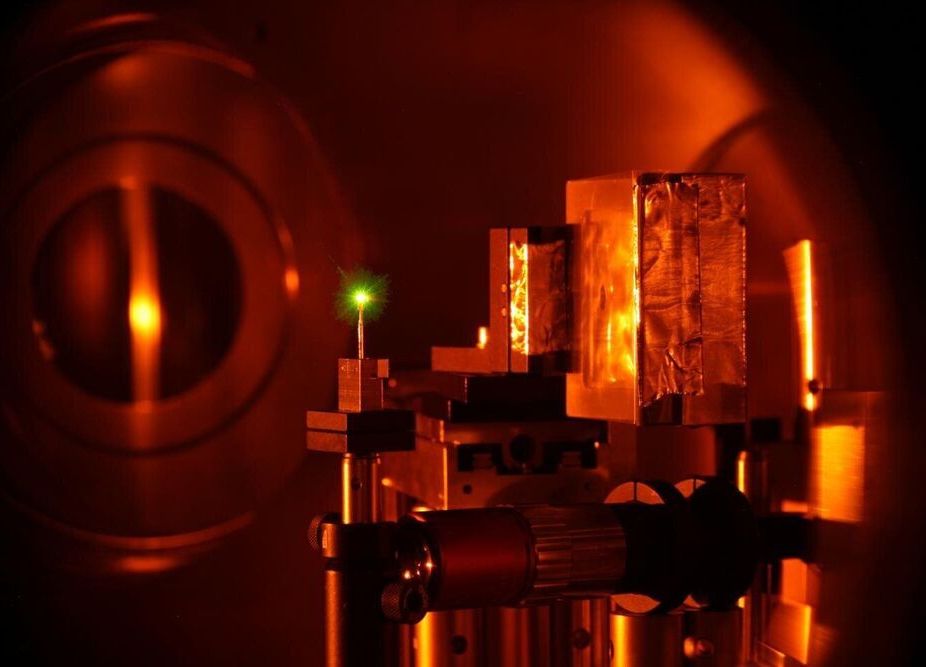

Bringing huge amounts of protons up to speed in the shortest distance in fractions of a second—that’s what laser acceleration technology, greatly improved in recent years, can do. An international research team from the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung and the Helmholtz Institute Jena, a branch of GSI, in collaboration with the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, U.S., has succeeded in using protons accelerated with the GSI high-power laser PHELIX to split other nuclei and to analyze them. The results have now been published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports and could provide new insights into astrophysical processes.

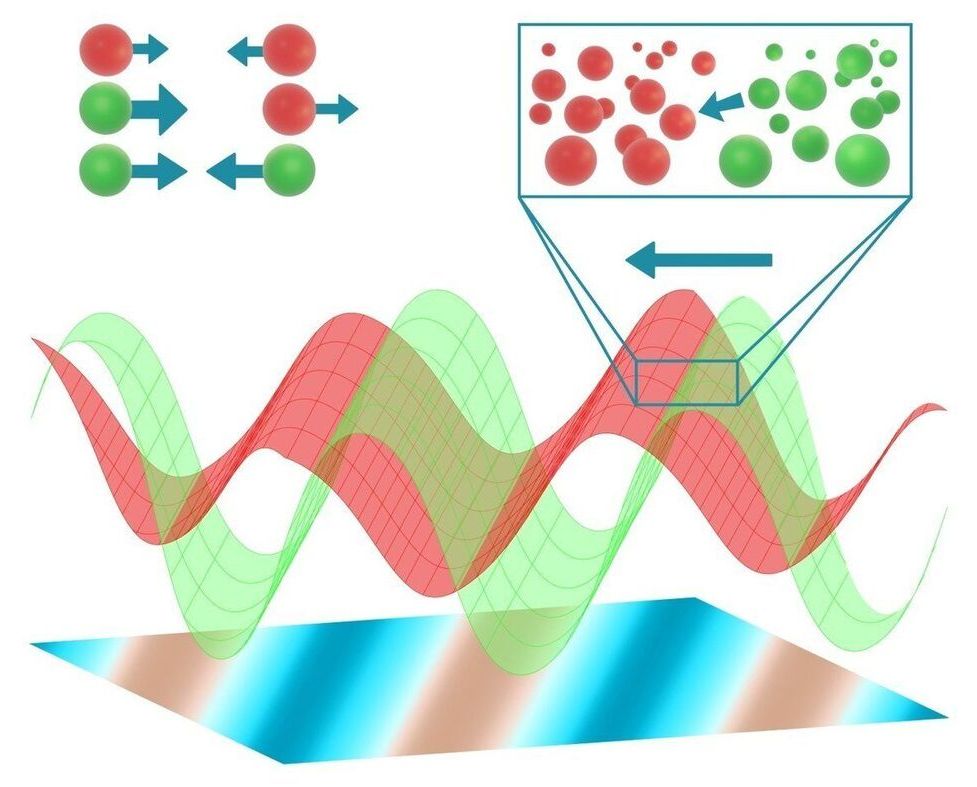

For less than one picosecond (one trillionth of a second), the PHELIX laser shines its extremely intense light pulse onto a very thin gold foil. This is enough to eject about one trillion hydrogen nuclei (protons), which are only slightly attached to the gold, from the back-surface of the foil, and accelerate them to high energies. “Such a large number of protons in such a short period of time cannot be achieved with standard acceleration techniques,” explains Pascal Boller, who is researching laser acceleration in the GSI research department Plasma Physics/PHELIX as part of his graduate studies. “With this technology, completely new research areas can be opened that were previously inaccessible.”

These include the generation of nuclear fission reactions. For this purpose, the researchers let the freshly generated fast protons impinge on uranium material samples. Uranium was chosen as a case study material because of its large reaction cross-section and the availability of published data for benchmarking purposes. The samples have to be close to the proton production to guarantee a maximum yield of reactions. The protons generated by the PHELIX laser are fast enough to induce the fission of uranium nuclei into smaller fission products, which remain then to be identified and measured. However, the laser impact has unwanted side effects: It generates a strong electromagnetic pulse and a gammy-ray flash that interfere with the sensitive measuring instruments used for this detection.