Among transhumanists, Nick Bostrom is well-known for promoting the idea of ‘existential risks’, potential harms which, were they come to pass, would annihilate the human condition altogether. Their probability may be relatively small, but the expected magnitude of their effects are so great, so Bostrom claims, that it is rational to devote some significant resources to safeguarding against them. (Indeed, there are now institutes for the study of existential risks on both sides of the Atlantic.) Moreover, because existential risks are intimately tied to the advancement of science and technology, their probability is likely to grow in the coming years.

Contrary to expectations, Bostrom is much less concerned with ecological suicide from humanity’s excessive carbon emissions than with the emergence of a superior brand of artificial intelligence – a ‘superintelligence’. This creature would be a human artefact, or at least descended from one. However, its self-programming capacity would have run amok in positive feedback, resulting in a maniacal, even self-destructive mission to rearrange the world in the image of its objectives. Such a superintelligence may appear to be quite ruthless in its dealings with humans, but that would only reflect the obstacles that we place, perhaps unwittingly, in the way of the realization of its objectives. Thus, this being would not conform to the science fiction stereotype of robots deliberately revolting against creators who are now seen as their inferiors.

I must confess that I find this conceptualisation of ‘existential risk’ rather un-transhumanist in spirit. Bostrom treats risk as a threat rather than as an opportunity. His risk horizon is precautionary rather than proactionary: He focuses on preventing the worst consequences rather than considering the prospects that are opened up by whatever radical changes might be inflicted by the superintelligence. This may be because in Bostrom’s key thought experiment, the superintelligence turns out to be the ultimate paper-clip collecting machine that ends up subsuming the entire planet to its task, destroying humanity along the way, almost as an afterthought.

But is this really a good starting point for thinking about existential risk? Much more likely than total human annihilation is that a substantial portion of humanity – but not everyone – is eliminated. (Certainly this captures the worst case scenarios surrounding climate change.) The Cold War remains the gold standard for this line of thought. In the US, the RAND Corporation’s chief analyst, Herman Kahn — the model for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove – routinely, if not casually, tossed off scenarios of how, say, a US-USSR nuclear confrontation would serve to increase the tolerance for human biological diversity, due to the resulting proliferation of genetic mutations. Put in more general terms, a severe social disruption provides a unique opportunity for pursuing ideals that might otherwise be thwarted by a ‘business as usual’ policy orientation.

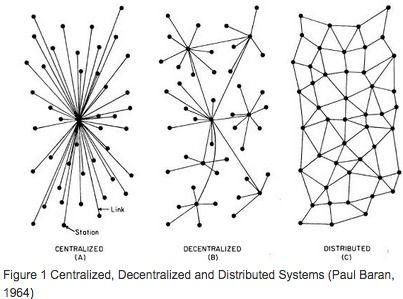

Here it is worth recalling that the Cold War succeeded on its own terms: None of the worst case scenarios were ever realized, even though many people were mentally prepared to make the most of the projected adversities. This is one way to think about how the internet itself arose, courtesy the US Defense Department’s interest in maintaining scientific communications in the face of attack. In other words, rather than trying to prevent every possible catastrophe, the way to deal with ‘unknown unknowns’ is to imagine that some of them have already come to pass and redesign the world accordingly so that you can carry on regardless. Thus, Herman Kahn’s projection of a thermonuclear future provided grounds in the 1960s for the promotion of, say, racially mixed marriages, disability-friendly environments, and the ‘do more with less’ mentality that came to characterize the ecology movement.

Kahn was a true proactionary thinker. For him, the threat of global nuclear war raised Joseph Schumpeter’s idea of ‘creative destruction’ to a higher plane, inspiring social innovations that would be otherwise difficult to achieve by conventional politics. Historians have long noted that modern warfare has promoted spikes in innovation that in times of peace are then subject to diffusion, as the relevant industries redeploy for civilian purposes. We might think of this tendency, in mechanical terms, as system ‘overdesign’ (i.e. preparing for the worst but benefitting even if the worst doesn’t happen) or, more organically, as a vaccine that converts a potential liability into an actual benefit.

In either case, existential risk is regarded in broadly positive terms, specifically as an unprecedented opportunity to extend the range of human capability, even under radically changed circumstances. This sense of ‘antifragility’, as the great ‘black swan’ detector Nicholas Taleb would put it, is the hallmark of our ‘risk intelligence’, the phrase that the British philosopher Dylan Evans has coined for a demonstrated capacity that people have to make step change improvements in their lives in the face of radical uncertainty. From this standpoint, Bostrom’s superintelligence concept severely underestimates the adaptive capacity of human intelligence.

Perhaps the best way to see just how much Bostrom shortchanges humanity is to note that his crucial thought experiment requires a strong ontological distinction between humans and superintelligent artefacts. Where are the cyborgs in this doomsday scenario? Reading Bostrom reminds me that science fiction did indeed make progress in the twentieth century, from the world of Karl Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots in 1920 to the much subtler blending of human and computer futures in the works of William Gibson and others in more recent times.

Bostrom’s superintelligence scenario began to be handled in more sophisticated fashion after the end of the First World War, popularly under the guise of ‘runaway technology’, a topic that received its canonical formulation in Langdon Winner’s 1977 Autonomous Technology: Technics out of Control, a classic in the field of science and technology of studies. Back then the main problem with superintelligent machines was that they would ‘dehumanize’ us, less because they might dominate us but more because we might become like them – perhaps because we feel that we have invested our best qualities in them, very much like Ludwig Feuerbach’s aetiology of the Judaeo-Christian God. Marxists gave the term ‘alienation’ a popular spin to capture this sentiment in the 1960s.

Nowadays, of course, matters have been complicated by the prospect of human and machine identities merging together. This goes beyond simply implanting silicon chips in one’s brain. Rather, it involves the complex migration and enhancement of human selves in cyberspace. (Sherry Turkle has been the premier ethnographer of this process in children.) That such developments are even possible points to a prospect that Bostrom refuses to consider, namely, that to be ‘human’ is to be only contingently located in the body of Homo sapiens. The name of our species – Homo sapiens – already gives away the game, because our distinguishing feature (so claimed Linnaeus) had nothing to do with our physical morphology but with the character of our minds. And might not such a ‘sapient’ mind better exist somewhere other than in the upright ape from which we have descended?

The prospects for transhumanism hang on the answer to this question. Aubrey de Grey’s indefinite life extension project is about Homo sapiens in its normal biological form. In contrast, Ray Kurzweil’s ‘singularity’ talk of uploading our consciousness into indefinitely powerful computers suggests a complete abandonment of the ordinary human body. The lesson taught by Langdon Winner’s historical account is that our primary existential risk does not come from alien annihilation but from what social psychologists call ‘adaptive preference formation’. In other words, we come to want the sort of world that we think is most likely, simply because that offers us the greatest sense of security. Thus, the history of technology is full of cases in which humans have radically changed their lives to adjust to an innovation whose benefits they reckon outweigh the costs, even when both remain fundamentally incalculable. Success in the face such ‘existential risk’ is then largely a matter of whether people – perhaps of the following generation – have made the value shifts necessary to see the changes as positive overall. But of course, it does not follow that those who fail to survive the transition or have acquired their values before this transition would draw a similar conclusion.