We are NOT our age we are our ENERGY

TIME is not real – it is a human construct to help us differentiate between now and our perception of the past, an equally astonishing and baffling theory states.

AMD has published its new FEMFX deformable materials physics library and made it available for anyone to use in games and other software development.

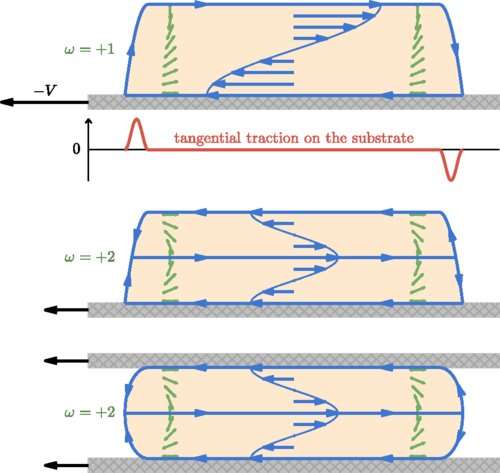

In an article published in Physical Review Letters, Bristol scientists have answered the fundamental question: “Is it possible to move without exerting force on the environment?”, by describing the tractionless self-propulsion of active matter.

Understanding how cells move autonomously is a fundamental question for both biologists and physicists.

Experiments on cell motility are commonly done by looking at the motion of a cell on a glass slide under a microscope.

“Jackson is a smart guy and probably under-appreciates that about himself,” said his dad.

He’s onto planning his next reactor using the spherical tokamak method, which traps energy differently than the reactor that he’s already built. He’s also decided that he wants to pursue nuclear physics as a career because he thinks he’ll be the one to make a fusion reactor that is actually efficient.

“He certainly has a head start,” said his dad.

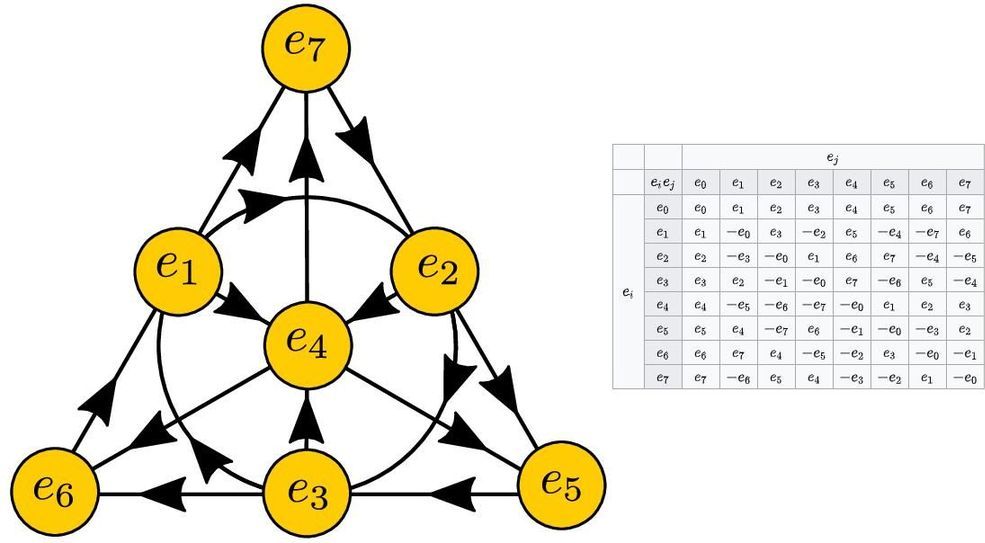

The octonions themselves will never be “the answer” to how reality works, but they do provide a powerful, generalized mathematical structure that has its own unique properties. It includes real, complex, and quaternion mathematics, but also introduces fundamentally unique mathematical properties that can be applied to physics to make novel — but speculative and hitherto unsupported — predictions.

Octonions can give us and idea of which possibilities might be compelling to look at in terms of extensions to known physics and which ones might be less interesting, but there are no concrete observables predicted by the octonions themselves. Pierre Ramond, my former professor who taught me about octonions and Lie groups in physics, was fond of saying, “octonions are to physics what the Sirens were to Ulysses.” They definitely have an allure, but if you dive in, they may drag you to a hypnotic, inescapable doom.

Their mathematical structure holds an incredible richness, but nobody knows whether that richness means anything for our Universe or not.

Astronomers discover a black hole that shouldn’t exist.

If you were to travel back in time to kill your grandparents — let’s ignore the ‘why’ here, for the sake of argument — you would never have been born. Which means there was nobody to kill your grandparents. Which means you were actually born after all, which… hold up, what’s going on here?!

These kinds of brain-breaking paradoxes have been puzzling us forever, inspiring stories ranging from “Back to the Future” to “Hot Tub Time Machine.”

Now, New Scientist reports that physicists Barak Shoshany and Jacob Hauser from the Perimeter Institute in Canada have come up with an apparent solution to these types of paradoxes that requires a very large — but not necessarily infinite — number of parallel universes.

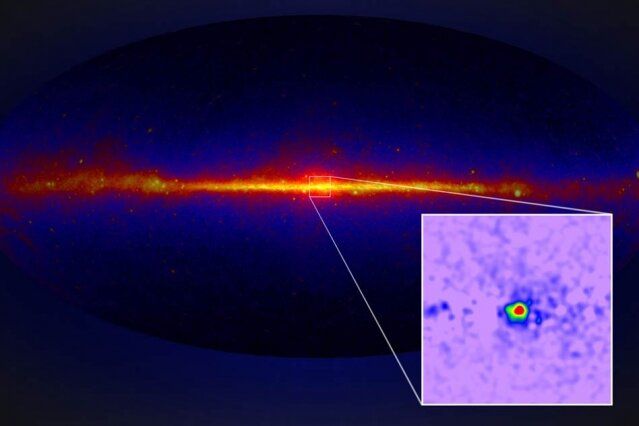

MIT physicists are reigniting the possibility, which they previously had snuffed out, that a bright burst of gamma rays at the center of our galaxy may be the result of dark matter after all.

For years, physicists have known of a mysterious surplus of energy at the Milky Way’s center, in the form of gamma rays—the most energetic waves in the electromagnetic spectrum. These rays are typically produced by the hottest, most extreme objects in the universe, such as supernovae and pulsars.

Gamma rays are found across the disk of the Milky Way, and for the most part physicists understand their sources. But there is a glow of gamma rays at the Milky Way’s center, known as the galactic center excess, or GCE, with properties that are difficult for physicists to explain given what they know about the distribution of stars and gas in the galaxy.

Abstract: In the context of warped extra-dimensional models with all fields propagating in the bulk, we address the phenomenology of a bulk scalar Higgs boson, and calculate its production cross section at the LHC as well as its tree-level effects on mediating flavor changing neutral currents. We perform the calculations based on two different approaches. First, we compute our predictions analytically by considering all the degrees of freedom emerging from the dimensional reduction (the infinite tower of Kaluza Klein modes (KK)). In the second approach, we perform our calculations numerically by considering only the effects caused by the first few KK modes, present in the 4-dimensional effective theory. In the case of a Higgs leaking far from the brane, both approaches give the same predictions as the effects of the heavier KK modes decouple. However, as the Higgs boson is pushed towards the TeV brane, the two approaches seem to be equivalent only when one includes heavier and heavier degrees of freedom (which do not seem to decouple). To reconcile these results it is necessary to introduce a type of higher derivative operator which essentially encodes the effects of integrating out the heavy KK modes and dresses the brane Higgs so that it looks just like a bulk Higgs.

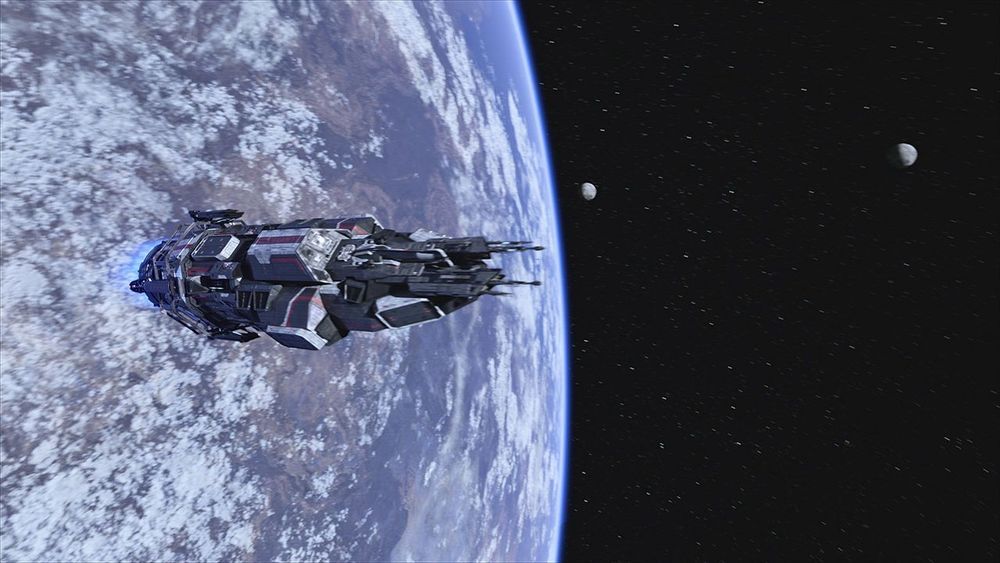

On 13 December, Amazon Prime will air the fourth season of The Expanse, a hardboiled space drama renowned for its working-class characters and real-world space physics. Showrunner Naren Shankar is part of the reason the science checks out. The veteran writer and producer for programs such as Star Trek: The Next Generation, Farscape, and the police procedural CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, has a doctorate in applied physics and electrical engineering.

Shankar chatted with about why he feels it’s important to have a realistic sci-fi show, and how television work is like the scientific peer-review process.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.