Adding energy to any material, such as by heating it, almost always makes its structure less orderly. Ice, for example, with its crystalline structure, melts to become liquid water, with no order at all.

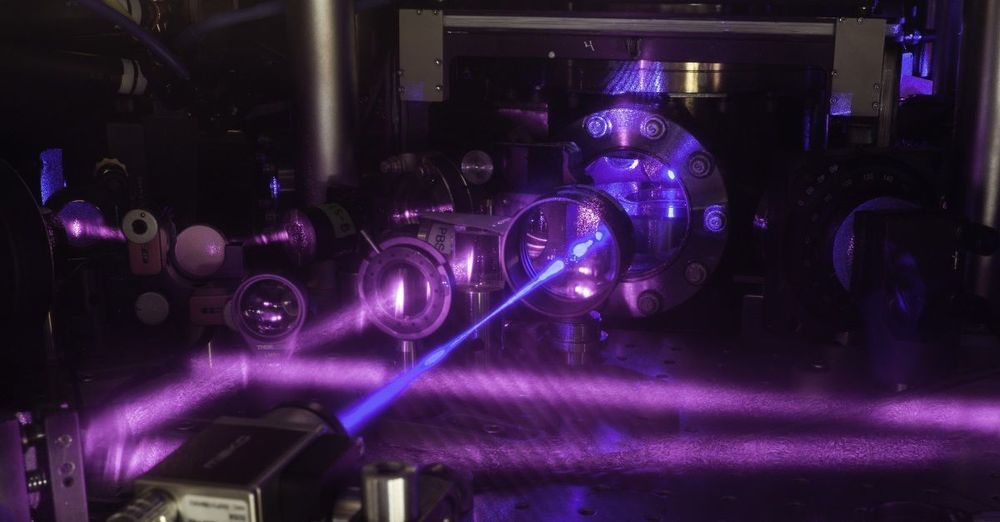

But in new experiments by physicists at MIT and elsewhere, the opposite happens: When a pattern called a charge density wave in a certain material is hit with a fast laser pulse, a whole new charge density wave is created—a highly ordered state, instead of the expected disorder. The surprising finding could help to reveal unseen properties in materials of all kinds.

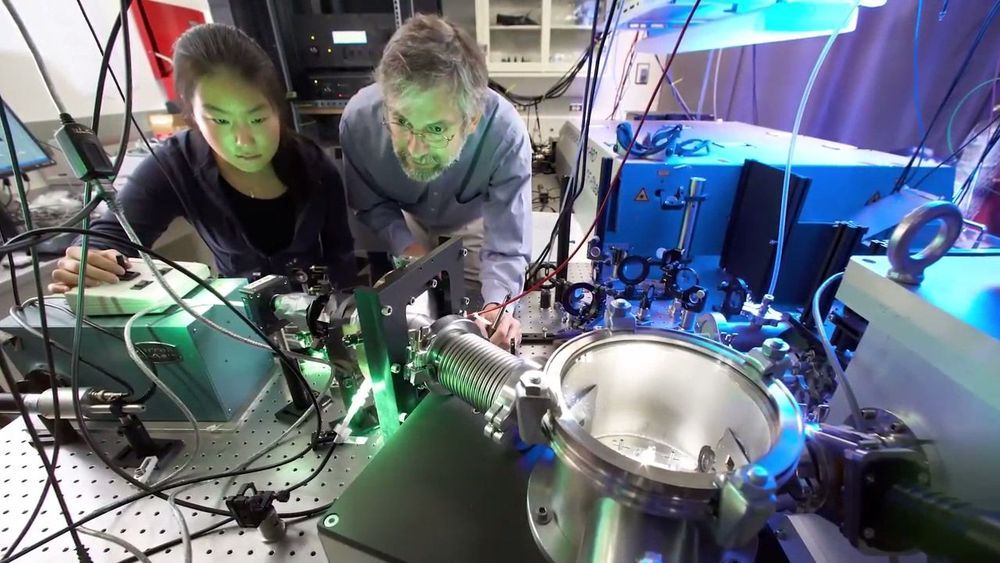

The discovery is being reported today in the journal Nature Physics, in a paper by MIT professors Nuh Gedik and Pablo Jarillo-Herrero, postdoc Anshul Kogar, graduate student Alfred Zong, and 17 others at MIT, Harvard University, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, and Argonne National Laboratory.