nor are non-scientists served well by condescending pseudo-interpretations that treat them like ignorant, stupid children. People need to view the issues in all their complexity, because complex problems require nuanced solutions, long-term effort and incorporation of new knowlege. Considering that the outcomes of such discussions have concrete repercussions on the long-term viability prospects of our species and our planet, I staunchly believe that accommodationism and silence on the part of scientists is little short of immoral.

Unlike astronomy and physics, biology has been reluctant to present simplified versions of itself. Although ours is a relatively young science whose predictions are less derived from general principles, our direct and indirect impact exceeds that of all others. Therefore, we must have articulate spokespeople, rather than delegate discussion of our work to journalists or politicians, even if they’re well-intentioned and well-informed.

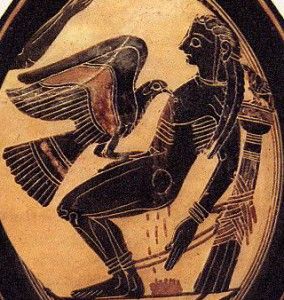

Image: Prometheus, black-figure Spartan vase ~500 BCE.

How long do we have? — Regulate armed robots before it’s too late

NewScientist — March 10, 2009, by A. C. Grayling

IN THIS age of super-rapid technological advance, we do well to obey the Boy Scout injunction: “Be prepared”. That requires nimbleness of mind, given that the ever accelerating power of computers is being applied across such a wide range of applications, making it hard to keep track of everything that is happening. The danger is that we only wake up to the need for forethought when in the midst of a storm created by innovations that have already overtaken us.

We are on the brink, and perhaps to some degree already over the edge, in one hugely important area: robotics. Robot sentries patrol the borders of South Korea and Israel. Remote-controlled aircraft mount missile attacks on enemy positions. Other military robots are already in service, and not just for defusing bombs or detecting landmines: a coming generation of autonomous combat robots capable of deep penetration into enemy territory raises questions about whether they will be able to discriminate between soldiers and innocent civilians. Police forces are looking to acquire miniature Taser-firing robot helicopters. In South Korea and Japan the development of robots for feeding and bathing the elderly and children is already advanced. Even in a robot-backward country like the UK, some vacuum cleaners sense their autonomous way around furniture. A driverless car has already negotiated its way through Los Angeles traffic.

In the next decades, completely autonomous robots might be involved in many military, policing, transport and even caring roles. What if they malfunction? What if a programming glitch makes them kill, electrocute, demolish, drown and explode, or fail at the crucial moment? Whose insurance will pay for damage to furniture, other traffic or the baby, when things go wrong? The software company, the manufacturer, the owner?

Most thinking about the implications of robotics tends to take sci-fi forms: robots enslave humankind, or beautifully sculpted humanoid machines have sex with their owners and then post-coitally tidy the room and make coffee. But the real concern lies in the areas to which the money already flows: the military and the police.

A confused controversy arose in early 2008 over the deployment in Iraq of three SWORDS armed robotic vehicles carrying M249 machine guns. The manufacturer of these vehicles said the robots were never used in combat and that they were involved in no “uncommanded or unexpected movements”. Rumours nevertheless abounded about the reason why funding for the SWORDS programme abruptly stopped. This case prompts one to prick up one’s ears.

Media stories about Predator drones mounting missile attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan are now commonplace, and there are at least another dozen military robot projects in development. What are the rules governing their deployment? How reliable are they? One sees their advantages: they keep friendly troops out of harm’s way, and can often fight more effectively than human combatants. But what are the limits, especially when these machines become autonomous?

The civil liberties implications of robot devices capable of surveillance involving listening and photographing, conducting searches, entering premises through chimneys or pipes, and overpowering suspects are obvious. Such devices are already on the way. Even more frighteningly obvious is the threat posed by military or police-type robots in the hands of criminals and terrorists.

There needs to be a considered debate about the rules and requirements governing all forms of robot devices, not a panic reaction when matters have gone too far. That is how bad law is made — and on this issue time is running out.

A. C. Grayling is a philosopher at Birkbeck, University of London

The Disclosure Project May 9th 2001 National Press Club Conference and DEAFENING SILENCE: Media Response to the May 9th Event and its Implications Regarding the Truth of Disclosure by Jonathan Kolber

DEAFENING SILENCE: Media Response to the May 9th Event

and its Implications Regarding the Truth of Disclosure

by Jonathan Kolber

http://www.disclosureproject.org/May9response.htm

My intent is to establish that the media’s curiously limited coverage of the May 9, 2001 National Press Club briefing is highly significant.

At that event, nearly two dozen witnesses stepped forward and offered their testimony as to personal knowledge of ET’s and ET-related technologies. These witnesses claimed top secret clearances and military and civilian accomplishments of the highest order. Some brandished uncensored secret documents. The world’s major media were in attendance, yet few reported what they saw, most neglecting to even make skeptical mention.

How can this be? Major legal trials are decided based on weaker testimony than was provided that day. Prison sentences are meted out on less. The initial Watergate evidence was less, and the implications of this make Watergate insignificant by comparison. Yet the silence is deafening.

Three Possibilities:

If true, the witness testimony literally ushers in the basis for a whole new world of peace and prosperity for all. Validating the truth of Disclosure is probably the most pressing question of our times. The implications for the human future are so overwhelming that virtually everything else becomes secondary. However, the mass media have not performed validation. No investigative stories seeking to prove or disprove the witness testimony have appeared.

This cannot be due to lack of material; in the remainder of this article I will perform validation based upon material handed to the world’s media on May 9th.

In my view, only three possibilities exist: the witnesses were all lying, they were all delusional, or they were documenting the greatest cover-up in history. The reason is that if any one witness were neither lying nor delusional, then the truth of Disclosure is established. Let’s examine each possibility in turn.

If the witnesses were lying, a reasonable observer would ask, “where is the payoff?” What is the possible benefit to a liar pleading for the chance to testify before Congress under oath? The most likely payoff would be a trip to jail. These witnesses have not openly requested any financial compensation, speaking engagements or the like, and the Disclosure Project’s operation cannot support a payoff to dozens of persons. A cursory evaluation of its “products” coupled with a visit to its Charlottesville offices will establish this. Further, the parent organization, CSETI, is an IRS 501C3 nonprofit organization, and its lack of financial resources is a matter of public record. So the notion that the witnesses were doing so for material benefit is unsupported by facts at hand.

To my knowledge, large numbers of persons do not collude to lie without some compelling expected benefit. Other than money, the only such reason I can conceive in this case would be ideology. I wonder what radical extremist “ideology” could plausibly unite such a diverse group of senior corporate and military witnesses, nearly all of whom have previously displayed consistent loyalty to the United States in word and deed? I find none, and I therefore dismiss lying as implausible.

Further, the witnesses claimed impressive credentials. Among them were a Brigadier General, an Admiral, men who previously had their finger on the nuclear launch trigger, air traffic controllers, Vice Presidents of major American corporations—persons who either routinely have had our lives in their hands or made decisions affecting everyone. To my knowledge, in the half-year since May 9th, not a single claimed credential has been challenged in a public forum. Were they lying en masse, such an exposure would be a nice feather in the cap of some reporter. However, it hasn’t happened.

If all the witnesses were delusional, then a reasonable observer would presume that such “mass psychosis” did not suddenly manifest. That is, a number of witnesses would have shown psychotic tendencies in the past, in some cases probably including hospitalization. To my knowledge, this has not been alleged.

If they were documenting the greatest cover-up in history, and especially as briefing books that enumerated details of specific cases were handed out on May 9th to the dozens of reporters present, coverage should have dominated the media ever since, with a national outcry for hearings. This did not happen either.

Implications:

What do the above facts and inferences imply about the state of affairs in the media and the credibility of the witness testimony? In my view, they imply a lot.

If the witnesses were neither lying nor delusional, then the deafening media silence following May 9th implies an intentional process of failure to explore and reveal the truth. Said less politely, it implies censorship. (If I am right, this is itself an explosive statement, worthy of significant media attention—which it will not receive.) The only stories comparable in significance to May 9th would be World War III, a plague decimating millions, or the like. Yet between May 9th and September 11th, the news media was saturated with stories that are comparatively trivial.

Briefing documents were provided to reporters present. These books provided much of due diligence necessary for those reporters to explore the truth. However, neither Watergate-type coverage nor exposure of witness fraud has followed.

One of the witnesses reported how he became aware of 43 persons on the payrolls of major media organs while in fact working for the US government. Their job was to intercept ET-related stories and squelch, spin or ridicule. If we accept his testimony as factual, it provides a plausible explanation for the deafening silence following May 9th.

There is a bright spot in this situation. Some of the media did provide coverage, if only for a few days. This suggests that those who control media reporting do not have a monolithic power; they can be circumvented. The event did run on the internet and was seen by 250,000 viewers, despite “sophisticated electronic jamming” during the first hour (words attributed to the broadcast provider, not the Disclosure Project). Indeed, it continues to be fully documented at the Project’s web site.

Conclusions:

Since an expose of witness deceit or mass psychosis would itself have been a good, career-building story for some reporter, but no such story has appeared, I conclude that these witnesses are who they claim to be.

If these witnesses are who they claim to be, then they presented testimony they believe truthful. Yet no factual detail of any of that testimony has since been disputed in the media. Half a year is enough time to do the research. I believe the testimony is true as presented.

If the data is true as presented and the media are essentially ignoring what is indisputably the greatest story of our era, then the media are not performing the job they claim to do. Either they are being suppressed/censored, or they do not believe the public would find this subject interesting.

The tabloids continuously run stories on ET-related subjects, and polls show high public interest in the subject, so lack of interest value cannot be the explanation. I conclude that there is active suppression. This is corroborated by the witness claim of 43 intelligence operatives on major media payrolls.

Despite active suppression, enough coverage of the May 9th event happened in major publications and broadcast media to prove that the suppression can be thwarted. An event of significant enough impact and orchestration can break through the censorship. Millions of persons previously unaware of or dubious about ET-related technologies and their significance for ending our dependence on Arab oil have since become aware.

We live in a controlled society, one in which the control is secretive yet masquerades as openness. Yet, as proven May 9th, this control can be overcome by the concerted efforts of determined groups of persons. We must seek such opportunities again.

Russian Lifeboat Foundation NanoShield

I have translated into Russian “Lifeboat Foundation Nanoshield” http://www.scribd.com/doc/12113758/Nano-Shield and I have some thoughts about it:

1) The effective mean of defense against ecofagy would be to turn in advance all the matter on the Earth into nanorobots. Just as every human body is composed of living cells (although this does not preclude the emergence of cancer cells). The visible world would not change. All object will consist of nano-cells, which would have sufficient immune potential to resist almost any foreseeable ecofagy. (Except purely informational like computer viruses). Even in each leaving cell would be small nanobot, which would control it. Maybe the world already consists of nanobots.

2) The authors of the project suggest that ecofagic attack would consist of two phases — reproduction and destruction. However, creators of ecofagy, could make three phases — first phase would be a quiet distribution throughout the Earth’s surface, under surfase, in the water and air. In this phase nanorobots will multiply in slow rate, and most importantly, sought to be removed from each other on the maximum distance. In this case, their concentration everywhere on the Earth as a result would be 1 unit on the cube meter (which makes them unrecognazible). And only after it they would start to proliferate intensely, simultaneously creating nanorobots soldiers who did not replicate, but attack the defensive system. In doing so, they first have to suppress protection systems, like AIDS. Or as a modern computer viruses switches off the antivirus. Creators of the future ecofagy must understand it. As the second phase of rapid growth begins everywhere on the surface of the Earth, then it would be impossible to apply the tools of destruction such as nuclear strikes or aimed rays, as this would mean the death of the planet in any case — and simply would not be in store enough bombs.

3) The authors overestimate the reliability of protection systems. Any system has a control center, which is a blank spot. The authors implicitly assume that any person with a certain probability can suddenly become terrorist willing to destroy the world (and although the probability is very small, a large number of people living on Earth make it meaningful). But because such a system will be managed by people, they may also want to destroy the world. Nanoshield could destroy the entire world after one erroneous command. (Even if the AI manages it, we cannot say a priori that the AI cannot go mad.) The authors believe that multiple overlapping of Nanoshield protection from hackers will make it 100 % safe, but no known computer system is 100 % safe – but all major computer programs were broken by hackers, including Windows and IPod.

4) Nanoshield could develop something like autoimmunity reaction. The author’s idea that it is possible to achieve 100 % reliability by increasing the number of control systems is very superficial, as well as the more complex is the system, the more difficult is to calculate all the variants of its behavior, and the more likely it will fail in the spirit of the chaos theory.

5) Each cubic meter of oceanic water contains 77 million living beings (on the northern Atlantic, as the book «Zoology of Invertebrates» tells). Hostile ecofages can easily camouflage under natural living beings, and vice versa; the ability of natural living beings to reproduce, move and emit heat will significantly hamper detection of ecofages, creating high level of false alarms. Moreover, ecofages may at some stage in their development be fully biological creatures, where all blueprints of nanorobot will be recorded in DNA, and thus be almost no distinguishable from the normal cell.

6) There are significant differences between ecofages and computer viruses. The latter exist in the artificial environment that is relatively easy to control — for example, turn off the power, get random access to memory, boot from other media, antivirus could be instantaneous delivered to any computer. Nevertheless, a significant portion of computers were infected with a virus, but many users are resigned to the presence of a number of malware on their machines, if it does not slow down much their work.

7) Compare: Stanislaw Lem wrote a story “Darkness and mold” with main plot about ecofages.

8 ) The problem of Nanoshield must be analyzed dynamically in time — namely, the technical perfection of Nanoshield should precede technical perfection of nanoreplikators in any given moment. From this perspective, the whole concept seems very vulnerable, because to create an effective global Nanoshield require many years of development of nanotechnology — the development of constructive, and political development — while creating primitive ecofages capable, however, completely destroy the biosphere, is required much less effort. Example: Creating global missile defense system (ABM – still not exist) is much more complex technologically and politically, than the creation of intercontinental nuclear missiles.

9) You should be aware that in the future will not be the principal difference between computer viruses and biological viruses and nanorobots — all them are information, in case of availability of any «fabs» which can transfer information from one carrier to another. Living cells could construct nanorobots, and vice versa; spreading over computer networks, computer viruses can capture bioprinters or nanofabs and force them to perform dangerous bioorganizms or nanorobots (or even malware could be integrated into existing computer programs, nanorobots or DNA of artificial organisms). These nanorobots can then connect to computer networks (including the network which control Nanoshield) and send their code in electronic form. In addition to these three forms of the virus: nanotechnology, biotechnology and computer, are possible other forms, for example, cogno — that is transforming the virus in some set of ideas in the human brain which push the man to re-write computer viruses and nanobots. Idea of “hacking” is now such a meme.

10) It must be noted that in the future artificial intelligence will be much more accessible, and thus the viruses would be much more intelligent than today’s computer viruses, also applies to nanorobots: they will have a certain understanding of reality, and the ability to quickly rebuild itself, even to invent its innovative design and adapt to new environments. Essential question of ecofagy is whether individual nanorobots are independent of each other, as the bacteria cells, or they will act as a unified army with a single command and communication systems. In the latter case, it is possible to intercept the management of hostile army ecofages.

11) All that is suitable to combat ecofagy, is suitable as a defensive (and possibly offensive) weapons in nanowar.

12) Nanoshield is possible only as global organization. If there is part of the Earth which is not covered by it, Nanoshield will be useless (because there nanorobots will multiply in such quantities that it would be impossible to confront them). It is an effective weapon against people and organizations. So, it should occur only after full and final political unification of the globe. The latter may result from either World War for the unification of the planet, either by merging of humanity in the face of terrible catastrophes, such as flash of ecofagy. In any case, the appearance of Nanoshield must be preceded by some accident, which means a great chance of loss of humanity.

13) Discovery of «cold fusion» or other non-conventional energy sources will make possible much more rapid spread of ecofagy, as they will be able to live in the bowels of the earth and would not require solar energy.

14) It is wrong to consider separately self-replicating and non-replitcating nanoweapons. Some kinds of ecofagy can produce nano-soldiers attacking and killing all life. (This ecofagy can become a global tool of blackmail.) It has been said that to destroy all people on the Earth can be enough a few kilograms of nano-soldiers. Some kinds of ecofagy in early phase could dispersed throughout the world, very slowly and quietly multiply and move, and then produce a number of nano-soldiers and attack humans and defensive systems, and then begin to multiply intensively in all areas of the globe. But man, stuffed with nano-medicine, can resist attack of nanosoldier as well as medical nanorobots will be able to neutralize any poisons and tears arteries. In this small nanorobot must attack primarily informational, rather than from a large selection of energy.

15) Did the information transparency mean that everyone can access code of dangerous computer virus, or description of nanorobot-ecofage? A world where viruses and knowledge of mass destruction could be instantly disseminated through the tools of information transparency is hardly possible to be secure. We need to control not only nanorobots, but primarily persons or other entities which may run ecofagy. The smaller is the number of these people (for example, scientists-nanotechnologist), the easier would be to control them. On the contrary, the diffusion of knowledge among billions of people will make inevitable emergence of nano-hackers.

16) The allegation that the number of creators of defense against ecofagy will exceed the number of creators of ecofagy in many orders of magnitude, seems doubtful, if we consider an example of computer viruses. Here we see that, conversely, the number of virus writers in the many orders of magnitude exceeds the number of firms and projects on anti-virus protection, and moreover, the majority of anti-virus systems cannot work together as they stops each other. Terrorists may be masked by people opposing ecofagy and try to deploy their own system for combat ecofagy, which will contain a tab that allows it to suddenly be reprogrammed for the hostile goal.

17) The text implicitly suggests that Nanoshield precedes to the invention of self improving AI of superhuman level. However, from other prognosis we know that this event is very likely, and most likely to occur simultaneously with the flourishing of advanced nanotechnology. Thus, it is not clear in what timeframe the project Nanoshield exist. The developed artificial intelligence will be able to create a better Nanoshield and Infoshield, and means to overcome any human shields.

18) We should be aware of equivalence of nanorobots and nanofabrics — first can create second, and vice versa. This erases the border between the replicating and non-replicating nanomachines, because a device not initially intended to replicate itself can construct somehow nanorobot or to reprogram itself into capable for replication nanorobot.

Nanotech Development: You Can’t Please All of the People, All of the Time

Abstract

What counts as rational development and commercialization of a new technology—especially something as potentially wonderful (and dangerous) as nanotechnology? A recent newsletter of the EU nanomaterials characterization group NanoCharM got me thinking about this question. Several authors in this newsletter advocated, by a variety of expressions, a rational course of action. And I’ve heard similar rhetoric from other camps in the several nanoscience and nanoengineering fields.

We need a sound way of characterizing nanomaterials, and then an account of their fate and transport, and their novel properties. We need to understand the bioactivity of nanoparticles, and their effect in the environments where they may end up. We need to know what kinds of nanoparticles occur naturally, which are incidental to other engineering processes, and which we can engineer de novo to solve the world’s problems—and to fill some portion of the world’s bank accounts. We need life-cycle analyses, and toxicity and exposure studies, and cost-benefit analyses. It’s just the rational way to proceed. Well who could argue with that?

Article

What counts as rational development and commercialization of a new technology—especially something as potentially wonderful (and dangerous) as nanotechnology? A recent newsletter of the EU nanomaterials characterization group NanoCharM got me thinking about this question. Several authors in this newsletter advocated, by a variety of expressions, a rational course of action. And I’ve heard similar rhetoric from other camps in the several nanoscience and nanoengineering fields.

We need a sound way of characterizing nanomaterials, and then an account of their fate and transport, and their novel properties. We need to understand the bioactivity of nanoparticles, and their effect in the environments where they may end up. We need to know what kinds of nanoparticles occur naturally, which are incidental to other engineering processes, and which we can engineer de novo to solve the world’s problems—and to fill some portion of the world’s bank accounts. We need life-cycle analyses, and toxicity and exposure studies, and cost-benefit analyses. It’s just the rational way to proceed. Well who could argue with that?

Leaving aside the lunatic fringe—those who would charge ahead guns (or labs) a-blazing—I suspect that there is broad but shallow agreement on and advocacy of the rational development of nanotechnology. That is, what is “rational” to the scientists might not be “rational” to many commercially oriented engineers, but each group would lay claim to the “rational” high ground. Neither conception of rational action is likely to be assimilated easily to the one shared by many philosophers and ethicists who, like me, have become fascinated by ethical issues in nanotechnology. And when it comes to rationality, philosophers do like to take the high ground but don’t always agree where it is to be found—except under one’s own feet. Standing on the top of the Himalayan giant K2, one may barely glimpse the top of Everest.

So in the spirit of semantic housekeeping, I’d like to introduce some slightly less abstract categories, to climb down from the heights of rationality and see if we might better agree (and more perspicuously disagree) on what to think and what to do about nanotechnology. At the risk of clumping together some altogether disparate researchers, I will posit that the three fields mentioned above—science, engineering, and philosophy—want different things from their “rational” courses of action.

The scientists, especially the academics, want knowledge of fundamental structures and processes of nanoparticles. They want to fit this knowledge into existing accounts of larger-scale particles in physics, chemistry, and biology. Or they want to understand how engineered and natural nanoparticles challenge those accounts. They want to understand why these particles have the causal properties that they do. Prudent action, from the scientific point of view, requires that we not change the received body of knowledge called science until we know what we’re talking about.

The engineers (with apologies here to academic engineers who are more interested in knowledge-creation than product-creation) want to make things and solve problems. Prudence on their view involves primarily ends-means or instrumental rationality. To pursue the wrong means to an end—for instance, to try to construct a new macro-level material from a supposed stock of a particular engineered nanoparticle, without a characterization or verification of what counts as one of those particles—is just wasted effort. For the engineers, wasted effort is a bad thing, since there are problems that want solutions, and solutions (especially to public health and environmental problems) are time sensitive. Some of these problems have solutions that are non-nanotech, and the market rewards the first through the gate. But the engineers don’t need a complete scientific understanding of nanoparticles to forge ahead with efforts. As Henry Petroski recently said in the Washington Post (1/25/09), “[s]cience seeks to understand the world as it is; only engineering can change it.”

The philosophers are of course a more troublesome lot. Prudence on their view takes on a distinctly moral tinge, but they recognize the other forms too. Philosophers are mostly concerned with the goodness of the ends pursued by the engineers, and the power of the knowledge pursued by the scientists. Ever since von Neumann’s suggestion of the technological inevitability of scientific knowledge, some philosophers have worried that today’s knowledge, set aside perhaps because of excessive risks, can become tomorrow’s disastrous products.

The key disagreement, though, is between the engineers and the philosophers, and the central issues concern the plurality of good ends, and the incompatibility of some of them with others. For example, it is certainly a good end to have clean drinking water worldwide today, and we might move towards that end by producing filtration systems with nanoscale silver or some other product. It is also a good end to have healthy aquatic ecosystems today, and to have viable fisheries tomorrow, and future people to benefit from them. These ends may not all be compatible. When we add up the good ends over many scales, the balancing problem becomes almost insurmountable. Just consider a quick accounting: today’s poor, many of whom will die from water-born disease; cancer patients sickened by the imprecise “cures” given to them, future people whose access to clean water and sustainable forms of energy hang in the balance. We could go on.

When we think about these three fields and their allegedly separate conceptions of prudent action, it becomes clear that their conceptions of prudence can be held by one and the same person, without fear of multiple personality disorder. Better, then, to consider these scientific, engineering, and philosophical mindsets, which are held in greater or lesser concentrations by many researchers. That they are held in different concentrations by the collective consciousness of the nanotechnology field is manifest, it seems, by the disagreement over the right principle of action to follow.

I don’t want to “psychologize” or explain away the debate over principles here, but isn’t it plausible to think that advocates of the Precautionary Principle have the philosophical mindset to a great degree, and so they believe that catastrophic harm to future generations isn’t worth even a very small risk? That is because they count the good ends to be lost as greater in number (and perhaps in goodness) than the good ends to be gained.

Those of the engineering mindset, on the other hand, want to solve problems for people living now, and they might not worry so much about future problems and future populations. They are apt to prefer a straightforward Cost-Benefit Principle, with serious discounting of future costs. The future, after all, will have their own engineers, and a new set of tools for the problems they face. Of course, those of us alive today will in large part create the problems faced by those future people. But we will also bequeath to them our science and engineering.

I’d like to offer a conjecture at this point about the basic insolubility of tensions between the scientific, engineering, and philosophical mindsets and their conceptions of prudent action. The conjecture is inspired by the Impossibility Theorem of the Nobel Prize winning economist Kenneth Arrow, but only informally resembles his brilliant conclusion. In a nutshell, it is this. If we believe that the nanotechnology field has to aggregate preferences for prudential action over these three mindsets, where there are multiple choices to be made over development and commercialization of nanotechnology’s products, we will not come to agreement on what counts as prudent action. This conjecture owes as much to the incommensurability of various good ends, and the means to achieve them, as it does to the kind of voting paradox of which Arrow’s is just one example.

If I am right in this conjecture, we shouldn’t be compelled to try to please all of the people all of the time. Once we give up on this “everyone wins” mentality, perhaps we can get on with the business of making difficult choices that will create different winners and losers, both now and in the future. Perhaps we will also get on with the very difficult task of achieving a comprehensive understanding of the goals of science, engineering, and ethics.

Thomas M. Powers, PhD

Director—Science, Ethics, and Public Policy Program

and

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

University of Delaware